Examining whether colonial history matters for women’s contemporary economic outcomes in India, this article shows that women who live in areas that were under direct British rule are better off in terms of almost all measures of women empowerment. It argues that legal and institutional changes brought in by the British in favour of women, and West-inspired social reforms in the 19th century may be relevant to explaining this long-term link.

While India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world, its female labour force participation (FLFP) rate has remained one of the lowest. According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey 2021-22, only around 29% of women in the age group 15 to 59 were a part of the labour force. This sharply contrasts with the labour force participation rate of men, which is close to 81% - comparable to that of developed countries. In terms of other measures of female empowerment as well, India's performance has been less than satisfactory – as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2015-16, close to 50% of women reported that they lack financial autonomy and agency within the household.

While these averages present a grim picture, they mask a lot of regional heterogeneity. States like Himachal Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu have much higher FLFP as compared to the average, whereas states like Bihar, Haryana and Punjab are much below the average. This heterogeneity is observed at the district level as well, where districts like Samastipur and Begusarai in Bihar have abysmally low FLFP (around 1%), while Mandi in Himachal Pradesh has FLFP rates comparable to males (around 70%).

In a recent paper (Nandwani and Roychowdhury 2023), we explore whether historical factors can help explain some of this heterogeneity. In particular, we investigate the role of India's colonial history, dating back to the 18th and 19th century, in explaining today's heterogeneity in women’s employment and other measures of women’s empowerment.

