The widespread disruption of economic activity caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has forced many to turn to MNREGA work in rural India. In this post, Aggarwal and Paikra show that current wages under the employment guarantee programme are even lower than the state minimum wage for agriculture in most major states. They present a brief history of how MNREGA wages are determined, and explain why these are so low.

Even though the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)1 entitles Suresh Ram and his family in Garhwa district in the state of Jharkhand, to 100 days of employment every year, he is forced to migrate to Andhra Pradesh to work as a manual labourer. For whatever little MNREGA work he could get in the past, he received payment with long delays. Further, the MNREGA wage rate (currently Rs. 194 per day in Jharkhand) is grossly inadequate to meet even basic needs. In Suresh’s opinion, it should be increased to Rs. 300.

MNREGA wages are lower than minimum wage for agriculture in many states

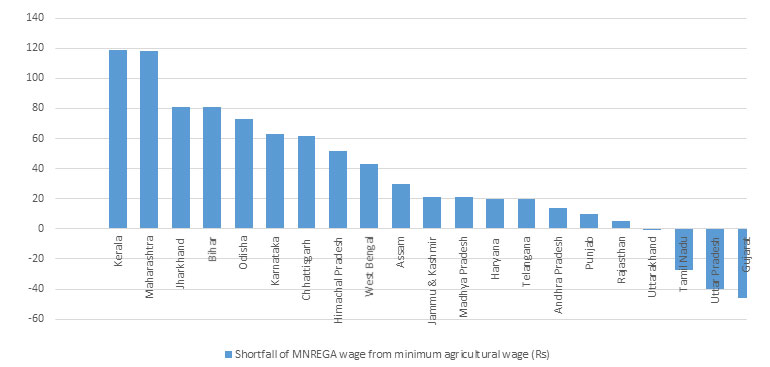

Jharkhand is not the only state where MNREGA wages are so unremunerative. Daily MNREGA wage rates in Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Himachal Pradesh are also below Rs. 200. Currently, the MNREGA wage rates of at least 17 of the 21 major states are even lower than the state minimum wage for agriculture. The shortfall is in the range of 2-33% of the minimum wage (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1. Minimum agricultural wages vs. MNREGA wages (major states)

|

|

Latest available minimum agricultural wage |

MNREGA wage rate, 2020-21 (Rs. /day)* |

Shortfall of MNREGA wage from minimum agricultural wage (Rs.) |

|

|

Amount (Rs. /day) (source in hyperlink) |

Effective from |

|||

|

May-17 |

291 |

|||

|

356 a |

Jul-19 |

238 |

118 |

|

|

Oct-19 |

194 |

81 |

||

|

Apr-20 |

194 |

81 |

||

|

Oct-18 |

207 |

73 |

||

|

Apr-19 |

275 |

63 |

||

|

Apr-20 |

190 |

62 |

||

|

Apr-19 |

198b |

52 |

||

|

Jan-20 |

204 |

43 |

||

|

Nov-16 |

213 |

30 |

||

|

Oct-17 |

204 |

21 |

||

|

Oct-19 |

190 |

21 |

||

|

Jul-18 |

309 |

20 |

||

|

257 a |

Apr-19 |

237 |

20 |

|

|

Oct-18 |

237 |

14 |

||

|

Mar-17 |

263 |

10 |

||

|

May-19 |

220 |

5 |

||

|

Jun-15 |

201 |

-1 |

||

|

229 c |

Sep-19 |

256 |

-27 |

|

|

Oct-16 |

201 |

-40 |

||

|

Sep-16 |

224 |

-46 |

||

Source: MNREGA wage rates data are from here. These are prescribed wage rates – actual wages are sometimes lower due to shortfall from productivity norms under the piece-rate system.

Notes:

- a Lowest among zone-specific minimum wages.

- b Rs. 248 in ‘scheduled tribe areas’.

- c For six hours of work per day.

- 'Unskilled' wages (non-agriculture) are higher (in some cases much higher) in some states.

- States are ranked in descending order of shortfall (last column).

- In cases where minimum wages are monthly wages, these were divided by 26 to estimate daily wages.

Figure 1. Shortfall of MNREGA wage from minimum agricultural wage (Rs.)

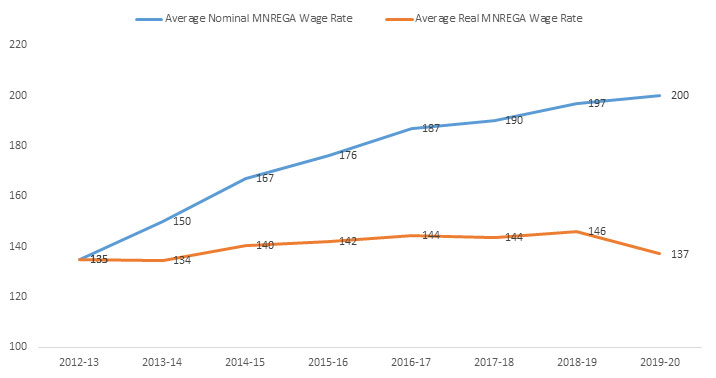

Figure 2. Comparison of average MNREGA nominal wage and real wage

Source: Official MNREGA website and RBI data.

