The recommendations of the recently constituted Sixteenth Finance Commission (FC16) will govern the sharing of revenues between the Union and states during 2026-2031. In this post, Ganguli and Sinha look back on the Fifteenth Finance Commission (FC15) Report, in the context of the mandate to address vertical and horizontal imbalances in fiscal federalism. In their view, FC16 should focus on regional disparities and seek to promote equity and efficiency.

The sharing of financial powers between the Union and states in a federation has always been debatable. As per the Wicksellian Connection1 there is a genuine link between revenue raising and expenditure decisions, which leads to efficiency and accountability (Bird and Slack 2014). Thus, the transfers should not only correct the fiscal mismatch between the revenue sources and expenditure needs of the states, but should also reduce the possible inequalities in their revenue capacities and costs of providing public goods and services (Sarma 1997). However, the issue of formulating an appropriate mechanism aiming at reduction of fiscal imbalances both vertically (between the Union and states) and horizontally (among states), remains controversial. In numerous cases, the determination of criteria is guided by political dominance rather than economic rationale.

In India, fiscal transfer is a quinquennial ritual undertaken by successive Finance Commissions (FC) constituted for the purpose (Sarma 1997). The FC lays down the principles for giving recommendations on (i) the distribution of a divisible pool of taxes between the Union and the states; (ii) fixing of inter-se shares; (iii) principles which should govern the grants-in-aid; and (iv) augmenting the Consolidated Fund of a state to supplement the resources of local bodies. In addition, any other matter can be referred to the Commission in the interest of ensuring sound state finances.

The Fifteenth Finance Commission (FC15) Report, which was tabled on 1 February 2021, had the enormous task of maintaining fiscal harmony given the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, the Commission had too many boxes to tick. The Sixteenth Finance Commission (FC16) was constituted in December 2023, to cover a period of five years starting 1 April, 2026. Its Terms of Reference (ToR) is a heavily debated issue between the Centre and states.

The objective of this post is to critically review the commitments of FC15 under the Constitution, and note how FC16 should be mindful of regional disparities and emphasise equality, equity and efficiency while framing the report.

