The huge and fast growing urban middle class of India uses a significant amount of electricity at their homes. This column argues that there is a need to focus on managing demand of electricity, and demonstrates how social norms can be used to encourage households to consume less electricity.

When we talk about energy policy in India, the conversation understandably tends to focus on a problem of supply. How do we get more energy to our rural poor and how do we do so in an affordable way? While this is certainly the major focus of energy policy in a developing country, it is worth remembering that the supply side forms only one half of an economic system. In a country with a huge and fast growing urban middle class there are over a hundred million people who use significant amounts of electricity (India Shining if you will), a number that is growing all the time. So it’s worth asking the question - Are relatively rich middle and upper-class urban Indian households using electricity efficiently at home? Should we be trying to find ways of encouraging them to use less?

Potential social benefits of reducing household electricity use

There are a number of reasons why it seems undeniable that it would be socially beneficial if large domestic consumers could be encouraged to use less – whether by engaging in energy conservation actions or by investing in more efficient appliances. Perhaps the most important involves climate change. Put simply, carbon emissions are associated with all energy consumption, these emissions lead directly to the problem of long term climate change, and yet markets and consumers do not account for these costs. The result is that every time we use energy we undercount the true social costs, and consequently we use too much. This holds true for high consuming Indians just as much as for rich Americans.

Moreover in India there are a host of other factors which also suggest that reducing electricity consumption amongst higher income urban consumers would be welfare enhancing. The first of these involves the un-priced health costs from local air pollution from both generators running on subsidised diesel and large power plants burning coal. Indeed a recent study of these air pollution costs for the United States (Muller et al 2001) suggested that many older coal power plants cause more damages to society from air pollution than benefits from the electricity they produce! Other reasons include cross-subsidies that distort demand (electricity is priced too high for industry, and too low for many domestic consumers), the absence of time of day electricity pricing, sub-optimal investment in energy efficient appliances and perhaps most importantly, the crippling electricity shortages and consequent rationing that are ubiquitous in urban India. Because electricity supply is lower than demand and the difference is met by somewhat arbitrary rationing that imposes high welfare costs on those denied power, the potential economic benefits of any reduction in demand could be very large if the electricity saved meant more was available for those with poor access.

Does demand management matter?

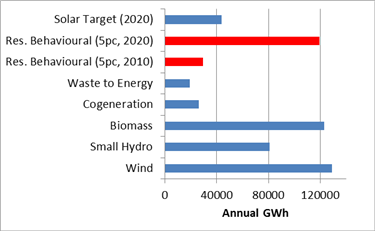

Yet even given those reasons you might well ask whether demand management even matters? After all, India produces too little energy so isn’t increasing supply what we should focus on? What would we gain from a modest reduction in demand, whether from increasing energy efficiency or changing behaviours? A good way to think about whether demand side policy is useful is to consider Figure 1. The graph simply compares the magnitude of a 5% reduction in residential electricity consumption (a modest target achievable with small efficiency improvements) to Planning Commission estimates of the total potential energy we could supply from various renewable sources. One thing seems clear - if it is worth thinking seriously about renewable energy and spending money and time improving those sources then it is also probably worth thinking just as hard about demand side policy.

Figure 1. Comparing a 5% decrease in 2010 and 2020 residential electricity consumption to Planning Commission estimates of the technological potential of various renewable energy sources

So how do we change household consumption?

Thus far I have talked only about the why of electricity demand side management. However, the problem for policy-makers is not just why but how? How do we reduce electricity consumption and encourage greater energy efficiency? Ask an economist and the answer is always the same – ‘Simple, raise the price or provide financial incentives to save’. Ask politicians, bureaucrats or utilities and the answer is normally – ‘We can’t touch the price and can’t afford financial incentives’. Now put those two together and we typically get nowhere, fast.

In recent years, behavioural economists, psychologists and cognitive scientists have argued that utilising psychological cues and behavioural techniques can be an effective way of modifying consumer actions. In other words, monetary and price incentives are one way of encouraging people to do different things but not necessarily the only way, and arguably not even always the most effective way. Certainly, monetary incentives have a lot going for them. Money is a strong motivator, well understood and carefully studied. Yet none of these facts mean that it is the only way of changing behaviour and arguably the single minded focus on price and monetary incentives in the economics literature has ignored the fact that psychologists, marketing professionals and others have been steadily refining what we know about how people respond to different psychological cues independent of money or prices. The question for policymakers is therefore – Can behavioural techniques be used the same way as monetary incentives in public policy?