Note: The average nominal MNREGA wage rate is calculated as a weighted average of state-specific MNREGA wage rates, using person-days of MNREGA employment as weights. The average real MNREGA wage rate is calculated by deflating the average nominal MNREGA wage rate using Consumer Price Index of Agricultural Labour (CPIAL).

Brief history of how MNREGA wages are determined

So why are MNREGA wages so low? A brief review of the history of how they are determined is instructive to understand the reasons. The employment guarantee act gives the central government two options for determining the MNREGA wage rate. The first is that MNREGA workers are paid the state minimum wage for agricultural labourers. The second is that the central government notifies separate wage rates for MNREGA. Till 2008, MNREGA wages were fixed as per the first option. From 1 January 2009, the central government switched to the second option and effectively capped the MNREGA wage rate at Rs. 100. It argued that since the entire wage burden of the Act is borne by the Centre, state governments have an incentive to inflate minimum wages. Consequently, over time, the MNREGA wage rate for many states has become lower than their minimum wage for agriculture.

As per the Supreme Court ruling in Sanjit Roy vs. State of Rajasthan (1983), payment of less than the minimum wage amounts to “forced labour”, punishable under Article 23 of the Indian Constitution. In 2010, the Central Employment Guarantee Council’s (CEGC) Working Group on Wages also deemed the delinking of MNREGA from minimum wages as illegal. The group made an ‘emergency recommendation’ of unfreezing MNREGA wages and indexing them on the price level. To ensure a sustained reconciliation of the MNREGA wage policy with the Minimum Wages Act, it proposed three options: (1) payment of minimum wages for agricultural labourers to MNREGA workers; (2) central government to fix price-indexed MNREGA wage rates that are determined in consultation with representatives of state governments and workers’ organisations; and (3) amending MNREGA in a manner that the central government pays up to a price-indexed national level, and state governments pay the difference between their minimum wage and the national level.

The central government implemented the emergency recommendation, but made no attempt to reconcile MNREGA with the Minimum Wages Act. This led to the stagnation of MNREGA wages in real terms, from then onwards. Over the past eight years, the nominal MNREGA wage at the national level2 has increased from Rs. 135 in 2012-13 to Rs. 200 in 2019-20. Meanwhile, the corresponding real MNREGA wage has remained more or less the same. Market wages, on the other hand, have been slowly rising in real terms during this period.

In 2015, the Mahendra Dev Committee constituted to advise on the matter of MNREGA wage revision, recommended that the baseline for MNREGA wage indexation should be the current minimum wage rate for agricultural labourers, or the current MNREGA wage rate, whichever is higher. The central government ignored this recommendation and instead constituted yet another committee to look into the matter of fixing MNREGA wage rates. Unlike the CEGC’s Working Group on Wages and the Mahendra Dev Committee, this committee (headed by the Additional Secretary of the Ministry of Rural Development, Nagesh Singh) did not include any independent expert or representative of workers. The Nagesh Singh Committee made a modest recommendation of changing the index for revising MNREGA wages as per the price level, from the CPIAL to the Consumer Price Index for Rural Labourers, which is considered more representative of the rural consumption basket. A 2018 Right to Information query to learn about government action on this recommendation and the basis for calculation of MNREGA wage rates was turned down by the Ministry.

Need to expand MNREGA in Covid times

The unremunerative levels of MNREGA wages, together with the chronic shortage of work and delays in payments, have discouraged many like Suresh Ram from taking up MNREGA work. But the widespread disruption of economic activity caused due to the Covid-19 pandemic has forced several people to turn to MNREGA in rural India. Anticipating a surge in demand for MNREGA work this year, the central government allocated an additional Rs. 400 billion for the programme in May. But since the lockdown began, it has neither increased the MNREGA wage rate nor enhanced the guarantee of work. These measures would be amongst the most effective to provide some relief in the ongoing economic crisis.

Notes:

- MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work.

- Nominal MNREGA wage at the national level is calculated as a weighted average of state-specific MNREGA wage rates, using person-days of MNREGA employment as weights.

05 October, 2020

05 October, 2020

By: ajay 05 October, 2020

the rates should be compared to market rates. when legal minimum wages are more than market rates, it leads to corruption. workers get market rate wages. the extra is pocketed by corrupt powerful people.