In May 2016, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code law was passed by Indian Parliament and received presidential assent. The law consists of provisions for both corporate and personal insolvency. However, only the corporate insolvency provisions are being implemented. In this article, Sane and Sharma focus on personal credit extended by banks with a view to informing policy actions on personal insolvency provisions of the Code.

In May 2016, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) law was passed by Parliament and received presidential assent. The law consists of provisions for both corporate and personal insolvency. However, only the corporate insolvency provisions have been notified and are being implemented. The rapid implementation of the corporate insolvency provisions is largely a response to the policy discourse on the non-performing asset (NPA) problem of the banking sector.

In this article, we turn our attention to personal credit extended by banks, with a view to informing policy actions on the personal insolvency provisions of the IBC. While banks are just one source of personal credit amidst a variety of institutional and non-institutional sources, they are the largest ‘formal’ source of credit, and therefore, the first likely users of the insolvency provisions. Understanding the nature and composition of personal credit extended by banks has implications for effectively designing the procedural aspects of insolvency resolution under the Code, as well as the institutions that enable the resolution. The decisions surrounding personal insolvency can help lay the foundation for a healthy market for individual credit.

Bank credit to the household sector

We use data from the ‘Quarterly BSR-1: Outstanding Credit of Scheduled Commercial Banks’ released by the RBI (Reserve Bank of India). This is a quarterly data series, from March 2014 till September 2016, which provides the composition of bank lending by organisation, occupation, loan size, interest rate bands, and regions. RBI classifies household (HH) sector credit into three categories: (i) individual borrowers; (ii) proprietary concerns, joint families and unregistered partnerships; and (iii) joint liability groups (JLG), NGOs (non-governmental organisations) and trusts. The data give us the following information on the size and composition of lending to this sector:

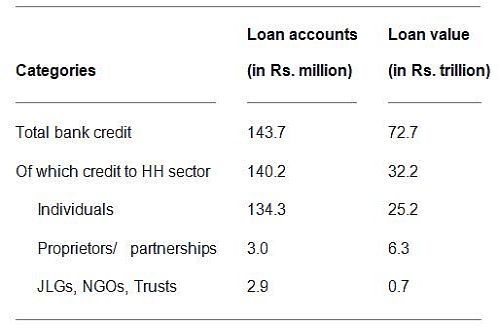

- HH sector credit is large, both in terms of value and accounts: In September 2016, credit to the HH sector was Rs. 32.2 trillion, 44.3% of the total credit given by banks. In terms of number of loan accounts, HH sector accounted for 98% of the total accounts in the banking system (Table 1). Within the HH sector, credit to single individual borrowers was the largest component, both in terms of value and number of accounts.

Table 1. Household sector credit in India

- Bank credit to HH sector is growing at a faster rate than credit to the corporate sector: Between Q1 2015 and Q2 2016, bank credit to the HH sector has seen an average quarter-on-quarter (Q-o-Q) growth of 3%. By contrast, in the same period, bank credit to non-HH sectors has only seen an average Q-o-Q growth of 0.3%.

- Bulk of HH sector credit is given as agricultural and personal loans: Personal loans (mostly in the form of secured housing and vehicle loans for which collateral is given) and agricultural loans account for Rs. 22 trillion or 67% of the total bank credit to the HH sector. Average loan sizes are relatively small: Rs. 120,000 per loan for agriculture, and Rs. 260,000 per loan for personal loans.

The remaining 33% are business loans spread mainly across three sectors: industries (12%), trade and transport (13%), and professional services (6%). Within industries, most loans are given to proprietors and partnerships, and at an average size of Rs. 930,000, these are relatively large. In trade, transport and services, average loan size is between Rs. 350,000 to Rs. 500,000 per loan.

- Southern and western regions account for more than 60% of agricultural and personal loans, by value and by accounts: Around 38% of total value of agricultural and personal loans, and 46% of the loan accounts, are in the southern region. The corresponding figures for the western region are 24% and 19%, respectively. Two states - Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra - account for 30% of the total loan value and 40% of the loan accounts.

- Agricultural loans are given mainly in rural and semi-urban centres while personal loans are given mainly in urban and metropolitan centres: Around 85% of agricultural loan accounts and 72% of the total loan value are given in rural and semi-urban centres. These are places with population less than 0.1 million. In case of personal loans, 58% of loan accounts and 51% of total loan value are given in metropolitan areas. These are centres with population of 1 million or more.

- Agricultural credit is largely short tenure whereas personal loans are medium to long tenure: 70% of agricultural credit is given in the form of cash credit or as demand loans. In contrast, more than 80% of personal loans are medium- to long-tenure loans.

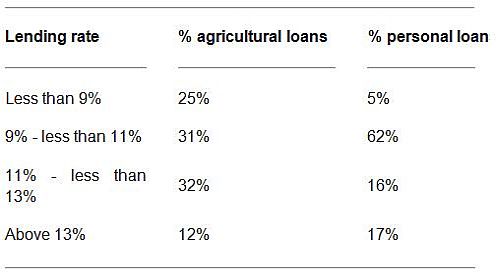

- Distribution of loans across agricultural and personal categories by interest rate ranges, suggests that, at an aggregate level, there is limited margin for NPAs: Table 2 shows the distribution of loans across agricultural and personal categories by interest rate ranges. A comparison of the lending rates with the marginal cost of lending rate (MCLR) for State Bank of India (SBI) from September 2016 shows that the margin available for NPAs is limited. The short term MCLR, relevant for agricultural loans, is 9.05%. Around 56% of agricultural loans, are in the 6-11% lending rate category, suggesting a less than 2% room for NPAs. Similarly, the MCLR relevant for personal loans is 9.25%. 67% of personal loans are in the 6-11% lending rate category, suggesting less than 1.75% room for NPAs.