Vertical imbalance: Rising cess and surcharge

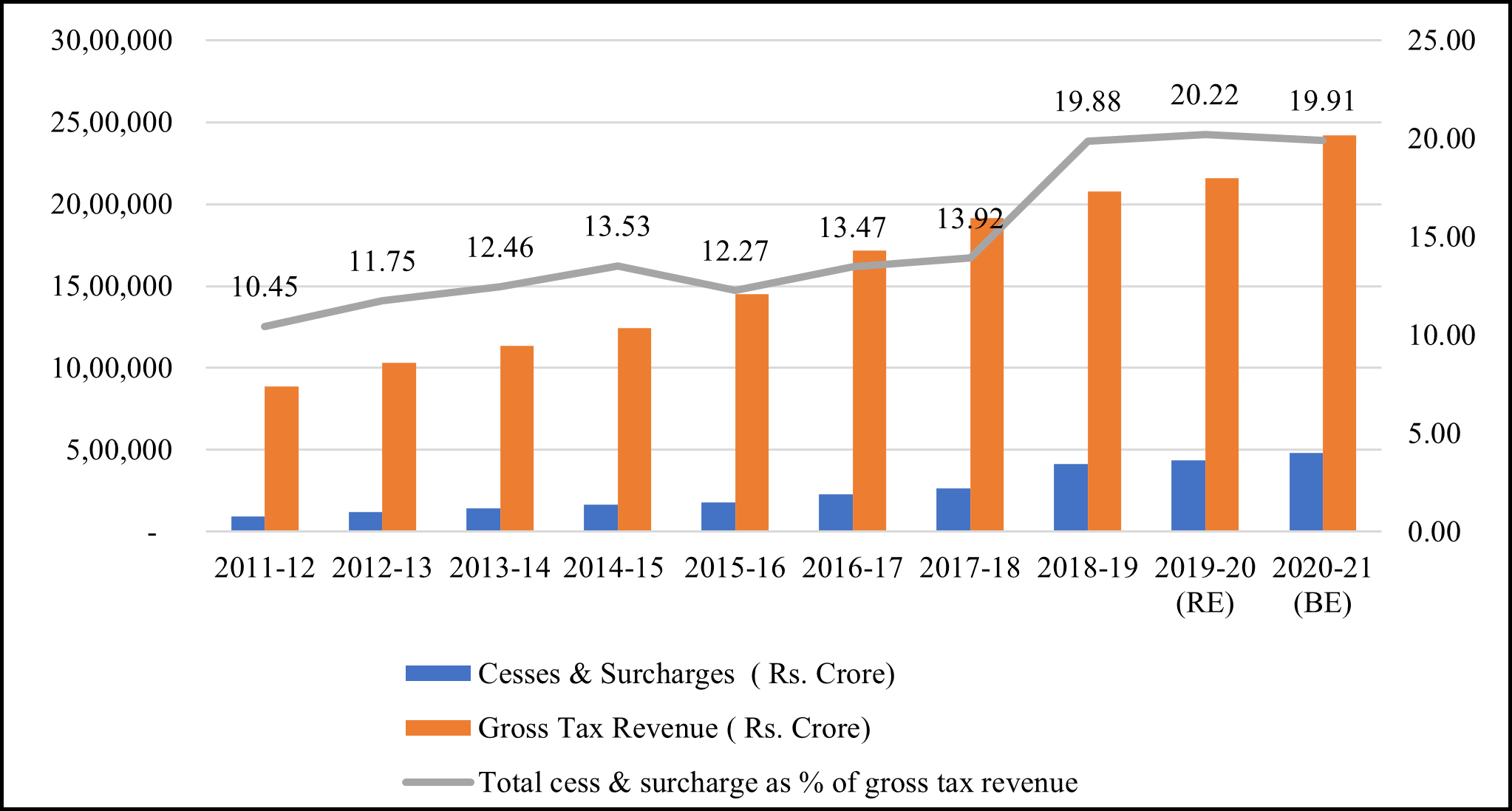

The distribution of power between the Centre and states as put forth by the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution has created a fiscal gap, and led to a vertical fiscal imbalance. As per this financial relation, greater revenue-raising powers are with the Union, whereas much of the expenditure responsibilities, mainly those pertaining to welfare and development, are with the states (Sharma et al. 2021). As per the FC15 Report, the states had only 37.3% of the resources but were responsible for 62.4% of the incurred expenditure. This reflects the large vertical imbalances arising between the Union and the states due to effective commitment of expenditure compared to the revenue powers (Mohan 2020). While the mandate of the FC is to bridge this gap, gradual increases in cess and surcharge2 are causing the divisible pool to shrink (Figure 1) as these are not shareable with the states (Kotha et al. 2018). This may be inferred from the fact that the growth in grants-in-aid to states are higher than the tax devolution to the states.

Figure 1. Share of cess and surcharges in gross tax revenue

Notes: i) In the last four years, starting from 2017-18, the share of cess and surcharge also includes Goods and Service Tax (GST) compensation of 3.3%, 4.6%, 4.5% and 4.6% respectively. ii) The data for 2019-20 and 2020-21 come from revised estimates (RE) and budget estimates (BE) respectively.

Source: FC15 Report & Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

The figure above shows that between FY2011-12 and FY2019-20, the cess and surcharges increased by 4.7 times, from Rs. 92,537 crore to Rs. 436,809 crore. With this increase, cess and surcharges as a part of gross tax revenue increased from 10.5% in FY2011-12 to 20.2% in FY2019-20 (RE).

Horizontal imbalance and increasing disparity among states

The FC is constituted to look into issues in the implementation of fiscal federalism policies. Its emphasis is on assessing and correcting both the vertical and horizontal imbalances in this regard. Despite good intentions and thorough analyses of fiscal scenarios, often the relatively weaker states find themselves discriminated against (Das and Mishra 2008). As per Buchanan (1950), states vary in terms of fiscal capacity, with low-income states facing greater fiscal pressure than high-income states. However, broad compliance with the universal applicability of the criteria originally suggested by FCs (detailed in Table 1 below) in the past undermines these differences among states. For instance, for a state such as Bihar, the selection of criteria like 2011 population and ‘income distance’ are desirable steps. However, indicators like demographic performance (12.5%), area (15%), forest and ecology (10%) and tax effort (2.5%), add up to a deficit of 40%- of the qualifying criteria for Bihar.

