Asset declarations, requiring politicians to disclose their financial information, are becoming increasingly common across the world. In India, financial declarations are part of public affidavits filed as a prerequisite for candidacy for political office. Using data from Indian affidavits, along with original experimental and survey data, this article examines how information on politicians' wealth accumulation may impact citizens’ evaluations of politicians and their voting behaviour.

Asset declarations – requiring politicians to disclose their financial information, such as income, property, and debts – are becoming increasingly common across the world. The number has increased from just 22 countries in 1980 to over 160 countries in 2015. At present, more than 80 countries, including India, make these disclosures public to some extent (Rossi et al. 2017). As a result, financial disclosures have become the focus of increasing public interest in India and abroad.

In India, financial declarations are part of public affidavits filed as a prerequisite for candidacy for political office. The disclosures contain a snapshot of candidates' household-level income (from tax returns), property, and debts1. The affidavits therefore provide citizens with a window into their representatives’ wealth.

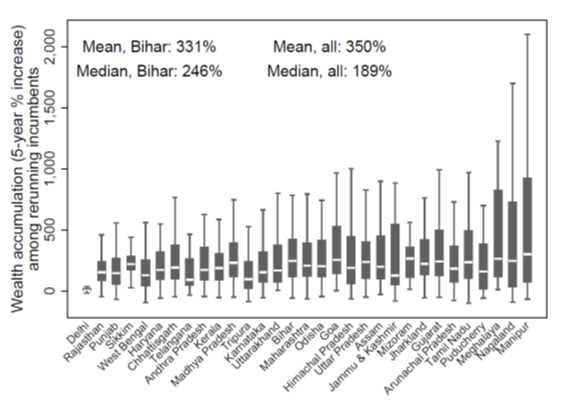

For candidates who run in consecutive elections, the disclosures also allow for the calculation of changes in wealth, by comparing the information from successive disclosures. Such calculations, done routinely by the press and civil society organisations, point to very large increases in wealth among candidates for political office – particularly among office-holders (Fisman et al. 2014). For example, the average nominal wealth increase among Indian state legislators during a five-year legislative term is around 350% (see Figure 1 for state-by-state data). By comparison, over the same time span, Indian households have seen an average increase in wealth of mere 17%.2

Figure 1. Wealth accumulation rates among state legislators in Indian states

India is not unique in this regard. The data from financial disclosures in several other countries similarly reveal that political elites enjoy substantial wealth accumulation while in office, usually higher than among similar individuals not in office (Klašnja 2015, Querubin and Snyder 2013). Such evidence may – or even should – raise suspicions among citizens. However, currently, we know little about how information on politicians' wealth accumulation may impact citizens’ evaluations of such politicians.

In recent research (Chauchard et al., forthcoming), we address this gap in knowledge. Relying on data from Indian affidavits, and using original experimental and survey data, we explore three interrelated questions: How do citizens react to information about wealth and wealth accumulation of politicians in office? To what extent do they associate large wealth accumulation with corruption and other bad outcomes? How may these evaluations impact citizens’ electoral behaviour, and in turn, potentially the election of wealth-accumulating politicians?

What citizens think of wealth accumulation by politicians

To answer these questions, we fielded two surveys to socially diverse samples of citizens across Madhepura district, in the northern Indian state of Bihar3. In Bihar, the rate of state legislators’ wealth accumulation is similar to the national average (see Figure 1). The key part of our first survey is a lab-in-the-field experiment, in which our respondents evaluated several fictional but realistic politician profiles. We randomly varied a number of politician characteristics, both those commonly discussed and examined in Indian politics (Chandra 2004, Chauchard 2016, Vaishnav 2017), such as party affiliation, ethnicity, and criminality, and for the first time, the information about politicians' wealth and wealth increase. This experiment serves our research questions well, by allowing us to causally identify and compare the weight that respondents place on politicians’ wealth accumulation relative to other politician characteristics, and explore potential interactions between wealth accumulation and other politician and respondent characteristics likely playing a role in citizens’ electoral evaluations.