Table 2. Distribution of loans across agricultural and personal categories by interest rate ranges

- Banks have limited mechanisms for enforcement: Currently, banks can avail of SARFAESI1(The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002) for resolving secured loans. However, for individual debtors it is used more as a deterrent than an actual enforcement mechanism. Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), with their threshold of Rs. 1 million, are available only to the 6-7% of personal credit loan accounts which meet the threshold. For the remaining segments of personal credit, the only mechanism available is the slow and costly civil court system. Some banks use the provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 for recovery. However, the enforcement of arbitration awards relies on the civil court system. There is no collective resolution process available to deal with an individual with a portfolio of loans. Each lender has to pursue its recovery action separately. This proves to be inefficient and costly.

Implications for IBC implementation

The size and nature of personal credit extended by banks has the following implications:

Design of IBC resolution procedures:

Most personal loans are secured loans, and banks might continue to use SARFAESI for recovery action on them. IBC may be used mostly in cases where a debtor has multiple unsecured loans, or where the debtor wishes to file for protection under the Code.

A large proportion of agricultural loans are given to low-income households. It is possible that many of them will qualify for the ‘fresh start’2. As most of these loans are in rural and semi-urban areas, design of access will be important for these households to be able to apply for such a waiver.

For those loans that do come to the IBC, the Insolvency Resolution Process (IRP) needs to be aligned with the borrowers´ profile. A resolution procedure for an individual borrower with low-value loans needs to be simple, low cost and time efficient. A simple form-based resolution mechanism, that requires little or no adjudication, may be desirable here. In contrast, resolution procedure for a large borrower or a proprietor may be closer in design to the process for a small company.

Reach, procedure, cost structure and role of the DRTs:

The size of the loans, their complexity, and their geographical spread will need to shape resourcing decisions of the DRTs. This will, in turn, decide their effectiveness as the adjudicating authority for personal insolvency cases. Today DRTs are designed to deal with bank loans above Rs. 1 million. There are only 6.5 million loan accounts in this size threshold in the entire banking system. In contrast, there are 140 million HH loan accounts, and their average size is Rs. 230,000. To effectively deal with resolution of such loans, the DRT rules of procedure, reach, infrastructure, as well as their use of technology for case management, will require a comprehensive rethink.

How the market for resolution professionals (RPs) may develop:

The role of RPs (the intermediaries defined under the IBC), as well as how the RP profession evolves for personal insolvency cases, will be critical. It is likely that, for high-value loans, a market for private RPs, concentrated in urban and metropolitan centres, will develop organically. However, for small-sized loans, which are geographically dispersed, the question of who will be the RPs and what role they will perform will require assessment, and perhaps even policy action. Further, even when RPs are identified, the process for their licensing, training and monitoring will need to be carefully formulated.

Design, accessibility and cost structures of Information Utilities (IUs):

The institution of information utilities (IUs) is a core component of IBC design. The IUs are expected to facilitate the digitisation of credit transactions, and give such digital records sanctity as evidence in courts of law. Information in an IU can be used for establishing default, and initiating insolvency resolution processes. The structure of IUs, their mechanisms for accepting personal credit related information, and their standards of service will need to be aligned with the need to digitise a large number of small-value loan accounts given to individuals.

Role of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI):

For personal insolvency, one of the biggest challenges for the IBBI will be dealing with consumer protection issues. Individual debtors will be vulnerable to biased advice on whether to file for insolvency, the process guiding the filing, and the process for resolution. The IBBI will have to step up to the challenge of protecting customer interests from misaligned incentives that stem from high-powered sales practices that have plagued other sectors of the retail financial market.

Conclusion

The design of personal insolvency systems is a complex problem, with challenges that are completely different from those faced by corporate insolvency systems. In this article, we have discussed only the market for bank credit. There will be a larger category of lenders, including money-lenders and friends and family, that may at some point wish to use the provisions under the IBC. Given the size and complexity of the personal credit market, and the paucity of effective recovery mechanisms, there is need for carefully planning and implementing the personal insolvency law sections of the IBC. This is unlike the approach followed for implementing corporate insolvency provisions where speed of implementation has been prioritised.

A version of this article has previously appeared on Ajay Shah’s blog: https://ajayshahblog.blogspot.in/2017/03/the-size-of-personal-bank-credit-in.html.

Notes:

- Under the provisions of the SARFAESI Act, a secured creditor has the right to enforce security interest (that is, legal claim on collateral that has been pledged) if the loan is classified as an NPA in accordance with guidelines issued by the RBI. The Act aimed to establish a separate mechanism for debt recovery to enable financial institutions to recover their NPAs and enforce security without the intervention of the courts.

- Fresh start is a process under the IBC which allows for a debt waiver for individuals below some income and asset thresholds. There is a danger in India that politically motivated loan-waivers destroy the credit culture. A smooth process of dealing with insolvent poor people, which works every day, could potentially de-politicise the problem.

Further Reading

- Ministry of Law and Justice (2016), ‘The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016’, The Gazette of India, 28 May 2016.

- Ministry of Corporate Affairs (2017), ‘Report of the Working Group on Information Utilities’, Government of India.

- Sane, R (2013), ‘Mis-selling: from impressions to evidence’, Ajay Shah’s blog, 30 April 2013.

- Sane, R and S Garg (2015), ‘Treatment of individual credit in the draft Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code’, Ajay Shah’s blog, 5 December 2015.

10 May, 2017

10 May, 2017

By: Consumer Debt Counselors 05 August, 2022

Nice content