Newspapers are an important source of political information for Indian voters. This article looks at how political factors influence the newspaper market. Using the announcement of delimitation in the mid-2000s as an exogenous shock, it finds that there was an increase in newspaper circulation in districts whose electoral importance increased after the announcement. It notes that, in the short run, this change was driven by a shift in supply, as voters were still unaware of the political shock.

Information from the media matters for all sorts of political outcomes, including who gets elected, how resources are distributed, and what issues become particularly salient (see Besley and Burgess 2002, Strömberg 2004, Gentzkow 2006, George and Waldfogel 2006, Snyder and Stromberg 2010, Gentzkow et al. 2011, Gavazza et al. 2019). The amount and type of information that voters are exposed to is therefore of huge political significance. However, we know very little about the determinants of this exposure to information, and in particular, about its political determinants. To what extent does the overall media market itself depend on political factors?

Studying the relationship between political factors and the news market is not straightforward, given all the factors that shape the development of the media market – most of which are hard to capture empirically. Furthermore, political actors are unlikely to be forthcoming about how they seek to influence the news. In a working paper (Cagé, Cassan and Jensenius 2023), we build an original dataset on Indian newspapers and leverage the state-wise announcement of the new delimitation of the mid-2000s to causally identify the impact of one major change in the political environment on newspaper markets across India: the change in the relative electoral importance of administrative districts.

The newspaper market in India

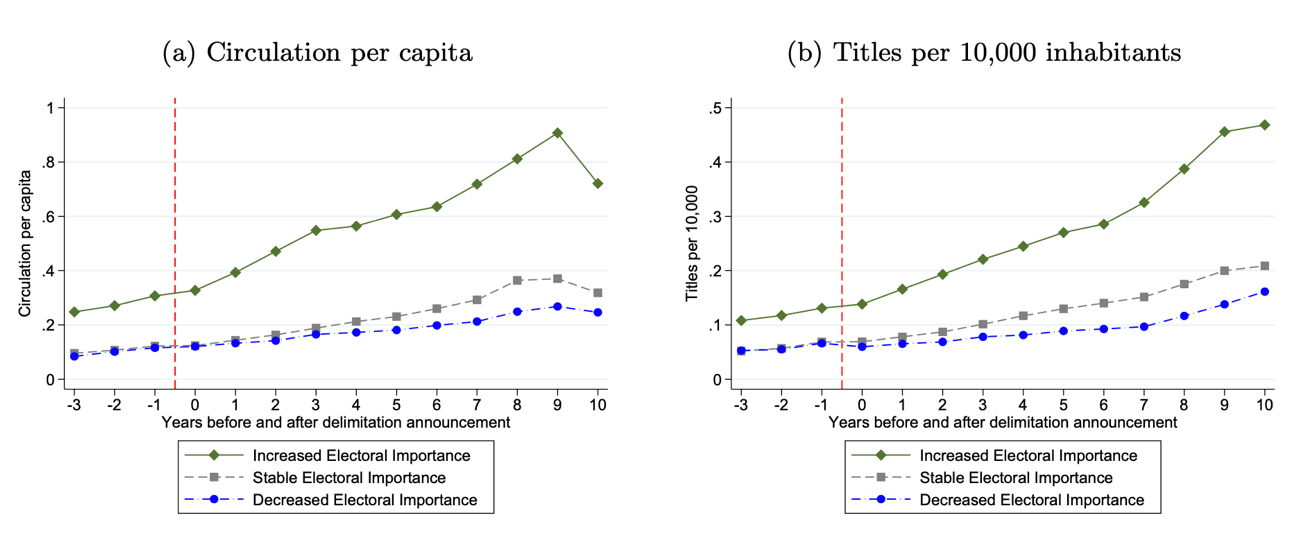

Newspapers are an important source of political information in India. Other media, such as radio, TV, and social media, are also important, but a large share of the Indian electorate regularly reads newspapers (Media Research Users Council, 2017). And India has, by far, the largest newspaper market in the world – according to the Office of the Registrar of Newspapers, there were more than 118,000 newspaper publications in India in March 2018, and in 2017-2018, the total circulation of the registered publications in India was 430 million (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scale of the newspaper market in India

With such vast readership, it is no surprise that the newspaper industry in India is big business. According to Kohli-Khandekar (2013), the top newspaper groups in India have operating margins upwards of 25%. In 2018, print advertising generated revenue of Rs 210.6 billion (Indian Brand Equity Foundation, 2018), and the overall print industry revenue was Rs 218.9 billion. However, there is considerable evidence that actors also enter the newspaper market for non-monetary benefits like political influence: Jeffrey (2000) argues that “people of influence” acquired or founded newspapers to seek influence over bureaucracies and politicians. In a report from 2013, the Telecom Regulatory Authority concluded that “there is an increasing trend of influence of political parties/politicians in the media sector.”

