India’s ‘Look East’ policy picked up steam with the conceptualisation of the Indian-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement in 2003. This column analyses the broad trends in India-ASEAN trade over the past

East and Southeast Asia are important economic blocks in the world trade architecture today and together command more than a third of world trade. Since the beginning of its liberalisation process, India has adopted a ‘Look East’ policy1 which picked up steam with the conceptualisation of the India-ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 20032. The agreement for goods was signed in 2009 and implemented in 2010. The agreement for services and investment was signed in 2014 and news reports indicate it was due to be implemented from July 2015.

Several studies have assessed the possible impact of the India-ASEAN FTA and have reached different conclusions. Pal and Dasgupta (2008) inferred that short-term benefits would accrue mostly to ASEAN countries. Veeramani and Gordhan (2011) concluded that Indian imports of plantation crops like tea, coffee and pepper would increase through channels of trade creation. Sikdar and Nag (2011) concluded that Indian exports and imports would both increase from the bigger trade partners in ASEAN, which are Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam. However, allocative inefficiency might lead to welfare loss in India3. Bhattacharya and Mandal (2014) have found negligible tariff elasticity of trade for most products, that is, tariff changes may lead to only less than proportionate changes in trade for most products.

In this column, I analyse the broad trends in India-ASEAN trade, delve into the challenges involved in the economic relationship, and explores possible options for the way forward.

India-ASEAN trade trends

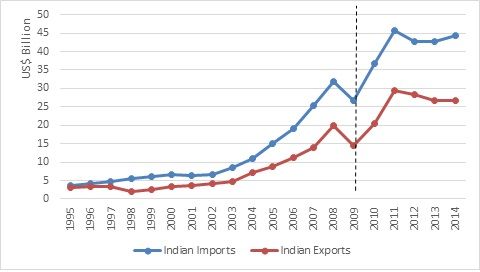

India-ASEAN trade has grown at an average annual rate of 19% during 2004-2014 with a fall in 2009 due to the global financial

Figure 1.India-ASEAN merchandise trade

Source: Constructed by the author using data from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank.

Source: Constructed by the author using data from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank. Note: The dotted line for year 2009 implies the signing of India-ASEAN FTA.

Trade architecture in ASEAN: India’s challenges and way forward

Trade in ASEAN countries has been redefined in terms of trade in value added through global value chains (GVCs) (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), 2011). Developing countries like India, which need to kick-start their manufacturing sector, have an opportunity to integrate into the value chain by participating in one particular segment of the value chain of a given industry (Kowalski et al. 2015). In order to strengthen trade and investment relations with ASEAN, India would need to be competitive and participate in the value chain of particular industries.

Table 1.

|

Industry |

ASEAN |

India |

|

Total |

54.4 |

42.3 |

|

Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing |

2.8 |

1.4 |

|

Mining and quarrying |

8.6 |

2.1 |

|

Food products, beverages and tobacco |

2.0 |

0.4 |

|

Textiles, textile products and footwear |

4.5 |

1.9 |

|

Wood, paper, paper products, printing and publishing |

0.9 |

0.3 |

|

Chemicals and non-metallic mineral Products |

5.7 |

4.5 |

|

Basic metals and fabricated metal products |

1.3 |

2.1 |

|

Machinery and equipment, not elsewhere classified( |

1.8 |

0.9 |

|

Electrical and optical equipment |

14.3 |

3.0 |

|

Transport equipment |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Manufacturing |

0.6 |

8.4 |

|

Electricity, gas and water supply |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Construction |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Wholesale and retail trade; hotels and restaurants |

4.3 |

3.2 |

|

Transport and storage, post and telecommunication |

3.4 |

2.7 |

|

Financial intermediation |

1.0 |

1.3 |

|

Business services |

1.4 |

7.5 |

|

Other services |

0.3 |

0.9 |

ASEAN has one of the highest

The “noodle bowl”4 of trade agreements signed by ASEAN in recent years with China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand strengthen the functioning of the Asian value chain and act to divert trade away from India.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is being negotiated by all the countries in ASEAN. India, Japan, Korea and China are also a part of it. On completion, it would account for 40% of world trade. However, the overlap of membership between TPP and RCEP would affect India-ASEAN trade. First, a successful TPP would set increased quality standards

The ‘Make in India’ initiative in conjunction with the recently implemented investment agreement between India and ASEAN should help chisel Indian policies to facilitate India’s integration in the Asian value chain in sectors like electronics, gems and jewellery, automobiles and pharmaceuticals5. The first three are sectors which have the longest and

The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) will transform ASEAN into a region with free movement of goods, services, investment, skilled labour and capital. This is particularly relevant for the CLMV nations (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) promising equitable development6. The free mobility of labour within the AEC region might hamper India’s prospects in terms of mobility of skilled workers, which has just been implemented with the India-ASEAN Services agreement7. It could also choke out some of the investment that India might have obtained from the region due to

ASEAN imports services to the tune of US$300 billion (ASEAN, 2013). Trade in services like information technology (IT), business services and IT-enabled services are areas of strength for India. ASEAN countries like

Conclusion

While we recognise that the ASEAN-India economic relationship has grown remarkably starting 2002, there is immense potential to grow the relationship further through both trade and investment and by India integrating into the Asian value chain.