Using peer comparisons

When it comes to electricity demand side management, one idea with a significant amount of promise involves the use of social norms. In simple terms, social norm theory suggests that people have a strong desire to conform to behaviour that is the norm amongst their peers. If told that we behave very differently (or worse) than others like us, we often try and adjust our behaviour to get closer to the norm. A rich literature in psychology (Schultz et al 2007) has documented the effects of social norms in different settings and an illustrative example of their effectiveness comes from their use in getting people to reuse towels in hotel rooms by simply telling them (‘Most guests reuse their towels’). This turns out to work a lot better in changing how guests behave than merely appealing to reasons such as protecting the environment by themselves or even providing additional rewards/incentives in cash or kind.

In an influential article, Allcott and Mullainathan argue that behavioural techniques have a major role to play in demand side electricity policy and can be effectively used to reduce how much people use (Allcott and Mullainathan 2010). Perhaps the best evidence of this comes from the company O-Power based in the United States. O-Power runs a set of simple behavioural interventions involving telling people whether they are consuming more than their peers (a sad face is printed on their electricity bill) or less than their peers (a happy face on the bill). This essentially zero cost program has been demonstrated to result in small but significant savings in consumption by encouraging high users of electricity to reduce consumption and encouraging low users to keep doing better than average.

Is this just something that works in one situation with very rich households in the US? Or could these ideas have value for India as well? To find out, an experiment was run with over 500 households in a residential apartment complex in Ghaziabad last year. The apartment complex in question is just one among hundreds of identical developments that are mushrooming today across the landscape of urban India. The boom in new apartment complexes forms the face of new urban housing in the country and is a major source of new electricity demand.

A very simple exercise was carried out with the local real estate developer. A randomly selected group of households were mailed report-cards every week telling them how much electricity they used vis-à-vis electricity other apartments in the complex used on average. We compared their electricity consumption over the period of the entire summer to another identical group of homes whose electricity use was monitored but who were not contacted in any way. Over a sustained period of over four months between May and September 2012 (the hottest summer in Delhi for 33 years), the group of households who received peer comparisons decreased electricity consumption by approximately 11% on average. This reduction seemed to come primarily from more careful use of air-conditioning which is the major source of energy demand in this instance (ways of reducing AC consumption include reducing hours of use, adjusting thermostats or using air coolers in dry heat). The same study attempted to measure the price elasticity1 of these households and concluded that achieving the same short-term reduction of electricity demand through price alone might require an 80% increase in price. In other words, not only did peer comparisons work but they moved the needle by a significant degree.

Looking beyond financial incentives

Governments today are framing policy to change public behaviour in many areas. These include electricity consumption, public health and education. By far the most commonly suggested policy instruments involve those that appeals to financial incentives – either through changing prices, or through conditional cash transfers. Yet while the price incentive can be a powerful one, it is worth asking whether we can be more imaginative about how to change behaviour and whether we can look to disciplines outside economics for some of the answers. For those of us worried about the environment and climate change in particular, especially given how difficult it has proved to change energy prices, it might be worth looking hard how behavioural methods based around the provision of carefully framed information might get us the motivational effects that we desire.

Notes:

- Price elasticity is the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good or service to a change in its price. More precisely, it gives the percentage change in quantity demanded in response to a one percent change in price (holding constant all the other determinants of demand, such as income)

Further Reading

- Muller, Nicolas, Mendelsohn, Robert and William Nordhaus(2011) "Environmental accounting for pollution in the United States economy", American Economic Review, 101(5):1649-1675.

- Schultz, Nolan, Cialdini, Goldstein, Griskevicius (2007) "The constructive, destructive and reconstructive power of social norms", Psychological Science, 18.pp 429-434.

- Allcott and Mullainathan (2010) "Behavior and Energy Policy", Science, 327(5970):1204-1205.

08 April, 2013

08 April, 2013

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.