Table 1. Criteria and weights assigned by different FCs (in %)

|

Criteria |

FC12 |

FC13 |

FC14 |

FC15 |

|

Need-based indicators |

||||

|

Population 1971 |

25 |

25 |

17.5 |

- |

|

Population 2011 |

- |

- |

- |

15 |

|

Demographic Change |

|

10 |

|

|

|

Demographic performance |

|

|

|

12.5 |

|

Cost disability indicator |

||||

|

Area |

10 |

10 |

15 |

15 |

|

Revenue disability indicator |

||||

|

Income distance |

50 |

|

50 |

45 |

|

Fiscal capacity distance |

|

47.5 |

|

|

|

Forest cover |

7.5 |

|

||

|

Forest and ecology |

|

|

|

10 |

|

Fiscal efficiency indicators |

||||

|

Fiscal discipline |

7.5 |

17.5 |

||

|

Tax effort |

7.5 |

|

||

|

Tax and fiscal efforts |

|

|

|

2.5 |

It is evident from the economic theory of backward economies that population growth is a common phenomenon in less developed regions. It should be noted that an increase in population of any backward state is not a wilful choice. Rather, this is among the basic characteristics of a weak economy in most of backward regions (Ganguli and Sinha 2020). Thus, while selecting criteria, the needs of all states must be taken into consideration, especially underdeveloped states like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, etc. However, in contrast to adopting a need-based approach, the previous Commissions have followed almost the same old pattern. Table 1 shows the criteria and weights adopted by previous Commissions; while Table 2 shows the share in net tax proceeds of some major Indian states.

Table 2. Share of major Indian states in net tax proceeds (in %)

|

State |

Per capita income (in FY2011-12 rupees) (2020-21) |

FC12 (2005-10) |

FC13 (2010-15) |

FC14 (2015-20) |

FC15 (2020-26) |

|||||

|

Low-income States |

||||||||||

|

Bihar |

28,127 |

11.028 |

10.917 |

9.665 |

10.058 |

|||||

|

Uttar Pradesh |

39,371 |

19.264 |

19.677 |

17.959 |

17.939 |

|||||

|

Jharkhand |

51,365 |

3.361 |

2.802 |

3.139 |

3.307 |

|||||

|

Madhya Pradesh |

58,334 |

6.711 |

7.12 |

7.548 |

7.850 |

|||||

|

West Bengal |

72,202 |

7.057 |

7.264 |

7.324 |

7.523 |

|||||

|

Middle-income States |

||||||||||

|

Odisha |

71,622 |

5.161 |

4.779 |

4.642 |

4.528 |

|||||

|

Chhattisgarh |

72,236 |

2.654 |

2.470 |

3.080 |

3.407 |

|||||

|

Rajasthan |

74,009 |

5.609 |

5.853 |

5.495 |

6.026 |

|||||

|

Punjab |

1,12,119 |

1.299 |

1.389 |

1.577 |

1.807 |

|||||

|

Andhra Pradesh |

1,14,324 |

7.356 |

6.937 |

4.305 |

4.047 |

|||||

|

High-income States |

||||||||||

|

Maharashtra |

1,33,356 |

4.997 |

5.199 |

5.521 |

6.317 |

|||||

|

Kerala |

1,34,878 |

2.665 |

2.341 |

2.500 |

1.925 |

|||||

|

Tamil Nadu |

1,43,528 |

5.305 |

4.969 |

4.023 |

4.079 |

|||||

|

Karnataka |

1,54,123 |

4.459 |

4.328 |

4.713 |

3.647 |

|||||

|

Gujarat |

1,60,321 |

3.569 |

3.041 |

3.084 |

3.478 |

|||||

|

Haryana |

1,65,617 |

1.075 |

1.048 |

1.084 |

1.093 |

|||||

Note: Per capita income and share in net proceeds of FC14 and FC 15 are for bifurcated Andhra Pradesh

Source: FC Reports and National Statistical Office (NSO) data

A quick look at Table 2 shows that FC15 has been able to meet its mandate to some extent. Yet, assigning a big share to a developed state like Maharashtra is questionable.

Additional borrowing by states

Responding to the needs of state governments, whose resources had been seriously impacted by the pandemic, FC15 provided an additional borrowing limit of up to 2% of Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) in FY2020-21. Of the additional 2%, 0.5% was unconditional and the remaining 1.5% was conditional. According to the FC15 Report: “Out of the conditional component, 1 percent of the GSDP is to be given in 4 tranches of 0.25 percent, with each tranche linked to specified reform actions related to distribution of electricity, universalisation of the One Nation One Ration Card scheme, ease of doing business and revenues of urban local bodies. The remaining 0.50 per cent is permissible if milestones are achieved in at least three out of the four reform areas.”

This again imposes a larger burden on the states, who are already overburdened with their immediate fiscal needs. The base limit for net borrowings of state governments that had been fixed at 4% of GSDP in FY2021-22 (following the pandemic), was to fall to 3.5% in FY2022-23 and touch the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) target of 3% by 2025-26. Therefore, overall, there is no real relaxation for states that have greater requirement for borrowing as a result of increased social sector expenditure.