Industries like automobiles, gems and jewellery have seen some integration between India and ASEAN nations. The recently implemented investment agreement along with the ‘Make in India’ initiative should help such integration, targeting sectors like electronics and pharmaceuticals. India’s trade advantage as an exporter of professional services and IT-related services should see greater exports with the implementation of the services agreement.

Given the above opportunities, India might face challenges due to the existing “noodle bowl” of trade agreements and mega RTAs which facilitate ASEAN trade in GVCs. The effects of TPP and RCEP would require greater commitments which India would need to abide by, for entering the value chain. The current culture of reticence towards FTAs in India acts against prospects of integrating with value chains. The formation of the AEC could further erode India’s opportunity by allowing free flow of skilled labour and capital within the ASEAN region. Agreements reached at the RCEP would crucially determine India’s future trade and value chain integration with ASEAN.

Notes:

- In a major shift away from policies of the Cold War era, India adopted the “Look East” Policy soon after economic liberalisation in 1991 to increase economic and commercial ties with East and Southeast Asian nations such as China. Over the years the policy has also concentrated on building closer ties on the strategic and security aspects in the region.

- The India-ASEAN FTA is an agreement between India and the ASEAN countries including Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The FTA reduced tariff barriers to trade between India and the ASEAN countries, and included specific provisions for services trade and investment facilitation.

- Allocative inefficiency refers to a situation where the value paid to resources deployed in production of a commodity does not match the marginal price of the commodity, leading to a welfare loss. It implies that the resources could be better utilised elsewhere.

- First coined by Jagdish Bhagwati, the term “noodle bowl effect” or “spaghetti bowl effect” refers to the overlapping trade rules which East and Southeast Asian economies have committed themselves to, by signing multiple trade agreements with various countries. For a better understanding, one may refer to ADB (2013).

- The investment chapter of the India-ASEAN FTA was signed in September 2014 laying down rules with rest to foreign direct investment (FDI) in ASEAN countries by India and vice versa.

- The AEC has been conceptualised by the ASEAN country governments and is yet to be implemented. The community would facilitate intra-ASEAN trade and investment. The less developed members of the ASEAN group would benefit due to

easier flow of capital and labour across ASEAN countries. Investorsof high-cost countries would find it easier to invest in the developing countries. Thus, equitable development could be achieved. See http://www.asean.org/storage/2015/12/AEC-at-a-Glance-2015.pdf - Since India is not a member of the proposed AEC, it would not get the benefits of the community when it is formed. India as a trade partner of the countries in the AEC and would thus be at a disadvantage as skilled workers from within the AEC would get preferential treatment.

- Trade in services through mode 4 involves Indian professionals travelling to the trading partner’s country to deliver services. This poses threats to

employment of professionals who are citizens of the trading partner. Hence mode 4 trade in services remains an issue where most of India’s trading partners negotiate cautiously and movement of Indian professionals abroad remains restricted.

Further Reading

-

ADB (2013), ´Asian Free Trade Agreements: Untangling the noodle bowl´, Asian Development Bank.

-

Baldwin, R (2006), ‘Globalisation: The great unbundling(s)’, Globalisation challenges for Europe, Helsinki: Secretariat of the Economic Council, Finnish Prime Minister’s Office.

- Bhattacharya, R and A Mandal (2014), “Estimating the Impact of the India-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement on Indian Industries”, South Asia Economic Journal, 15(1): 93-114.

- Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) (2011), ‘ASEAN+1 FTAs and Global Value Chains in East Asia’, ERIA Research Report 2010, No. 29.

- Goyal, T and A Mukherjee (2015),‘Creating a services value chain between India and Thailand’, Ideas for India, 8 July 2015.

- Kowalski, P, JL Gonzalez, ARagoussisand CUgarte(2015), ‘Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies’, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 179, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Ministry of External Affairs (2014), ‘Indian Exports to ASEAN to touch $280 Billion in 10 years: StanChart’, Weekly Economic Bulletin, ITP Division, MEA, Government of India, Issue No. 586, 1 September 2014.

- Nataraj, G and R Sinha (2013), ‘India ASEAN FTA in Services: Good for the region, very good for India’, East Asia Forum, Observer Research Foundation.

- Pal, Parthapratim and Mitali Dasgupta (2008), “Does a free trade agreement with ASEAN make sense?” Economic and Political Weekly, XLIII (46). Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40278168?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Press Information Bureau (2014), ‘India formally signs Trade in Services and Trade in Investments Agreement with ASEAN’, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, 9 September.

- Sikdar, C and B Nag (2011), ‘Impact of India-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement: A cross-country analysis using applied general

equilbrium modelling’, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 107. - Veeramani, C and Gordhan K Saini (2011), “Impact of ASEAN-India preferential trade agreement on plantation commodities: A Simulation Analysis”, Economic and Political Weekly, XLIV (10): 83-92. Available at: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/plantation%20commodities.pdf

10 March, 2016

10 March, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.