School closures during Covid-19 significantly impacted early childhood education, especially in households without sufficient parental engagement. Using data from households affiliated with Balwadis and preschools in Mumbai and Pune, Vernekar et al. find that those with access to a structured educational technology programme reported higher engagement levels. This effect was even greater for households that also received teacher support. They make a case for using such ed-tech programmes for blended schooling to minimise learning inequalities in case of future shocks.

Early childhood education (ECE), which is recognised as one of the most critical stages for children’s development over their lifetimes (UNICEF, 2020), received limited attention during the Covid-19 pandemic across the world. It may have been one of the least prioritised areas of well-being areas for children across all levels of education, owing to both institutions and households facing severe opportunity costs of devoting their time and resources to ECE. Even six months into the pandemic, only 60% of countries that had started remote learning, had done the same for ECE (UNICEF, 2020).

In India, schools and ECE centres, such as Anganwadis and Balwadis, remained shut for up to two years during the pandemic. Teachers and parents were forced to adapt to remote teaching and learning methods almost overnight. Closures of schools and increased reliance on education technology (ed-tech) further necessitated parental engagement and participation, especially with younger children at the ECE stage (Schroeder and Kelley 2009, Borup et al. 2014). In turn, the need to understand and address barriers to parental participation – such as lack of educational resources, time and cognitive bandwidth – which prohibited low-income parents from engaging with their children’s education even prior to the pandemic, became more prominent (Boulton 2008, Murphy and Rodríguez-Manzanares 2009, Liu et al. 2010).

While there is growing documentation on challenges faced by children and households in primary and secondary schools during Covid-19 closures1, this is limited in the context of ECE. Moreover, while there is growing evidence on the efficacy of low-tech interventions in resource-constrained contexts (Hohlfeld et al. 2010, Hollingworth et al. 2011), but little has been understood about how technology and teacher support might enable parental engagement, especially where necessitated by age of the child.

The study sample

In ongoing research (Vernekar et al. 2022), we aim to fill this gap by providing evidence on parental and student engagement in ECE in India, using data from a survey of 676 households and in-depth interviews with 58 teachers in Pune and Mumbai (urban Maharashtra) from April to June 2021. This period coincided with the peak of the second wave of Covid-19 in India.

The selected household and teachers were affiliated with Balwadis2, and preschools in Mumbai and Pune, run by Akanksha Foundation, a non-profit working with children from low-income households.

Both these sets of ECE centres were piloting a low-tech programme called E-Paathshala between January and June 2021. This was a digital intervention, run by Rocket Learning, a non-profit ed-tech organisation, that provides age-appropriate structured content for 3 to 8 year-olds through WhatsApp. The content, in the form of bite-sized videos of 2-3 minutes, was sent in Marathi or Hindi (depending on the medium of instruction of the centre) to a WhatsApp group comprising parents and teachers. The content targetted parents and was sent daily (other than during holiday periods), showcasing an educational activity only requiring materials easily available or procurable (like a spoon or flour). Teachers on WhatsApp groups were required to motivate parents to share videos and images of their children participating in the educational activity, and to provide feedback and acknowledge it through encouraging words and smiley-face emojis. Parents would also receive report cards every week indicating the number of activities completed by them and their children.

All Akanksha schools enrolled their children in this E-Paathshala programme. However, not all Balwadis had enrolled the children at the time of data collection. Teachers at both types of learning centres were providing educational and non-educational support to the parents. In Balwadis, this support – in the form of home visits, live classes, and following-up with parents regarding completion of activities, and ad-hoc support with procurement of medicines and ration – varied across centres and was relatively more unstructured than the support provided by teachers of Akanksha. The latter provided live classes at least twice a week, fortnightly ‘parent classes’ and more regular follow-ups with parents regarding the completion of activities. It also provided many forms of non-educational support through a dedicated ‘community-support network’, established prior to the pandemic. Members of the community-support network, along with teachers, regularly engaged in ‘well-being calls’ with parents to provide mental support and respond to any demands for ration, medicines or education materials in a structured manner.

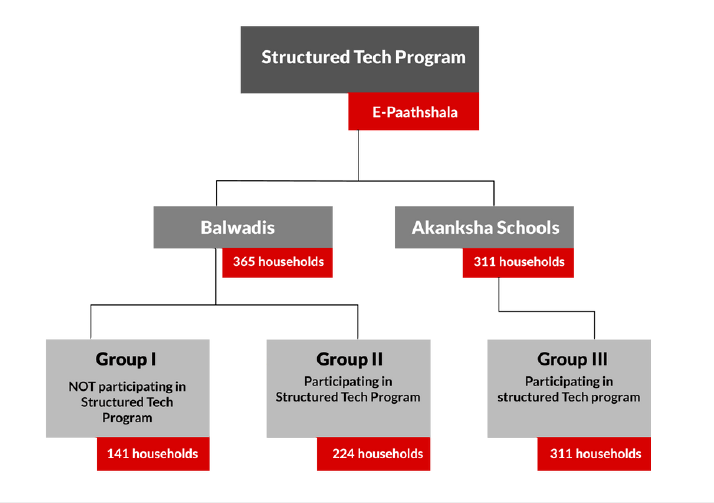

Our sample3 consists of those that received a mix of these interventions, and broadly resulted in three types of households that allow us to understand and disentangle experiences of parents with structured low-tech and teacher support compared to those who could not access it:

- Group 1 (141 households) included parents and children from Balwadis that neither accessed the e-Paathshala programme, nor the more structured teacher support programme

- Group 2 (224 households) included parents and children from Balwadis that were accessing the e-Paathshala programme but not the more structured teacher support programme

- Group 3 (311 households) included parents and children from Akanksha schools that were accessing both – the e-Paathshala programme and the more structured teacher support programme

The structure of our sample can be viewed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sample size and distribution

Household surveys and interviews with teachers were administered telephonically. From households, we captured details on social and economic characteristics, specific details about the sampled child, and detailed information about parental engagement with that child – including time spent on activities, comfort with the programme and the likelihood of continuing to participate in the programme. We also asked a few open-ended questions about their experiences with the programmes.

The teachers were asked detailed questions about their experiences with the structured tech programme, experiences and challenges in adapting to digital modes and how they supported parents during the pandemic-related disruptions.

Sample characteristics

While the sample does not represent the most disadvantaged4, the average household was still more disadvantaged than an average resident of urban Maharashtra (see Vernekar et al. (2022) for more details), especially compared to those in large cities like Mumbai and Pune, where they resided. About half the fathers were employed in daily wage work and/or skilled labour (for example, as electricians), and the majority of mothers who were engaging in paid employment did domestic work.

We find that economic status follows a gradient across the groups5 - Group 1 had the lowest median income (Rs.11,000), followed by Group 2 (Rs. 12,000) and then Group 3 (Rs. 15,000). This is similar for other characteristics such as ownership of assets (TVs, electronic devices, fridges). Therefore, while comparing parental engagement across all groups, we account for socioeconomic status, wards and cities of residence, incidence and age of the child’s siblings, and period of survey (whether coinciding with a holiday period or lockdown), among other factors, in a conditional regression framework6.

Impact of ed-tech programmes on parental engagement: what worked

We find that households which were participating in the structured ed-tech and teacher programmes (Group 2 and Group 3) were more likely to report receiving content on more days and reported higher parent and child engagement levels, compared to those in Group 1. Parents also expressed a higher willingness to continue participating in the ed-tech programme even after the lockdowns, compared to those in Group 1 who were not accessing the programme. We find this willingness to continue engagement was higher for those with relatively more educated mothers (who had completed grade 10 or above). Those also receiving structured teacher support (Group 3 households) had even higher engagement levels than the other two groups, and reported spending more time and number of days of engagement with the structured ed-tech programme.

In-depth interviews with teachers and open-ended questions asked to parents corroborated these findings and highlighted several factors that may have helped the programme increase engagement, such as type and structure of content, and resources and capacity demanded from both parents and children.

Teachers from both Balwadis and Akansha schools reported that the interactive and play-based nature of the content, and the various ‘nudges’ and feedback mechanisms incorporated in the ed-tech programme made parents more responsive. Teachers also attributed the programme's ability to drive engagement to how contextually appropriate it was – the content featuring an adult doing the activity with the child may have made it easy to understand, and activities only required materials that were usually easily available at home. The latter was also reflected in our survey, with more than 90% of parents reporting they had the required resources at home.

Teachers in Akanksha schools further spoke about the criticality of providing predictable and consistent non-educational support, which is likely to have helped and allowed parents to allocate more time to spend with their children. This, along with more structured teaching engagements such as providing fora like live classes and parent-teacher meetings to discuss the activities, may be why Group 3 households enrolled in their schools had even higher engagement levels than those in Group 2 who were only accessing the ed-tech programme.

Concluding thoughts

Based on a survey with parents and in-depth interviews with teachers, we find that participation in a structured low-tech programme and accessing more structured teacher support was associated with higher parental engagement levels. Moreover, teachers reported learning innovative teaching techniques for familiar concepts that aided them in their own practice. For those households that had digital devices, contextually appropriate content, that was adapted to the constraints of households and minimised the need for monetary or time investments, was able to drive engagement levels. The level of parent-child engagement is potentially augmented through provisioning of educational and non-educational support.

While school closures due to Covid-19 have ended, the models studied in this research provide meaningful insights in enabling sustained parental engagement, and strengthening resilience of households and the schooling system to future shocks and crises. In fact, the growing incidence of shocks such as seasonal climatic adversities and natural disasters, that lead to short-term school closures in various parts of India every year, reflect the importance of developing systems for blended modes of schooling. The benefit of ed-tech might especially be seen for students who are forced to be absent from school for prolonged periods – such as migrant children, or those who supplement farming work seasonally.