To be able to study how local-level media markets have evolved with changes in the political environment, we built a dataset of newspapers from yearly reports published by the Registrar of Newspapers for India (RNI), that we digitised, cleaned and merged with census data and political data. This yearly governmental publication includes information on the universe of Indian newspapers, including their place of publication, circulation, language, and ownership. Our data includes information about the total number of newspapers and their circulation per capita for Indian districts between 2002 to 2017. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale and micro-level dataset on newspapers for any developing country.

The delimitation as an exogenous shock

To estimate the effect of electoral importance on newspaper markets, we leverage the announcement of the new delimitation of Indian electoral constituencies in the mid-2000s. The new constituency borders were drawn by the Delimitation Commission and although the final delimitation report was published in 2007, the state-wise draft delimitation reports were announced separately for each state between 2005 and 2007 – several years before the general or state elections were held.

The constituency borders were drawn out by the Delimitation Commission based on census figures. Importantly, there is no evidence of political interference in the delimitation exercise (see Jensenius 2013, Iyer and Reddy 2013). It was only when drafts of the new delimitation were publicly circulated that the new electoral incentives would have become evident to politicians and stakeholders such as media owners. For the general public, the implications of the changes probably became apparent only at the time of the next elections, which were still several years away at the time the draft delimitation was circulated.

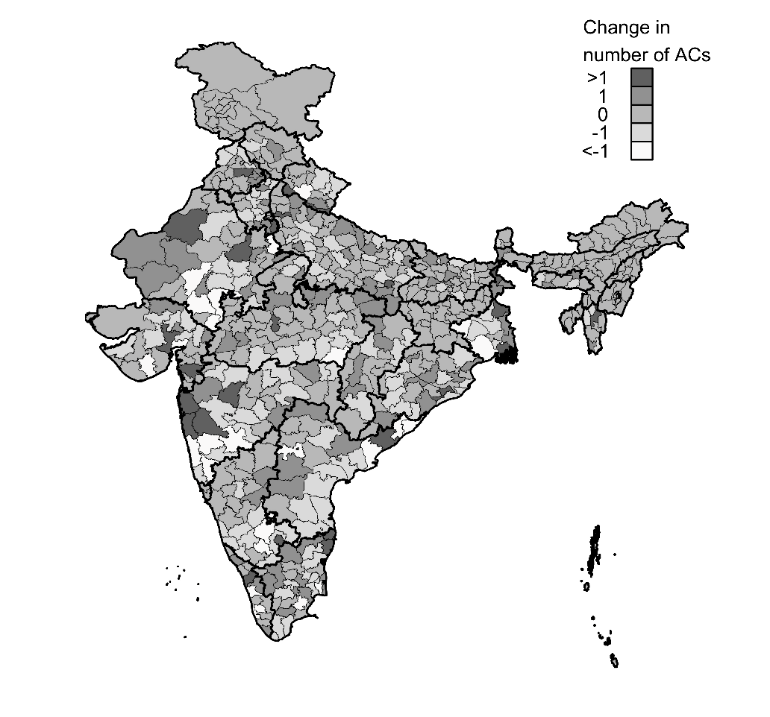

The delimitation did, however, have an important impact on the electoral importance of Indian administrative districts. Figure 2 shows the changes in the number of electoral constituencies, which has implications for the number of MLAs elected from each Indian district as a result of the delimitation: some districts lost one or several constituencies and others gained some. The publication of the state-wise draft delimitation reports can therefore be considered as an exogenous shock to the electoral importance of administrative districts. Because all other determinants of media consumption – like changes in the population or education level in the districts – are moving slowly over time, this sudden change in the electoral importance of a district allows us to isolate the causal effect of changes in electoral importance on the district-level supply of news media.

