Policymakers who aim only at lifting people out of poverty miss an essential fact: even as many people move out of poverty, many others fall back into it. This column argues that tackling poverty requires not only helping the existing poor, but also preventing the growth of future poverty

Heera Gujar was not born in poverty. Twenty-five years ago, Heera and his family were among the more prosperous households of his village. “We owned land,” he told me. “We also owned many cattle.” But things have since changed for the worse. Today his family are among the poorest people in the village, receiving community handouts on religious holidays.

Heera told me about the events that had led to this decline.“My father fell ill about 18 years ago. We must have spent close to 25,000 rupees on his treatment, but to no avail. When my father died, we performed the customary death feast, spending another 10,000 rupees. We sold our cattle and had to borrow money. We worked harder in order to repay these debts. Then, about ten years ago, my wife fell seriously ill, and she has still not recovered. We borrowed more money to pay for her medical treatments. More than 20,000 rupees were spent for this purpose. It became hard for us to keep up with our debts. Somehow we could make do for another two or three years. Then the rains failed for three years in a row, and that was the end of the road for us. We had to sell our land. Now, my sons and I work as casual labor, earning whatever we can from one day to the next.”

Twenty years ago, Heera and his family would not have been eligible for a “below-poverty-line” (BPL) card; today they are – and there are many others like them. Not only in Rajasthan, but across the country, thousands of people are becoming poor every day. Future poverty is being created even as some old poverty is reduced.

Together with colleagues, I have studied these trends in different states of India and other countries of the world. I met many people like Heera whose families were not poor 10 or 20 years ago, but who —because of identifiable and preventable events –have fallen into poverty with the passage of time. Unlike them, their children are being raised in poverty (see Krishna 2010).

Why is the widespread creation of poverty not being addressed with greater vigour? Why are policies and programmes focused single-mindedly on taking people out of poverty? Surely, planners cannot hold the belief that all poor people were born to this state?

Poverty creation and destruction

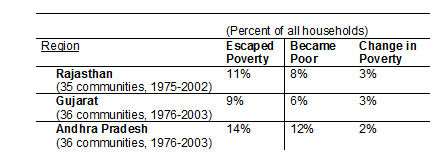

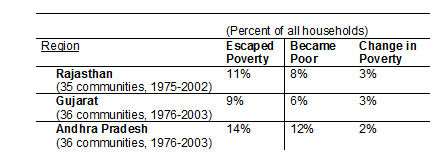

Our data and that of other investigators show clearly that poverty, like life, is simultaneously both created and destroyed. Large numbers of people are rising out of poverty – which is encouraging – but at the same time, many others are becoming chronically poor. Table 1 captures these findings for three parts of India.

Table 1. Escaping poverty and becoming poor

Similar trends are taking place elsewhere. The pool of poverty is, on the one hand, reduced as people move out, but on the other hand, this pool is refilled regularly, as people fall into poverty. In remote rural areas as well as throbbing metropolises, the number of those who have overcome poverty is close to the number of those who have become poor. Little wonder, then, that despite world-beating growth rates we are confronted with poverty rates that move at glacial pace.

Worse yet is the fact that those who fall into poverty find it exceedingly hard to move up and out. More than two-thirds of all people who fell into poverty 15 or more years ago were still poor at the time of our investigations.

This is a tragedy that could – and should –have been averted, and we are now trying to ameliorate this situation. By providing loans and grants and day-labouring opportunities, we try to make better the sorry situations that poor people face. But we are unable to prevent the problem arising in the first place: our policies deal with such tragedies only after they have arisen and become full-blown.

Prevention and opportunity

There are many opportunities to prevent the resurgence of poverty. As the example of Heera shows, people usually fall into poverty over a period of time, bit-by-bit and not all of a sudden. A chain of everyday events, rather than any single catastrophe, is most often implicated. Breaking this chain at one or more of the links will help slow the fall into poverty.

New policies are required for this purpose. Ramping up the rate of economic growth can help in many ways, but it will not reduce the frequency of poverty descents. In the US (whose per capita income at $48,000 is more than 30 times that of India), as many as 15%of the population live below the national poverty line – and this number, instead of falling, has grown of late. Even if by some miracle India were able to grow to US levels, it is not obvious that its poverty will go away.

