Soon after Aadhaar was made compulsory for availing midday meals in schools, the government claimed that the move had helped expose several instances of schools siphoning off funds under the scheme by reporting inflated student enrolment. Comparing official data with that from the Indian Human Development Survey, this column shows that corruption in the scheme is less than what is being alleged - and not of the nature that Aadhaar can check.

In Februrary 2017, Government of India issued a notification that effectively makes the unique identification (UID) number, or Aadhaar1, compulsory for children to avail midday meals (MDM) in schools. The move rests on the belief that Aadhaar can help check corruption in the MDM scheme. Soon after the notification was issued, media reports surfaced whereby the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) claimed that Aadhaar helped expose about 440,000 ‘ghost’ students in Jharkhand, Manipur, and Andhra Pradesh. The government maintains that striking off these fictitious beneficiaries will help arrest the siphoning of funds by reporting inflated attendance figures. In this column, I seek to investigate the claims made by the government about corruption in the scheme. Matching official MHRD data with data from another independent source (details below) suggests that corruption in the MDM scheme is not as much as the government thinks it might be.

How many school kids get midday meals?

In the recent media reports, it is alleged that many government schools have been showing non-existent students on their rolls to claim additional funds under the MDM scheme. It is important to note here that meals are served on the basis of daily student attendance rather than enrolment. But then one may claim that schools are inflating attendance numbers as well to siphon off funds.

A simple way to check this is to compare (A) the number of children actually being served MDM on ground, with (B) officially recorded numbers by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). For (A), I use India Human Development Survey (IHDS) 2011-12 which is a nationally representative independent household survey of villages and urban neighbourhoods. IHDS gives us estimates of the number of children in government, government-aided and EGS (Education Guarantee Scheme) schools at the primary and upper primary levels, who report whether they are fed at school.

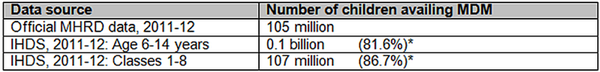

Now, for (B), according to MHRD data for the period of 2011-12, 105 million children availed MDM in all government schools at the primary and upper primary level, although there are 143 million enrolled children.

From the IHDS data, I calculate the proportion of children in the age group of 6-14 availing MDM in government schools. This turns out to be 81.6%. According to Census 2011 data, the number of children in the 6-14 years age group is 190 million. Further, according to IHDS, the proportion of students enrolled in government schools in the same age group is 63.8%. Combining this proportion with the total number of children in age group of 6-14 from Census data gives the total number of children in government schools in this age group. This is 122 million. Finally, combining this number with the proportion of children availing MDM in this age-group (81.6%) from IHDS gives the total number of children being served MDM. This turns out to be 100 million.

However, according to IHDS data, there are approximately 8.9% under- and over-age children in classes 1-8. This means that more children than those in the 6-14 age group are availing MDM. Therefore, as a further check, I use the enrolment in classes 1-8 in place of the total number of children in the 6-14 age group to take into account such children.

Using enrolment, the proportion enjoying MDM increases to 86.7%. According to IHDS data, the number of children in government schools in classes 1-8 is 123 million. Combining this with the proportion of children availing MDM in classes 1-8 (86.7%) gives the total number of children being served MDM, which is 107 million.

Since, by construction, the number of children being served MDM using the criteria of age, that is 0.1 billion is an underestimate, it is consistent with the number I get by using the criteria of class, which is 107 million.

Thus, according to independent data, the number of children enjoying MDM in government schools ranges between 100-107 million, which is more or less equivalent to the official number (105 million). This suggests that the schools are not inflating the number of children being served meals.

Table 1. Official number of children against actual number availing midday meals

*Percentages indicate the proportion of government school children availing MDM in the age group of 6-14 and classes 1-8 respectively in the IHDS Survey.

*Percentages indicate the proportion of government school children availing MDM in the age group of 6-14 and classes 1-8 respectively in the IHDS Survey. Concluding remarks

Corruption in the MDM scheme has been wildly exaggerated with no verified basis. We have seen that the actual number of children being served MDM on the ground is more or less equal to the official MHRD number. Moreover, quantity fraud, that is, giving children less than their entitlement is also likely to be small. Children and their parents expect a full meal and that is what official norms provide for (Khera 2006).