British India and the princely states

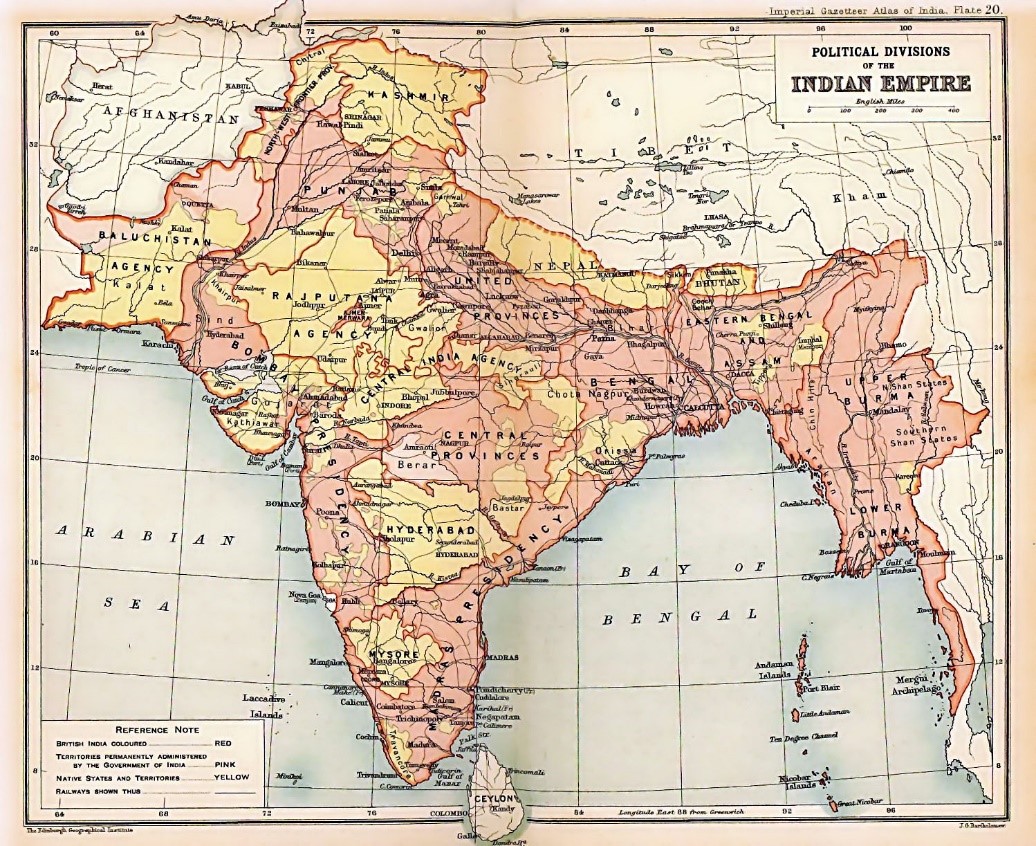

India was a British colony for close to two centuries – the East India Company ruled over the Indian subcontinent from 1757 to 1856, and the British crown took over the administration from 1858 to 1947, after which India became an independent nation. However, the entire country was not under direct British rule: while 60-65% of the present-day districts were under direct control of the British (hereafter referred to as 'British India'), the remaining comprised of several 'princely states' – political communities which had their own legal, political and administrative structure, and were ruled by hereditary kings. The East India Company started its conquest of these princely states in 1757, but did not annex all the regions in the country primarily because it was not numerically and politically strong enough to administer the entire subcontinent. This continued till 1857, when the crown took over the administration and East India Company stopped further annexation. Thus, within the same country, there were territories that came under direct control of the British rule, and colonial laws were applicable in these areas. The princely states, on the other hand, enjoyed relative legal, political and administrative autonomy.1

Figure 1. British Indian districts and princely states within the Indian Empire.

In addition to the way these regions were governed, British India significantly differed from princely states along institutional and administrative lines. We examine if these differences have long-term implications on several contemporary outcomes for Indian women.

Empirical strategy

Investigating the causal link between British colonialism and contemporary outcomes of women is not straightforward. Existing work (Iyer 2010, Roy 2020) shows that the East India Company prioritised agriculturally productive regions for annexation. There is also growing evidence that agriculturally fertile regions have different gender norms and attitudes towards women empowerment as compared to other regions (Alesina et al. 2013, Hansen et al. 2015). We therefore use an instrumental variable methodology2 to address this identification issue. In particular, following Iyer (2010), we use the doctrine of lapse policy of annexation as an instrument for British colonisation. This notorious policy was introduced by Lord Dalhousie, the Governor General of India between 1848 and 1856, and stated that if the ruler of a princely state died without any natural heir (adopted children were not recognised as legal heirs), the princely state would cease to be under the rule of the local king and come under British rule. The identifying assumption here is that the death of a ruler without a natural heir in the specific period 1848 to 1856 is likely to be a matter of circumstance, rather than caused by systemic factors that might also affect women's long-term outcomes.

We use rich historical data collected by Iyer (2010) that provides information on the regime under which the districts historically were, mode of annexation, year of annexation, etc. for 417 Indian districts (as per the 1991 Census). We extend this data for to 2011 Census districts, and merge it with NFHS 2015-16 and National Sample Survey (NSS) 2011-12 to create two analytical samples.

Key findings

Our empirical results suggest that women are more economically empowered in districts that were historically under direct British rule. Compared to their counterparts, women who live in districts that were directly ruled by the British are 2 percentage points and 4 percentage points more likely to be employed as wage and casual labourers, respectively. Quantitatively, this amounts to 50 and 57% higher likelihood than the present national average.3

Additionally, women in former British districts are 6.6 percentage points more likely to be allowed to go to the market alone and 8 percentage points more likely to be allowed to go somewhere outside the village alone. These represent a 10 to 15% increase as compared to the average. Women in erstwhile British Indian districts are also 6 percentage points more likely to have financial autonomy – a 10% increase as compared to the national average. Women in British ruled districts are 6 percentage points less likely to face less severe intimate partner violence, and 3 percentage points less likely to face sexual violence. We also find that women in areas colonised by the British are more educated (6 percentage points more likely to be literate, and have 0.5 more years of schooling on average), were married at an older age, have lower actual fertility, follow better gender norms regarding intra-household decision making, and are married to men who are more likely to be literate and have more progressive attitude. These findings suggest persistent gendered effects of colonisation.

Why does colonial history matter?