Careful analyses of policy histories show that those countries – like Japan, South Korea, the Scandinavian countries, and some others – that have made the best progress against poverty in the 20th century have invariably adopted a two-track approach: active prevention accompanied by widespread opportunity.

The factors that drive people into poverty have to be identified. Preventive policies are best designed after knowing these facts. Simultaneously, a second set of policies must be in place, helping poor people rise as high as their capabilities and hard work individually permit.

Testing grandmother's tales

Like many other urban and middle-class Indians, I was raised to believe that people must be poor for some faults of their own. But these grandmothers’ tales disappeared like smoke when confronted with the reality that I experienced. Our team probed the factors associated with falling into poverty or remaining poor among a total of 35,000 households. Drunkenness, drug abuse, and laziness together accounted for no more than 3% of all instances (see Krishna 2010).

People are not poor because they wish to be poor or because of some character defect. Most have become poor due to influences beyond their personal control. These are the factors toward which preventive poverty policies must be geared. I will write of these factors in my next posting.

Meanwhile, let me introduce one other point. I met hundreds of talented and hardworking poorer people. Among the younger generations, especially, such instances are many. The problem is that within poorer communities of India talent is rarely able to connect with opportunity. Slum-born millionaires titillate in fiction because, like fairies and Superman, we do not have a chance to meet with them in real life.

And yet, it is not beyond comprehension that potential Ramanujams and Einsteins are being born within poorer households. Indeed, some of the young men and women whom I met –one of whom beat me handily at mental math games – while poor, have tremendous potential. The programmes we have to assist people like these do not, however, help connect such talents with wider opportunities.

Poverty of imagination

A poverty of imagination must be overcome that frames and informs social welfare policies. The problem of poverty creation does not appear on policymakers’ radar screens, because official statistics do not shed light upon the magnitude of this problem. Officials are concerned with reducing the stock of poverty, and that is all they measure: stocks – but not flows.

Measuring only stocks is hardly sufficient, however, for designing the policies that are required. Ascertaining the separate rates of escape and descent is indispensable because different types of policies are needed to address each of these trends.

Consider a hypothetical example in which the national stock of poverty, 32%in 2000, fell to 24%by 2010. How did this 8% reduction actually come about? Should we be gladdened or disheartened by this occurrence? The answer depends upon the underlying flows: Did (A) 8% of the population escape poverty, and no one fell into poverty (which is terrific); or (B) did 16%escape poverty, while 8% concurrently became poor; or (C) causing most despair, did 24% escape poverty and 16%fall into poverty.

Official data do not help distinguish between these (and innumerable other) possibilities, all of which can underlie the observed 8% net reduction. And so the problem remains.

Preventing poverty creation is both necessary and possible. Similarly, the paucity of opportunities available to poorer people has to be remedied. Helping more people rise above the poverty line is, no doubt, essential. But young people, like Chandru and Vasundhara and Bhoora, whom we will meet in a later posting, are capable of rising much further.

Further reading

- Attwood, DW (1979), “Why Some of the Poor Get Richer: Economic Change and Mobility in Rural West India”, Current Anthropology, 20(3):495-516.

- Bane, MJ and DT Ellwood (1986), “Slipping into and out of Poverty: The Dynamics of Spells”, Journal of Human Resources, 21(1):1-23.

- Baulch, B and JHoddinott (2000), “Economic Mobility and Poverty Dynamics in Developing Countries”, Journal of Development Studies, 36(6):1-24.

- Bigsten, A (2007), “Can China Learn from Sweden?”, World Economics, 8(2):1-24.

- Carter, MR and CB Barrett (2006), “The Economics of Poverty Traps and Persistent Poverty: An Asset-Based Approach”, Journal of Development Studies, 42(2):178-199.

- Jodha, NS (1988), “Poverty Debate in India: A Minority View”, Economic and Political Weekly, Bombay, November 1988, 2421-2428.

- Krishna, A (2010), One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How they Escape Poverty, Oxford University Press.

- Kwon, S (1998), “National Profile of Poverty”, in Combating Poverty: The Korean Experience, 29-60, United Nations Development Programme.

- Milly, DJ (1999), Poverty, Equality, and Growth: The Politics of Economic Need in Post war Japan, Harvard University Press.

- Ravallion, M (2001), “Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Looking Beyond Averages”, World Development, 29(1):1803-1815.

09 September, 2012

09 September, 2012

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.