Declining female workforce participation in India is a matter of grave concern, and a puzzle in the face of increased overall economic growth. This column shows that although the proportion of working women – based on estimates from the National Sample Survey - has fallen, there is improvement in terms of the number of days of work by women in the workforce, especially in rural areas.

Tweet using #womenandwork

The statistical measure used to look at the declining trend in workforce participation rates (WPR) is the ‘usual status’1(comprising workers in their principal and subsidiary status) WPR estimated from the National Sample Survey (NSS) or comparable figures from the population census. This measure gives the number of women usually engaged in economic activities during a year as a percentage of total women, without taking into consideration the intensity of work in terms of number of days actually worked. However, the WPR following the daily-status approach is considered a more inclusive concept as it is estimated in terms of person-days (or half days) worked in relation to the number of days the person is available for work2. The difference between these two measures can thus be taken as an indicator of the underutilisation of labour time of those working.

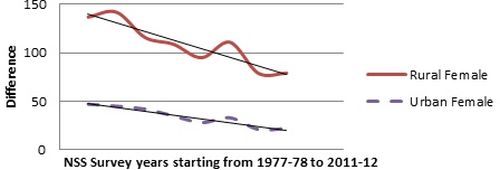

Figure 1 below shows the differences between female WPR by these two alternate concepts for rural and urban areas, for the period between 1977-78 and 2011-12. The differences in the two rates for rural women turn out to be very high vis-à-vis urban women. The narrowing of the difference between the usual-status and daily-status rates is noteworthy. It is thus possible to argue that the volume of work available, measured by the number of half days, has gone up for the usual-status workers, particularly for rural women. This implies that the decline in usual-status WPR is partially compensated by the increased volume of work for those counted as usual-status workers.

Figure 1. Absolute difference between usual-status and daily-status WPR for rural and urban women

Note: The survey years considered are 1977-78, 1983, 1987-88, 1993-94, 1999-00, 2004-05, 2009-10, and 2011-12 corresponding to the NSS large sample surveys on employment–unemployment.

Note: The survey years considered are 1977-78, 1983, 1987-88, 1993-94, 1999-00, 2004-05, 2009-10, and 2011-12 corresponding to the NSS large sample surveys on employment–unemployment. Disaggregating rural women workforce

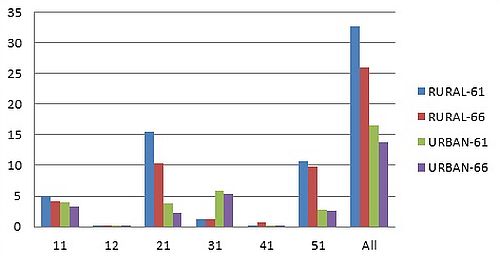

The decline in WPR for rural women can also be analysed by disaggregating the total employment into a number of categories. Figure 2 below gives the percentage of different types of usual-status workers in the total female population, along with the total female WPR. It may be noted that there has been a fall in all these categories except the casual workers. In case of casual workers, the increase is due to their reporting for ‘public works’, mostly under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)3. The category for which WPR has declined substantially is that of unpaid family workers (status code 21). The percentage of women reported as unpaid family workers in rural areas was as high as 15.6% in 2004-05, which has gone down to 10.3% in 2011-12. This, however, may not be considered an undesirable shift. Besides this, increased number of working days would also mean that they are no more required to assist the family enterprises either due to improved income or because the family enterprises are on a decline.

Figure 2. Percentage of female workers in different types of worker categories from NSS 61st and 66th rounds

Note: Codes on horizontal axis stand for - 11: Own account workers, 12: Employers, 21: Unpaid family workers, 31: Regular salaried workers, 41: Causal work in public works, and 51: Casual work in others.

Note: Codes on horizontal axis stand for - 11: Own account workers, 12: Employers, 21: Unpaid family workers, 31: Regular salaried workers, 41: Causal work in public works, and 51: Casual work in others. Women’s participation in public works

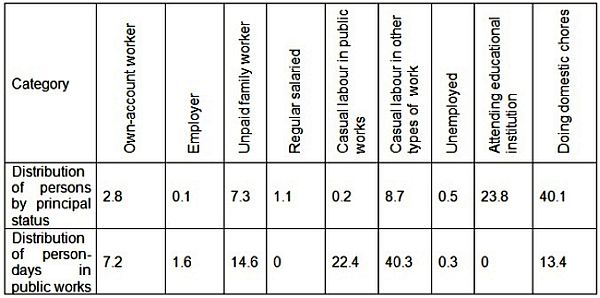

In order to assess the impact of public works programmes in the rural labour market, persons have been placed in different categories based on their engagement by principal status. The second row of Table 1 below gives the distribution of the total number of days reported under public works (expected to be mostly in MNREGA) according to the principal-status categories of the persons reporting public works.

Table 1. Distribution of persons and person-days in public works according to the principal status for rural women: NSS 66th round (2009-10)

Note: Children below five years of age, pensioners, etc. are excluded; hence, row values do not add up to 100.

Note: Children below five years of age, pensioners, etc. are excluded; hence, row values do not add up to 100.

Nine per cent of women who are in casual employment claim about 63% of the public works of women. One would have expected this percentage to be even higher since public works programmes are meant mostly for casual labourers. Among women, the share in public works is as high as 14.6% for unpaid family workers; 13.4% for those engaged in domestic chores; and 7.2% for own-account workers. Thus, in the case of females, about 28% of the person-days are availed by those who are otherwise engaged in domestic duties or family enterprises as unpaid workers. This shift in the nature of engagement of women and the structure of the workforce, as a result of public works programmes, ought to be seen as a positive development in the rural labour market and would, to an extent, explain the decreased usual-status WPR.

Concluding remarks

These findings imply that although WPR according to usual status has been declining over the years, the actual number of days worked by usual-status female workers has not declined proportionately. The decline in female WPR is mainly due to the lower percentage of females reporting as unpaid family workers, many of whom are finding work in MNREGA. The participation of housewives in MNREGA is also not reflected in the usual-status WPR.

Notes:

- An individual is defined as being employed according to principal status, if they engage in the NSS definition of economic activity for a majority of the year. An individual is defined as being employed according to subsidiary status if they engaged in an economic activity for at least 30 days in the 365 days preceding the survey.

- In a population where workers are employed full-time and the unemployed do not work at all, the usual status rate will converge with the daily status WPR. The usual status rate would generally be higher than that by daily status because of underemployment among the subsidiary and even principal status workers in self-employment or casual work.

- The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA), 2006 guarantees 100 days of employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at the minimum wage.

14 July, 2017

14 July, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.