We complement our experimental survey with a second survey, the goal of which was to evaluate citizens' awareness of asset disclosures, recollection of the information contained in them, and the precision of respondents' guesses about actual representatives' wealth accumulation.

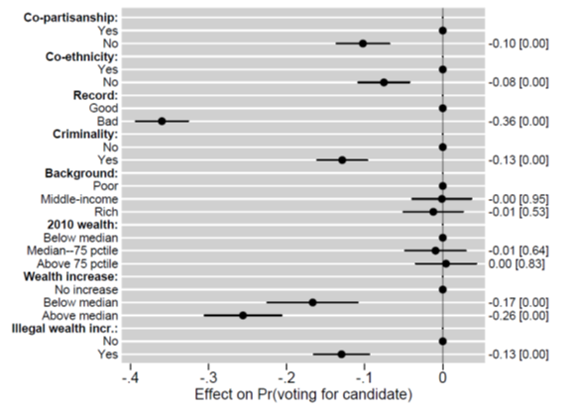

Results from the experiment indicate that our respondents strongly disapprove of wealth accumulation in office. As Figure 2 shows, plotting the effect of each politician characteristic shown in the experiment, citizens are, on average, less likely to cast a hypothetical vote for politician profiles with greater wealth increase. For example, citizens who saw a politician profile with above-median increase in wealth were, on average, 35 percentage points less likely to cast a hypothetical vote than for an identical politician with no wealth increase. Respondents also view greater ‘wealth accumulators’ as more corrupt, and more prone to violence, an important problem in Bihari and Indian politics (Vaishnav 2017).

What is more, except for the effect of a politician’s record in office – their track record (or lack thereof) in serving the constituency – wealth accumulation had the most pronounced effect on citizens’ evaluations of politicians, even larger than the effect of a politician’s caste (measured by whether the politician was a co-ethnic of the respondent or not), or party (measured by whether the politician belonged to the respondent’s preferred party or not). In contrast to the effect of wealth accumulation, we find no evidence that a politician’s wealth mattered: when holding politician’s wealth accumulation constant, citizens evaluated rich and poor politicians very similarly4.

Figure 2. The effect of wealth accumulation and other politician characteristics on citizens’ hypothetical vote choice

Why wealth-accumulating politicians are re-elected

Our respondents’ strong negative reactions to wealth accumulation seem at odds with the fact that many Indian politicians who rapidly accumulate wealth during their tenure manage to win re-election5. While the election and re-election of wealth accumulators may in part owe to dynamics we cannot explore in our research – for example, wealth-accumulating politicians' usefulness to parties due to their campaign-financing prowess – we utilise our data to explore several possible mechanisms by which citizen behaviour may contribute to the prevalence of large wealth accumulation among politicians in office. Relying on the data from our second survey, we first find that the majority of our respondents are unaware of the disclosures and their contents, and lack a precise sense of the size of their actual representatives' wealth increase. This suggests that the disconnect between the high re-election rates of wealth accumulators in the real world and the strong disapproval of wealth accumulation in our experiment may derive from citizens’ lack of familiarity with the disclosures – despite their public availability.

Citizens’ low awareness, however, may not be the only reason for this disconnect. Returning to our experiment, we explore the extent to which the broader structure of citizens’ preferences may prevent negative reactions to information about politicians' wealth accumulation from potentially having a larger impact in actual elections. While our respondents' disapproval of large wealth increases by incumbents is overall robust, two results are worthy of note. First, as can be seen in Figure 2, respondents weighed information about a politician's record in office noticeably more heavily than information about wealth accumulation. This was the case even when we explicitly presented in the experiment that wealth accumulation was deemed to be suspicious. Therefore, reactions to information about wealth accumulation, however negative they might be, may not be strong enough to prevail over reactions to politicians' other characteristics or to performance on other dimensions.

