In theory, debt waivers are expected to induce the optimal level of effort from the debtor for loan repayment. However, repeated waivers may distort household expectations about credit contract enforcements in the future. This column analyses the effect of Uttar Pradesh’s state-level debt waiver programme - announced right after India’s nationwide Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme – on consumption and investment behaviour of households.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the 2017 state elections in Uttar Pradesh (UP) with a thumping majority and once again the state government has a debt waiver package ready to be implemented. The BJP’s electoral manifesto had committed to write off loans of small and marginal farmers, which would approximately cost the government Rs. 0.37 trillion according to initial reports. This is not the first time governments have announced debt waiver policy in India: intervention in the credit market through household debt relief has been a fiscal policy adopted by many governments both at the central and state level since many years.

The support for debt waiver programmes comes from the theoretical argument underlying the Debt Lafer Curve (Sachs 1989), which shows that a very high level of outstanding debt reduces the incentive for the debtor to exert effort to repay. In such a situation a policy of debt forgiveness could induce the optimal level of effort from the debtor and maximise repayment (Krugman 1988). However, the static model overlooks the possibility that repeated debt waiver programmes might alter the expectations of debtors about enforcement of future credit contracts, which could adversely affect the level of effort. For instance, consider the case of debt waiver programmes in the context of agricultural credit markets wherein households obtain loans against collateral, land in most cases, which are freed once the loans are repaid. Households expect governments to intervene so that credit institutions do not seize their collateral in case of default. The expectation of low punishment is likely to affect household decisions regarding the utilisation of loans. Specifically, debt forgiveness is likely to disincentivise households to use loans for productive investments, which is required for repayment.

Past empirical research analysing the effectiveness of debt waiver programmes in India focusses on India´s largest debt waiver scheme, the nationwide Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS) . It has been found that ADWDRS1 has led to a delay in loan repayment, increase in defaults, and no significant productivity gains (Kanz 2012, De and Tantri 2014, Mishra 2017). In spite of the evidence against the effectiveness of the ADWDRS programme, many states continue to announce their own state-level debt waiver schemes. It is possible that state-level loan waiver schemes could address indebtedness problems that a generic national-level programme like ADWDRS is likely to miss.

Uttar Pradesh debt waiver scheme

In recent research, we evaluate the effectiveness of a state-level debt waiver programme, the UP Rin Maafi Yojana (UPRMY) announced in November 2011 (Chakraborty and Gupta 2017). Unlike the ADWDRS programme that was based on a land size cut-off for eligibility, a household qualifies under UPRMY based on the amount borrowed and repaid.

UP was the first state to announce its debt waiver programme, following ADWDRS. The timing makes it ideal to analyse how repeated generalised debt waiver programmes affect people’s consumption and investment decisions by changing their expectations about future waivers.

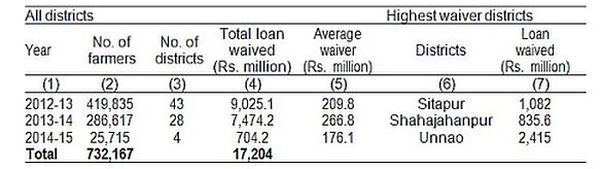

Table 1. Outline of Uttar Pradesh debt waiver scheme

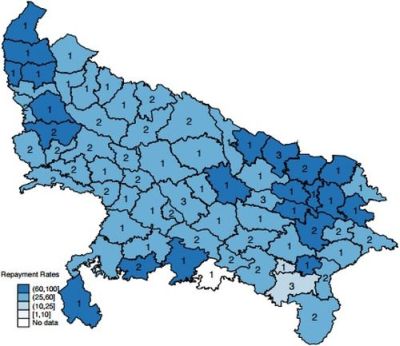

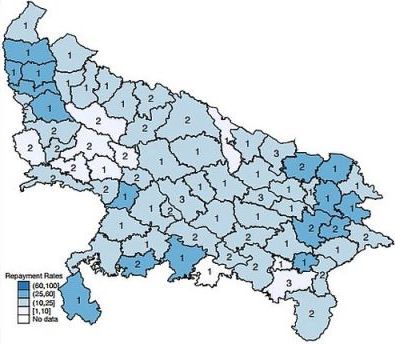

Under the UPRMY, a total amount of Rs. 17,204.2 million was disbursed as debt relief covering approximately 730,000 farmers from 74 districts over a period of three years from 2012-2015 (Table 1). Repayment rates changed dramatically after the announcement of the waiver programme across all districts of UP: the average rate fell from 25%-50% in 2010-11 (pre-announcement) to 10%-25% in 2011-12 (post-announcement) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Repayment rates of loans borrowed from UP Gramin Vikas Bank

Panel A: 2010-11 (Pre-announcement)

Panel A: 2010-11 (Pre-announcement)

Panel B: 2011-12 (Post-announcement)

Panel B: 2011-12 (Post-announcement) Note: Group 1 districts received the waiver in 2012-13; Group 2 in 2013-14; and Group 3 in 2014-15.