Although data availability limits the detailed examination of the possible reasons why colonial history translates into increased empowerment, we consider a few possible channels and provide suggestive evidence on their plausibility. Our analysis allows us to rule out several channels including investment in women’s education by the British, difference in the extent of catholic and protestant missionary activities between British India and princely states, investment in railways by the British, and participation of women in politics. The channels that we cannot rule out are legal changes brought in by the British in favour of women, and the West-inspired social reformation movement of the 19th century.

i) Legal changes: The British enacted a series of legal changes that claimed to liberalise women's position in society. This was partially a result of the long-standing demand of Indian social reformers, who considered traditional Hindu practices like Sati (widow-burning) and child marriage to be archaic and detrimental to the status of women. British administrators also believed that some of the cultural practices were severely discriminatory, and so, between 1795 and 1937, they liberalised the laws on six major issues of relevance to women. In particular, Sati was prohibited; widow remarriage was allowed; the age of consent to sexual intercourse was fixed at 10, and then raised to 12; female infanticide was prohibited; child marriage was forbidden; and several laws improving women's inheritance rights were passed. These legal changes were only applicable to areas that were under direct colonial rule, while princely states continued with the traditional cultural practices of Sati and child marriage, among others. Our empirical analysis suggests that progressive legislations brought in by the British and institutional changes could be a mechanism driving our main results.

ii) Reformation movements: Indian society in the 18th century was mired with superstitions, archaic traditions and social evils, often meted out to women. However, the spread of education, particularly science and math, and increased exposure to western philosophies in British India in the early 19th century led to an awakening of educated Indian elites who recognised the need for reforms in Indian society (Rai 1979). British India thus witnessed the rise of several social reformers and reform movements in the 19th century. Even though the movements differed somewhat in their ideologies, a common theme that tied them was their pursuit of gender reforms.

Thus, while the British did not invest in education of women, the active presence of social reform movements and enactment of progressive legal reforms, incidental to British colonial rule, could have improved social norms regarding the socioeconomic status of women, thus resulting in a long-term improvement in outcomes.

Concluding remarks

Although, our results of positive impact on women empowerment might seem surprising, particularly given that existing work has highlighted lower provision of public services and slower economic growth in British Indian districts (see, for instance, Iyer (2010) and Jha and Talathi (2023)), they are in line with Roy and Tam (2022) and Guarnieri and Rainer (2021) who, in the context of India and Cameroon respectively, document that British colonisation had positive long-term effects on women’s outcomes.

Gender equality and providing women with opportunities to work outside the spheres of their homes have been identified as important Sustainable Development Goals that the United Nations member countries have aimed to achieve by 2030. Unfortunately, however, gender inequality is pervasive in many parts of the world, and women continue to face constraints to their socioeconomic participation in society. Our findings highlight the importance of understanding a community’s social background and historical factors when formulating policies to address gender inequality. Further, they suggest that progressive legal reforms that aim to alter social or gender norms can have intergenerational beneficial effects on women's lives.

Notes:

- However, defense and foreign policy were still controlled by the British.

- Instrumental variables are used in empirical analysis to address endogeneity concerns. The instrument is correlated with the explanatory factor (that is, British rule in a territory) but does not directly affect the outcome of interest (women’s empowerment), and thus can be used to measure the true causal relationship between the explanatory factor and the outcome of interest.

- The FLFP rate for NSS 2011-12 is 25%. However, the average probabilities for women of employment as wage and casual labourers are 4% and 7% respectively.

Further Reading

- Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano and Nathan Nunn (2013), "On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2): 469-530.

- Guarnieri, Eleonora and Helmut Rainer (2021), "Colonialism and female empowerment: A two-sided legacy", Journal of Development Economics, 151: 102666.

- Hansen, Casper Worm, Peter Sandholt Jensen and Christian Volmar Skovsgaard (2015), "Modern gender roles and agricultural history: the Neolithic inheritance", Journal of Economic Growth, 20: 365-404.

- Iyer, Lakshmi (2010), "Direct versus indirect colonial rule in India: Long-term consequences", The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4): 693-713. Available here.

- Jha, Priyaranjan and Karan Talathi (2023), “Impact of Colonial Institutions on Economic Growth and Development in India: Evidence from Night Lights Data”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming. Available here.

- Nandwani, B and P Roychowdhury (2023), ‘British Colonialism and Women Empowerment in India’, Working Paper. Available here.

- Rai, Kauleshwar (1979), "BRITISH ATTITUDE TOWARDS SOCIAL REFORMS IN MODERN INDIA", Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 40: 904-907.

- Roy, T (2020), The Economic History of India 1857-2010, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

- Roy, S, and EHF Tam (2022), ‘Impact of British Colonial Gender Reform on Early Female Marriages and Gender Gap in Education: Evidence from Child Marriage Abolition Act, 1929’. Available here.

22 June, 2023

22 June, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.