On the other hand, the benefits of the scheme have been well established and recognised. Research shows that school meals have resulted in substantial increases in primary school enrolment (Jayaraman and Simroth 2015). Additionally, Afridi (2011) finds that meals have also been effective in raising daily school participation rates, particularly among girls. Regular hot cooked food reduces classroom hunger and contributes to better child nutrition (Afridi 2010). The scheme also acts as a safety net for young children, especially so in the event of an external shock like drought (Singh, Park and Dercon 2014). All of this has been found to have a positive effect on learning achievements, with children improving their test scores by approximately 10-20% (Chakraborty and Jayaraman 2016).

Further, the scheme serves the important purpose of instilling values of social equity among children (Sinha 2008). Daily meals provide children the opportunity to sit together and eat, breaking away from the barriers of caste and class. It is also a valuable source of dignified employment for more than 2 million disadvantaged women, as cooks and helpers (Drèze, Khera and PEEP team 2014).

All this is not to deny that there are no problems with the scheme. The real challengesimpeding it are faulty implementation mechanisms (Drèze and Goyal 2003). For instance, there is a lack of safe storage and cooking spaces, menus are in need of revision, funds and supplies are not released in a timely manner, etc. Such shortcomings in the scheme cannot be addressed by a blind focus on Aadhaar.

This article builds on remarks made by Jean Drèze in a recent NDTV debate. The author would also like to thank Reetika Khera for her invaluable insights and comments.

Notes:

- Aadhaar or Unique Identification number (UID) is a 12-digit individual identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) on behalf of the Government of India. It captures the biometric identity – 10 fingerprints, iris and photograph – of every resident, and serves as a proof of identity and address anywhere in India.

- India Human Development Survey (IHDS) is a nationally representative, multi-topic survey jointly organised by researchers from the University of Maryland and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi.

Further Reading

- Afridi, Farzana (2011), “The Impact of School Meals on Student Participation: Evidence from Rural India”, Journal of Development Studies, 47(11):1636-1656.

- Afridi, Farzana (2010), “Child Welfare Programs and Child Nutrition: Evidence from a Mandated School Meal Program in India”, Journal of Development Economics, 92(2):152-165.

- Chakraborty, T and R Jayaraman (2016), ‘School Feeding and Learning Achievement: Evidence from India’s Midday Meal Program’, Discussion Paper 10086, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

- Das Gupta, M and N Pandey (2017), ‘Midday meal scheme: Aadhaar exposes 4.4 lakh ‘ghost students’ across 3 states’, Hindustan Times, New Delhi, 26 April 2017.

- Drèze, J, R Khera and PEEP team (2014), ‘A PEEP at another India’, Survey report, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. Available here.

- Drèze, Jean and Aparajita Goyal (2003), “The Future of Mid-day Meals”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, Issue No. 38, pp. 4673-4683.

- Jayaraman, Rajshri and Dora Simroth (2015), “The Impact of School Lunches on Primary School Enrollment: Evidence from India’s Midday Meal Scheme”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(4):1176-1203.

- Khera, Reetika (2006), “Mid-Day Meals in Primary Schools: Achievements and Challenges”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, Issue No. 46.

- Khera, R (2017), ‘Feeding Insecurities’, Hindu Business Line, 31 March 2017.

- Ministry of Human Resource Development (2017), ‘Notifications under Section 7 of the Aadhaar Act, 2016 for Mid Day Meal Scheme’, Department of School Education and Literacy, Government of India, 7 March 2017.

- Singh, Abhijeet, Albert Park and Stefan Dercon (2014), “School Meals as a Safety Net: An Evaluation of the Midday Meal Scheme in India”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 62(2):275-306.

- Sinha, Dipa (2008), “Social Audit of Midday Meal Scheme in AP”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 43, Issue No. 44. Available here.

31 July, 2017

31 July, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.