Figure 2. Change in number of state assembly constituencies in districts as a result of the delimitation

Main findings

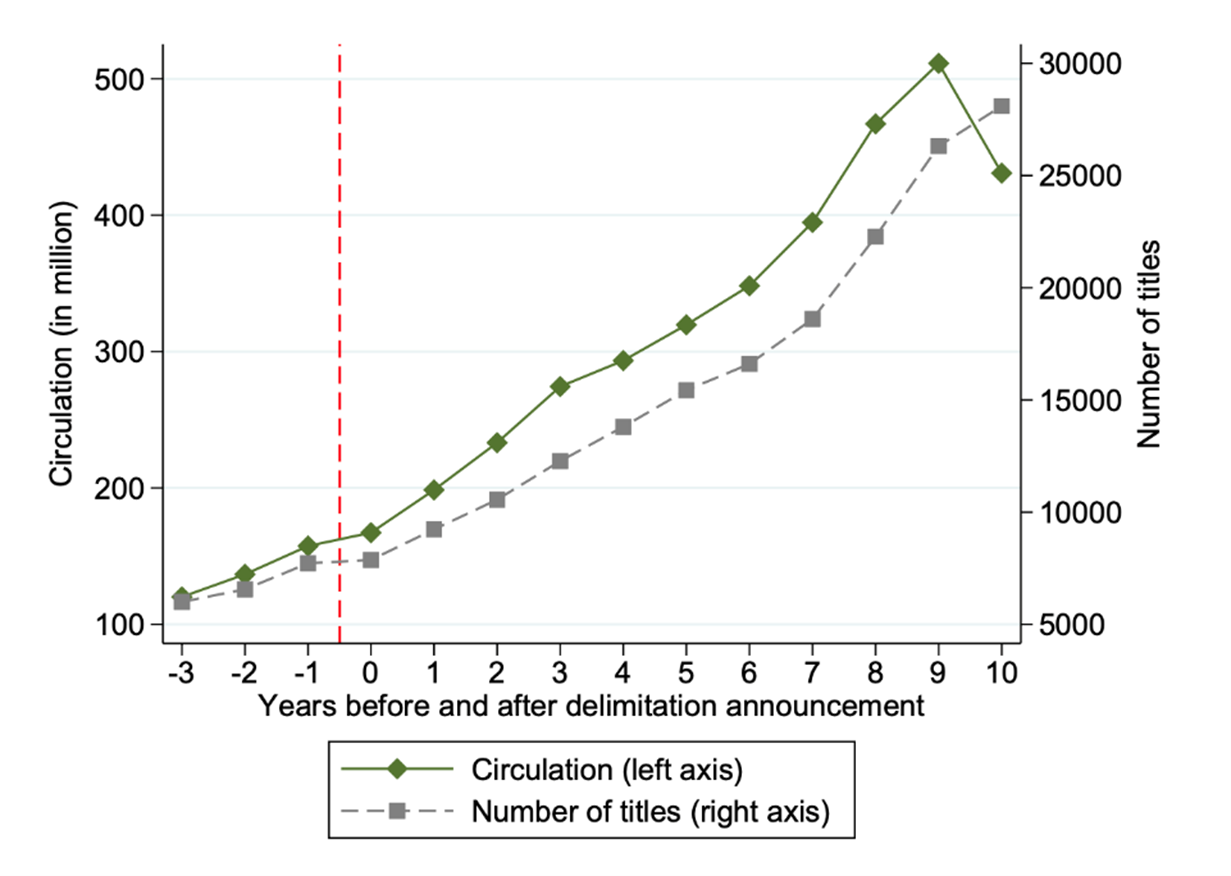

Our data, which cover most Indian districts between 2002 to 2017 (we exclude the few states that did not have a delimitation at the time), reveals a newspaper market in rapid growth. And, as we show in Figure 3, the growth was stronger in districts that would become more electorally important after the announcement of the delimitation than in other districts.

Figure 3. Evolution of media markets in districts of increasing and decreasing electoral importance after delimitation

Notes: (i) The figures present the evolution of circulation and the number of titles in India, decomposed between markets (districts) whose electoral importance increase, decreases, or remains stable over time. (ii) The red line indicates the time of the announcement of the delimitation. (iii) The data covers only 14 years in which all states are observed with the same time to announcement.

Source: RNI reports and authors’ computation.

This pattern holds even when we include various controls to rule out alternative explanations. In particular, we use an event-study approach (which compares the annual trajectory of the district whose electoral importance increases to that of other districts before and after the announcement of delimitation) and a difference-in-differences estimator (which compares districts whose electoral importance increases to that whose electoral importance does not, before and after the announcement of delimitation). As both methods include state-year and media market fixed effects, the effect of the state-level electoral cycle and that of fixed market-level characteristics are accounted for.