Addressing barriers that prevent parental engagement through educational and non-educational support programmes have the potential to minimise inequalities in learning gains between students from relatively better-off and worse-off backgrounds (Cunha 2006, El Nokali et al. 2010). Non-educational support delivered through dedicated resources developed for this purpose may protect households and schools from economic and other shocks that might otherwise force them to deprioritise educational investments.

While the role of teachers is critical in ensuring the success of such interventions, it cannot be realised without assessing and investing in the capacity of existing functionaries and institutions responsible for ECE provision. Disadvantaged households rely on Anganwadi centres for ECE, and in the current context, these centres remain under-resourced – especially with low instructional time allocated towards ECE (Ganimian et al. 2021). Further, government teachers and workers already face high administrative burdens and feel undervalued for their work (Ramachandran 2020). Anganwadi workers, in particular, are found to be underpaid and many continue to face several delays in getting their salaries and incentives (PTI, 2022).

These aspects must not be overlooked while designing programmes involving them: understanding and alleviating barriers faced by teachers and parents in under-resourced contexts is important to help design useful programmes.

Notes:

- See Vernekar, Rai and Singhal (2022) here for a summary of recent evidence on education-related surveys in India during Covid-19.

- Balwadis are dedicated centres for early childhood education, run by multiple non-governmental organisations through a public private partnership model with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), with the purpose of catering to low-income communities and areas of Mumbai where ECE delivery is lacking. As of July 2021, there are 819 balwadis, run by 25 different NGOs under this model.

- The break-up of our sample across cities and medium of instruction is as follows: we surveyed 676 parents (139 parents from 8 Akanksha schools in Mumbai; 172 parents from 9 Akanksha schools in Pune; and 365 parents from Balwadis in Mumbai); and 43 teachers from Balwadis (31 teaching in Marathi medium and 12 teaching in Hindi medium), and 15 teachers from Akanksha schools.

- In our sample, the reported median household monthly income was Rs. 12,000; about 70% of households had televisions with cable; and 48% of mothers and 56% of fathers had completed 10th grade schooling or above.

- Despite the ed-tech and teacher support programmes being targetted at low-income households, and through non-exclusionary admission, there are significant differences between socioeconomic indicators across the three groups, suggesting some sort of association of advantage that comes with access to the different educational programmes.

- See Vernekar et al. (2022) for more details on the sample, methodology and limitations.

Further Reading

- Borup, Jered, Charles R Graham and Jeffery S Drysdale (2014), “The Nature of Teacher Engagement at an Online High School”, British Journal of Educational Technology, 45 (5): 793-806.

- Cunha, F, JJ Heckman, L Lochner and DV Masterov (2006), ‘Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation’, In E Hanushek and F Welch (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education.

- El Nokali, Nermeen E, Heather J Bachman and Elizabeth Votruba-Drzal (2010), “Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school”, Child Development, 81(3): 988-1005.

- Ganimian, AJ, K Muralidharan and CR Walters (2021), ‘Augmenting State Capacity for Child Development: Experimental Evidence from India’, NBER Working Paper 28780

- Liu, Feng, Erik Black, James Algina, Cathy Cavanaugh and Kara Dawson (2010), “The Validation of One Parental Involvement Measurement in Virtual Schooling”, Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9(2): 105-32.

- Hohlfeld, Tina N, Albert D Ritzhaupt and Ann E Barron (2010), “Connecting schools, community, and family with ICT: Four-year trends related to school level and SES of public schools in Florida”, Computers & Education, 55(1): 391-405.

- Hollingworth, S, Ayo Mansaray, Kim Allen and A Rose (2011), “Parents' perspectives on technology and children's learning in the home: Social class and the role of the habitus”, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(4): 347-360.

- Murphy, Elizabeth and Maria A Rodríguez-Manzanares (2009), “Teachers’ Perspectives on Motivation in High School Distance Education”, International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 23(3): 1-24. Available here.

- PTI (2022), ‘Anganwadi Workers Protest Demanding Honorarium Hike; Delhi L-G to Meet Them on July 16’, The Hindu, 13 July.

- Ramachandran, Vimala (2020), “Government School Teachers in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 55(41): 7-8.

- UNICEF (2020), ‘UNICEF Annual Report 2019’.

- Schroeder, Valarie M and Michelle L Kelley (2010), “Family environment and parent‐child relationships as related to executive functioning in children”, Early Child Development and Care, 180(10): 1285-1298.

- Vernekar, NP, P Pandey, K Singhal, A Narayan Rai and A Reddy (2022), ‘Parental Engagement in Early Childhood Education During COVID-19: Learning from Structured Tech and Teacher Support Programs in Urban Maharashtra’, 37th IARIW General Conference.

- Vernekar, N, A Narayan Rai and K Singhal (2022), ‘Clearing the Air: A Synthesised Mapping of Out of School Children during COVID-19 in India’, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, 1 November.

03 April, 2023

03 April, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.