Despite close geographical proximity of India and Pakistan and implementation of SAFTA almost a decade ago, trade potential between the two countries remains largely unexploited. This column analyses trends in Indo-Pak trade in agriculture, which constitutes 43.6% of total Indo-Pak trade, and highlights opportunities for expanding trade in this sector.

Despite the advantage of close geographical proximity, India and Pakistan did not trade much until the late 1990s. Bilateral trade started expanding in the 21st century, and picked up momentum after the SAFTA (South Asian Free Trade Area) agreement, which came into effect in 2006. In this column, we focus on the potential of expanding agricultural trade, which constitutes 43.6% of the total trade between the countries. (Chand and Saxena 2014).

Trends in Indo-Pak agricultural trade

The SAFTA effect

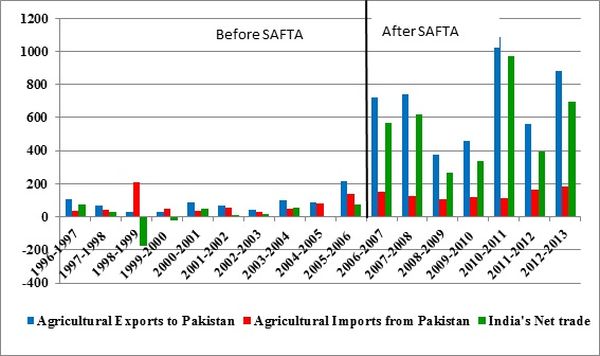

The SAFTA effect on India-Pakistan trade is much sharper for agricultural trade as compared to overall trade between the two countries. Agricultural trade trends between the two countries reveal a clear but one-time increase in 2006-07, the year in which the SAFTA agreement was implemented. After 2006-07, India’s agricultural exports to Pakistan remained higher than Pakistan’s agricultural exports to India in all years but with a lot of variation over the years (Figure 1); Pakistan’s agricultural exports, although small, did not fluctuate as much.

Figure 1. India’s agricultural trade with Pakistan (US$million)

Source: EXIM Databank, Government of India

Source: EXIM Databank, Government of India

What is traded and why?

The composition of India’s agricultural exports to Pakistan has undergone significant change over time and has become more diversified. During the late 1990s, sugar and confectionery accounted for more than half of the total agricultural exports from India, and close to one-fifth of exports consisted of coffee, tea, mate (a beverage) and spices. Thus, these two groups accounted for almost 80% of India’s agricultural exports to Pakistan (Chand and Saxena 2014). Cotton emerged as a significant item of export from India to Pakistan since 2003-04.

Pakistan’s agricultural exports to India were dominated by a few commodities. In the late 1990s, sugar and confectionery accounted for 69% of Pakistan’s agricultural exports to India1. The share of sugar dropped to 14.6% in the mid-2000s and almost dried up after that, with Pakistan becoming a large net importer of sugar. Edible fruits and nuts (mainly dates) emerged as the largest item in Pakistan’s agricultural exports to India (48.4% of total). The second most important item in recent years has been cotton fabric and textiles, with a 30% share in total agricultural exports from Pakistan to India.

The trade pattern of the past 15 years indicates that Indo-Pak agricultural trade can be classified into three categories: (a) trade for domestic stabilisation, (b) trade, of more or less permanent nature, based on comparative advantage, and (c) trade in specialised products, which are generally not produced in Pakistan. India’s major exports to Pakistan, like sugar, onion and even cotton, are meant largely for augmenting Pakistan’s domestic supply due to production shocks. Due to close geographical proximity, India has also imported items such as onions from Pakistan to stabilise domestic supply. Such trade is not based on strong comparative advantage but on climatic factors causing production fluctuations in the destination country.

Studies show that there is considerable delay in arranging import on both sides to address domestic shortages (Chand 2012). Suitable mechanisms need to be developed for liberalised trade in such commodities to address price shocks that hurt consumers and also adversely affect the economy. Bilateral trade is a cost effective and efficient instrument to address price and market volatility in the two countries.

Comparative advantages

Both countries have comparative advantage in the export of some commodities to the other. For India, these include tomato, cane sugar, onion, fresh vegetables, cotton (carded and combed), groundnuts, coarse cereals (as feed) and dairy products. While tea is a traditional Indian export, the comparative advantage has been declining over time. In the case of raw cotton, India’s comparative advantage has increased after the adoption of Bt cotton technology. Due to climatic factors, Pakistan has an inherent and sustained comparative advantage in dates. Moreover, Pakistan enjoys a comparative advantage in leather, hides, skins and woven fabrics.

The greatest trade advantage lies in cotton textiles and woven fabrics - both countries have integrated themselves in a value chain wherein India exports raw staple cotton to Pakistan, and imports value-added textiles and fabrics from Pakistan. Similar customer taste and preferences for fabrics/ textiles and designs in the neighbouring states of Punjab (in Pakistan) and Kashmir have further enhanced cotton trade between the two countries. There is considerable scope for promoting exports of specialised items by India whose trade is stable and growing, to give a further boost to overall agricultural trade between the two countries. These include products with unique attributes like herbs, medicinal and aromatic plants, and some cereals such as buckwheat (kuttu) and psyllium (isabgol).

What restricts trade across the Indo-Pak border?