Second, we find that members of the largest caste in Bihar (Yadavs) tolerate large wealth increases by politicians from the party most closely associated with representing Yadavs – the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) party. While we remain careful about this finding in light of sample size limitations, this pattern broadly suggests that citizens may be heterogeneous in their response to information about wealth accumulation, with some subgroups being relatively tolerant of wealth accumulation in office, especially among politicians from their preferred party or own caste group6.

Policy implications

These findings suggest that the potential benefits of increased transparency may be limited by the implementation of the policy, the demographics of the populace, and other contextual factors. Our results show that voters are largely unfamiliar with the content of the disclosures. Coupled with our finding that citizens strongly disapprove of large wealth accumulation, the optimistic takeaway is that better efforts to publicise the information from the disclosures may strengthen electoral accountability mechanisms. However, in order for information to reach its full potential and have a real impact at the polls, voters need to not only be aware but also understand the information. High illiteracy rates and low citizen engagement in Indian political and civic life are probably important challenges in this regard.

Our other results potentially further temper the optimism that financial disclosures may help voters in constraining their representatives’ wealth accumulation. Even when citizens are informed about the disclosures, politician integrity needs to feature prominently in their voting decisions. This too can be challenging if voters are forced to prioritise demanding basic public services that would otherwise be lacking – as evidenced by the strong emphasis our respondents placed on the hypothetical politicians’ record in office. Since institutions, groups, and organisations disseminating information from financial disclosures often have little control over these contextual factors, our findings suggest that such information dissemination initiatives are not a panacea to larger problems of the Indian political system.

Notes

- In addition to financial information, the affidavits contain contact and basic family information, candidate's age, profession, education, criminal record, and party affiliation.

- The estimate for Indian state legislators is based on data from the Association for Democratic Reforms; for Indian households, the source is the India Human Development Survey.

- The studies took place in April-June 2015. In the lab-based survey, 1,020 people were surveyed. For the field survey, the sample size was 323.

- The same goes for politician’s family background: our respondents judged politicians coming from rich families very similarly to rags-to-riches politicians or the ones with a middle-class background.

- Incumbents with greater wealth accumulation have higher re-election rates than incumbents with lower wealth increase in office.

- That said, in the overall sample, we do not find evidence that respondents, on average, formed biased evaluations of wealth accumulation – wealth accumulators from the same caste or the most preferred party were judged no differently than those from other castes or less preferred parties.

Further Reading

- Chandra, K (2004), Why Ethnic Parties Succeed: Patronage and Ethnic Head Counts in India, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Chauchard, Simon, Marko Klasnja and SP Harish, “Getting Rich Too Fast? Voters’ Reactions to Politicians’ Wealth Accumulation in India”, Journal of Politics, Forthcoming.

- Chauchard, Simon (2016), “Unpacking Ethnic Preferences: micro-level Evidence From India”, Comparative Political Studies.

- Rossi, IM, L Pop and T Berger (2017), ‘Getting the Full Picture on Public Officials: A How-to Guide for Effective Financial Disclosure’, The World Bank, Washington DC.

- Fisman, Raymond, Florian Schulz and Vikrant Vig (2014), “Private Returns to Public Office”, Journal of Political Economy, 122(4): 806-862.

- Fisman, R (2018), ‘Sunlight as disinfectant : Disclosure requirements and corruption in India’, Ideas for India, 22 June 2018.

- Klašnja, Marko (2015), “Corruption and the Incumbency Disadvantage: Theory and Evidence”, Journal of Politics, 77(4): 928-942.

- Querubin, Pablo and James M Jr. Snyder (2013), “The Control of Politicians in Normal Times and Times of Crisis: Wealth Accumulation by U.S. Congressmen, 1850-1880”, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 8: 409-450.

- Vaishnav, M (2017), When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics, Yale University Press, New Haven.

10 August, 2018

10 August, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.