Grants to local governments

The conditions imposed on the release of grants to local bodies are alarming.3 FC 15 has recommended Rs. 2.4 lakh crore for rural local bodies, Rs. 1.2 lakh crore for urban local, and Rs. 70,051 crore for health grants through local government bodies, which adds up to a total of Rs. 4.36 lakh crore of grants to local bodies. The distribution of these grants is based on the criteria of population and area (weightage of 90 and 10%, respectively) and the rural-urban ratio is 65:35.

However, 60% of the grants have been made based on three entry conditionalities:

(i) setting up State FCs and executing their recommendations by March 2024

(ii) placing the audited accounts for the year before the previous year (t-2) and provisional accounts for the previous year (t-1) in the public domain

(iii) for urban local governments, notification of floor rates for property tax in FY2021-22, and after that annual increase matching the three-year average growth rate of GSDP.

Once these entry conditions are met further conditionalities are imposed for 60% of the grants, which are tied to water supply and sanitation. For urban local bodies, solid waste management is also included. This means only 40% of the grants can be spent according to local priorities. Thus, specific needs are ignored as the local bodies are compelled to meet the compliance of 60% to avail the rest of the grant.

How far are revenue deficit grants justifiable?

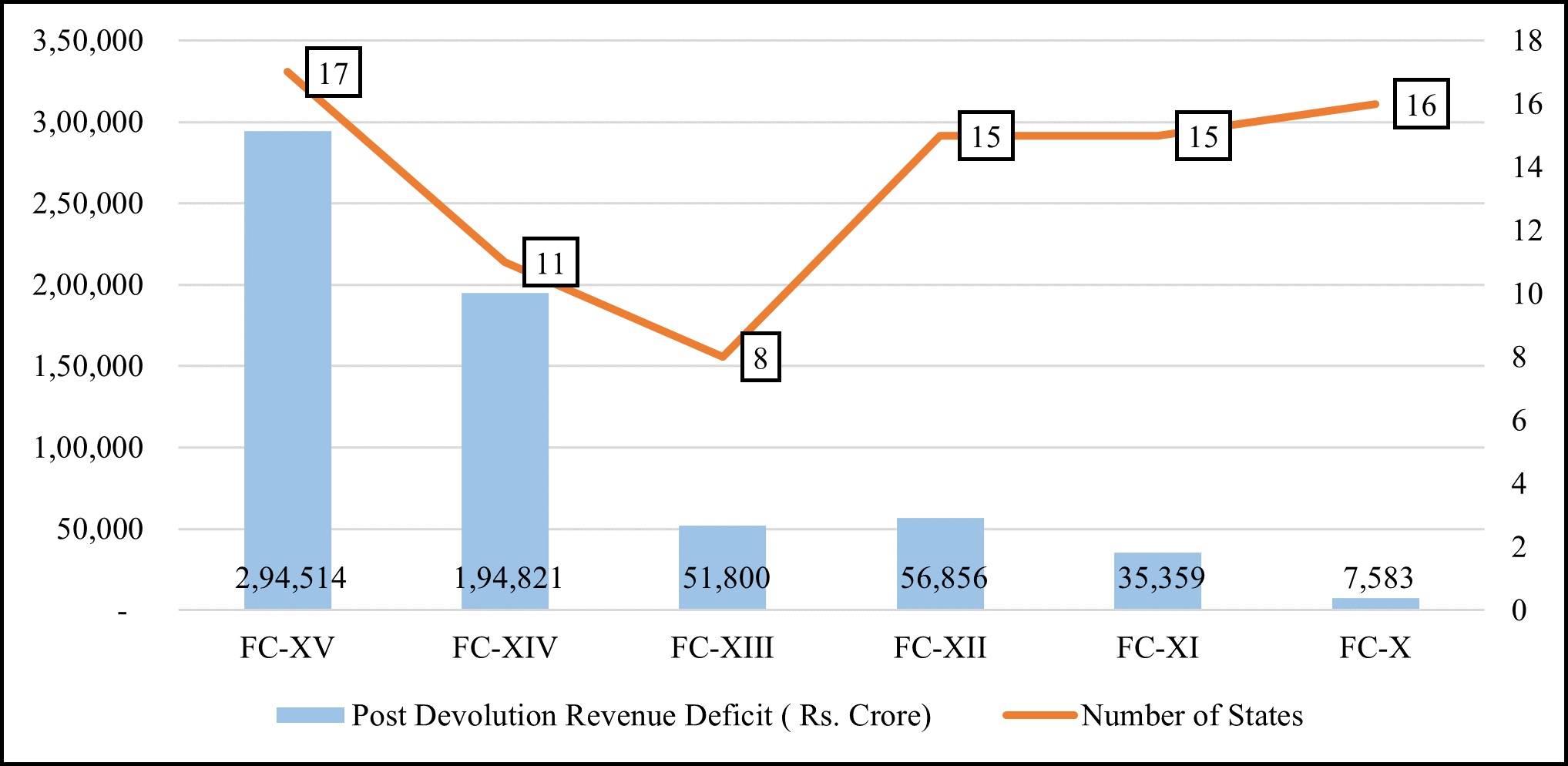

Under prudent financial management, revenue expenditure is not seen as growth inducing and should never exceed the revenue received. However, borrowing by states should be arrayed, especially for capital expenditure, which accelerates growth. Thus, states with revenue deficit should be supported with grants only when they ensure that all their borrowings are wholly channelled towards capital expenditure (Bhaskar 2018). Additionally, as per the FRBM Act, 2003, revenue deficit of all states should have been zero by FY2008-09 (Bhaskar 2018). By providing revenue deficit grant, FCs have been penalising the states who have strictly followed FRBM norms. Phasing out revenue deficit and promoting fiscal responsibility for both the Union and states was already suggested by FC9. However, in practice, the number of states getting revenue deficit grants have been gradually increasing (Figure 2). Thus, this kind of biased practice benefitting some states should be discontinued. Also, instead of promoting revenue deficit grant, the FC16 should give ‘development deficit grants’ to the states to help them from lagging behind. This type of grant will not only promote capital expenditure of states and but also lead to asset creation.

Figure 2. Distribution of revenue deficit grants

Conclusion

In fiscal federalism, the objective should not be only to raise ‘backward’ states to the average level or filling the revenue gap, but also to promote a continuous process whereby states at various levels of development keep progressing constantly, with the disparities among them gradually narrowing down. The aim of an emerging federation should be equalisation and motivation for higher tax effort and expenditure efficiency.