Consumption and investment behaviour of eligible vs. non-eligible households

We analyse the change in household behavior following the UPRMY using primary data collected in 2015 from 5,270 individuals in 770 households across six districts of UP. The districts were chosen to include regions from different phases of the programme roll-out. Auraiya and Kanpur Dehat received the waiver in 2012-13, And Agra and Firozabad in 2013-14. We also include Lakhimpur, the only district that did not receive the waiver at the time of data collection. Finally, we also chose Sitapur, which received the waiver and is right-adjacent to Lakhimpur. In each district a household qualifies for loan waiver if it had borrowed an agricultural loan of up to Rs. 50,000 from the UP Gramin Vikas Bank. Further, the household was required to have repaid at least 10% of the borrowed amount on or before the programme announcement date.

We compare the difference in the consumption and investment decisions of households potentially eligible for the loan waiver programme to otherwise similar households that are potentially not eligible. The analysis captures the differences between potentially eligible and not eligible households in districts that received the waiver vis-à-vis the differences between potentially eligible and not eligible households in districts that did not receive the waiver.

Since eligibility status is determined by loan size and percentage of prior repayment, we also explicitly control for these variables, in addition to household income, employment status, amount borrowed, interest rate on loan, religion, and sex of the household head.

Our findings suggest that eligible households in districts that received the waiver had higher consumption expenditure, approximately by Rs. 8,000 per year, as compared to non-eligible households. What is of greater concern is that eligible households also tend to spend significantly more on social events such as weddings, family occasions and so on.

In addition, we find that eligible households had no significant productivity difference compared to non-eligible households in districts that received the waiver. Given that the households in the same districts face similar agricultural shocks the insignificant productivity difference between eligible and not-eligible groups suggests a failure of the programme to achieve its desired goals. Eligibility of households for loan waiver frees them up from debts and builds expectations of future credit availability. Consequently, it reduces the incentives of households to allocate their budget towards more productive expenditures that would enable future debt repayment. We interpret these findings as indicators of moral hazard in the behavior of households when they receive waivers2 .

Implications for design of loan waiver programmes

Our research provides evidence that a blanket waiver scheme is detrimental for the development of credit markets. Repeated debt-waiver programmes distort household´s incentive structures, away from productive investments and towards unproductive consumption and willful defaults. These willful defaults, in turn, are likely to disrupt the functioning of the entire credit system by creating expectations amongst borrowers of weak enforcement of formal credit contracts. It is important to note, however, that our findings do not speak against loan waiver programmes altogether. Rather they warn against implementation of loan waiver programmes based on simplistic eligibility rules that do not account for the actual needs of the farmers and the agricultural shocks they have faced.

A well-designed loan waiver programme could enhance the overall well-being of the households by improving their productive investments, as opposed to distorting their loan utilisation and repayment patterns. One possibility is to formulate eligibility rules that depend on historical loan utilisation, investment, and repayment patterns. Another option is to explore alternate policy interventions like agricultural insurance. The desired intervention could then be the one, which nudges households into investing more now and increase long term productivity.

Notes:

- ADWDRS was a one-time settlement debt waiver scheme announced by the Government of India in 2008. It covered 43 million farmers and costed the government Rs. 716.8 billion.

- In this context, moral hazard refers to willful default on part of the borrowers. In other words, farmers borrow from banks for agricultural investment but do not undertake the investment. Instead they use up the loan for consumption. Consequently, they are unable to repay the loan in the future.

Further Reading

- Chakraborty, T and A Gupta (2017), ‘Efficacy of Loan Waiver Programs’, Working Paper.

- Chakraborty, T and A Gupta (2017), ‘Loan Repayment Behaviour of Farmers: Analysing Indian Households’, Working Paper.

- De, Sankar and PL Tantri (2014), ‘Borrowing culture and debt relief: Evidence from a policy experiment’, Asian Finance Association 2014 Conference Paper, 15 February 2014. Available here.

- Kanz, M (2012), ‘What does debt relief do for development? Evidence from India´s bailout program for highly-indebted rural households’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6258.

- Krugman, Paul (1988), “Financing vs. forgiving a debt overhang”, Journal of Development Economics, 29(3):253-268. Available here.

- Mishra, M (2017), ‘How agricultural debt waiver impacts beneficiary households’, Ideas for India, 2 February 2017.

- Raghuvanshi, U (2017), ‘Yogi Adityanath govt waives Rs 36,359-crore loan for UP farmers’, Hindustan Times, 11 April 2017.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D (1989), ‘The debt overhang of developing countries’, in G Calvo, R Findlay, P Kouri and J Braga de Macedo (eds.), Debt, Stabilisation, and Development: Essays in Memory of Carlos Díaz-Alejandro.

23 May, 2017

23 May, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.