Despite implementation of SAFTA, some strong tariff and non-tariff barriers continue to restrict agricultural trade between the two countries. This requires action in the following areas: (i) trade facilitation, (ii) further lowering of tariffs, (iii) pruning the negative list2, and (iv) removal of non-tariff trade barriers3.

Of these, trade facilitation is most important for increasing bilateral trade. It involves simplification of custom and other border formalities, transport linkages, transparency in regulatory provisions, improved logistics for rail, road, air and maritime transport, better information network etc. Improved trade facilitation and logistics will reduce the transaction cost of trade, which is more significant than tariff. India and Pakistan must promptly take measures, individually and together, to achieve higher trade facilitation. Pakistan should also consider giving ‘Most Favoured Nation’4 status to India.

Differences in the level of agricultural subsidies between India and Pakistan are cited as an important reason for not liberalising Pakistan’s agricultural import from India. As there is a huge difference in the size of the agricultural sector in the two countries, comparisons of subsidies make better sense in terms of ratio or share. In 2010-11, the level of input subsidies5 per hectare of net cropped area was US$225.6 in India and US$168.1 in Pakistan. India subsidised its agriculture to the tune of 8.8% of the value of agriculture production as compared to 4.9% in Pakistan (National Accounts Statistics 2012, Pasha and Pasha). These comparisons show that Indian farmers have a benefit of almost 4% over Pakistani farmers in terms of subsidies and this can be factored into trade policy through measures like countervailing duty6. Therefore, higher levels of subsidy in Indian agriculture compared to Pakistan should not be a major issue in promoting trade between the two countries.

Expanding trading opportunities

There are two types of opportunities to expand agricultural trade between the two countries – one, by replacing a third country’s trade and second, through creation of new trade. Geographical proximity favours both these situations in the case of India and Pakistan. There is little scope for expanding exports of a few items such as meat products, from India to Pakistan, although these form a large share of India’s exports to the world. This is because Pakistan’s entire import demand s already being met by India, implying no scope for expanding meat exports to Pakistan by substituting third country export. In contrast, there is scope for expanding export of dairy products and eggs to Pakistan. Pakistan’s import demand for dairy products and eggs is US$114 million and less than one-tenth of it comes from India, despite the fact that India’s total export volume for these products is 2.5 times the import demand in Pakistan.

There is vast scope for India to promote agricultural exports to Pakistan by taking advantage of the geographical proximity, which gives it an edge over the rest of the world. Unlike India, Pakistan has limited opportunities to promote agricultural exports to India because Pakistan’s exports match India’s import needs for only a few commodities. Pakistan’s major agricultural export is cereals and India is itself a large exporter of cereals. Where India is deficit, Pakistan is not surplus. Therefore, the scope for Pakistan to replace third country export to India is limited. However, Pakistan can take advantage of the rapid diversification of demand for several products in India like a variety of fruits and vegetables. This will require addressing supply-side factors in Pakistan and enhancing their domestic production.

Another neglected area so far, related to agricultural trade, is the trade in technology. Agriculture in both countries faces some serious challenges, and there are tremendous opportunities for science-led agricultural growth. The scope to take advantage of breakthroughs in modern science and their applications in agriculture, using spillovers from developed countries, is shrinking. Modern research also requires large amounts of capital and a high level of skill and knowledge. India and Pakistan can benefit immensely through trade in technology in the agricultural sector.

Notes:

- There were different items under ‘sugar and confectionary’ being exported by India and imported into India in the late 1990s.

- Negative list refers to a list of items that cannot be imported by Pakistan from India.

- Non-tariff barriers include quotas, levies, embargoes, sanctions, and other restrictions.

- ‘Most Favoured Nation’ (MFN) is a clause that a country grants to another to give them specific trade advantages such as reduced tariff and non-discriminatory market access. India granted Pakistan MFN status in 1996, however, Pakistan is yet to give MFN status to India.

- An input subsidy reduces the price that a farmer pays for an agricultural input. The difference between the market price of the agricultural input and the price paid by the farmer is the amount of the subsidy.

- Countervailing duties are meant to level the playing field between domestic producers of a product and foreign producers of the same product, because the domestic producers can afford to sell it at a lower price due to subsidy from their government.

Further Reading

- Chand, R and R Saxena (2014), ‘Bilateral India-Pakistan Agricultural Trade:Trends, Composition and Opportunities’, ICRIER Working Paper 287.

- Chand, Ramesh (2012), ‘International trade, regional Integration and food security in south Asia with special focus on LDCS’, UNCTAD and Common Wealth Secretariat.

- National Accounts Statistics (2012), Central Statistics Office, Government of India.

- Pasha Hafiz Ahmed and Pasha Aisha Ghaus (Undated), ‘Non-Tariff Barriers of India and Pakistan and their Impact’, Institute of Public Policy Beaconhouse, National University Pakistan, USAID.

02 April, 2015

02 April, 2015

By: Miruthula 11 October, 2018

The agriculture industry and farmers due to 5% GST rates on agricultural products. After the introduction of GST influencing the common people living in all section of the society. Agriculture Ministry discussed issue of deep irrigation machine prices with the finance ministry in the recent 25th GST council meeting. The GST council has now reduced GST rate on Sprinkles and Nozzles which was earlier attracting 18% now applicable 12% GST. As the government want to focus on deep irrigation techniques to support agriculture practices in India.