To have a judicious vertical and horizontal balance, the FC16 will have to consider the flaws in the transfers of the previous Commissions and design a formula that looks into the needs of the low-income states. Further, it will have to consider some recent political developments like the issue of freebies, old pension scheme, north-south federal fiscal debate etc., which will have an impact on the state exchequer. Instead of expanding the arbitrary and discretionary transfers under grants-in-aids (such as Revenue Deficit Grant), FC16 should focus on increasing the vertical share for more rational transfers under tax devolution.

The views expressed in this post are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the I4I Editorial Board.

Notes:

- Wicksellian Connection highlights a strong and logical connection between the two sides of the budget. The common links or connections between revenue and expenditure decisions and true demand functions lead to the efficient provision of public goods and services.

- A cess is meant for a specific purpose and provides necessary financial stimulus to a particular sector/area of the economy. The Centre acts as a custodian of funds collected under cess till these are appropriated for the mandated purpose. Similarly, surcharges are meant to be levied only for short periods.

- Grants to local governments, both rural and urban, are devolved as per the provisions under Article 280(3) (bb) and (c) of the Constitution.

Further Reading

- AP Kotha, V Agarwal, A Sengupta and RP Singh (2018), ‘Cesses and Surcharges: Report to the Fifteenth Finance Commission’, Report, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

- Bhaskar, V. (2018), “Challenges before the Fifteenth Finance Commission”, Economic and Political Weekly, 53(10): 39-46.

- Bird, RM and E Slack (2014), ‘Local Taxes and Local Expenditures in Developing Countries: Strengthening the Wicksellian Connection’, Rotman School of Management Working Paper No. 2423519.

- Das, K and AK Mishra (2008), ‘Horizontal Equity and the Thirteenth Finance Commission’, Working Paper No.185, Gujarat Institute of Development Research.

- Ganguli, Barna and Bakshi Amit Kumar Sinha (2020), “Progressiveness of Finance Commission: A Critical Review of Bihar”, Economic and Political Weekly, 55(43): 37-44.

- Mohan (2020), ‘Report of the 15th Finance Commission 2021-22 to 2025-26: What It Means for the States’, Commentary on India’s Economy and Society Series, No. 20.

- Sarma, JVM (1997), “Federal Fiscal Relations in India: Issue of Horizontal Transfers”, Economic and Political Weekly, 32(28): 1719–1723.

- Sharma, R, M Gupta and K James (2021), ‘Fiscal Federalism and Centrally Sponsored Schemes: Rethinking Article 282 of the Constitution’, Report, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

13 February, 2024

13 February, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.