The documented increase is both statistically significant and economically important: according to our estimates, news markets whose electoral importance increased saw a substantial increase in newspaper circulation (by a third of a standard deviation). Furthermore, whereas media markets are obviously affected by factors other than electoral importance, we estimate that 12% to 18% of newspapers’ circulation in India after delimitation is due to this change in electoral importance.

We also show that the magnitude of the estimated effects varies with both political competition (measured before the delimitation) and the characteristics of newspapers and their owners. Using different measures of political competition (turnout, margin of victory and the effective number of political parties), we show that the effect is stronger in markets characterised by weak electoral competition before the delimitation – places where there is more scope for political mobilisation. We also show that the effect is stronger for local-language newspapers, which are more likely to cover local politics.

We also explore whether it is supply or demand that drives the changes in the documented outcomes. Our estimates indicate that in the short to medium run, the change in equilibrium is due to a shift in supply. This makes sense: as discussed above, in the short run, the political shock has been announced but is yet to be implemented, so readers are unlikely to be aware of it. In the long run, however, when the change in the political environment becomes visible to newspaper readers, demand becomes an important contributor as well. But crucially, our results indicate that even in the long run, demand cannot fully explain the increase in the number and circulation of newspapers; owners’ political motivations also seem to play a part in determining the news market equilibrium.

Conclusion

Consistent with qualitative evidence of a highly politicised newspaper media market in India, we find a substantial increase in the supply of newspapers in areas that gained electoral importance due to the delimitation. We document an increase in both the number of newspapers and the newspaper circulation in markets that gain electoral importance. This increase is almost immediate, even though elections were still several years away in most places, and continues over the ten-year period we look at after the delimitation announcement.

Our results have important implications for understanding voting behaviour and the overall quality of democratic processes. This is far from a complete picture of the extent to which India’s media market is politicised, but rather one clean example of the extent to which it reacts to changes in the political environment. When not just the content but also the size of the media market itself is so responsive to political factors, we are faced with a reality where different voters have drastically different starting points in their journey to becoming active and engaged citizens.

Further Reading

- Besley, Timothy and Robin Burgess (2002), “The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness: Theory and Evidence from India,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4): 1415-1451.

- Cagé, J, G Cassan and FR Jensenius (2023), ‘Electoral Importance and the News Market: Novel Data and Quasi-Experimental Evidence from India’, Available at SSRN 4364254.

- Gavazza, Alessandro, Mattia Nardotto and Tommaso Valletti (2019), “Internet and Politics: Evidence from U.K. Local Elections and Local Government Policies”, The Review of Economic Studies, 86(5): 2092-2135.

- Gentzkow, Matthew (2006), “Television and Voter Turnout,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(3): 931-972.

- Gentzkow, Matthew and Michael Sinkinson (2011), “The Effect of Newspaper Entry and Exit on Electoral Politics,” American Economic Review, 101(7): 2980-3018.

- George, Lisa M and Joel Waldfogel (2006), “The New York Times and the Market for Local Newspapers,” American Economic Review, 96(1): 435-447.

- Indian Brand Equity Foundation (2018), ‘Media and Entertainment’, Technical Report.

- Iyer, L and M Reddy (2013), ‘Redrawing the Lines: Did Political Incumbents Influence Electoral Redistricting in the World’s Largest Democracy?’, HBS Working Paper Series.

- Jeffrey, R (2000), India’s Newspaper Revolution: Capitalism, Politics and the Indian-language Press, 1977-99, Hurst.

- Jensenius, Francesca (2013), “Was the Delimitation Commission Unfair to Muslims?”, Studies in Indian Politics, 1(2): 213-229.

- Kohli-Khandekar, V (2013), The Indian Media Business, SAGE Publications.

- Media Research Users Council (2017), ‘Indian Readership Survey’, Technical Report.

- Snyder, James M and David Strömberg (2010), “Press Coverage and Political Accountability,” Journal of Political Economy, 118(2): 355-408.

- Strömberg, David (2004), “Radio’s Impact on Public Spending,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1): 189-221.

- Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (2013), ‘Consultation Paper on Issues relating to Media Ownership”, Consultation Paper No.01/2013.

23 November, 2023

23 November, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.