In the previous part of the series, Dr Pronab Sen presented a pathway to recovery, focusing on the ‘survival’ phase, that is, the three-month period of lockdown. In this part he discusses the revival phase – four-month period after the lockdown is lifted and normal economic activity is allowed to resume from June 2020, and the recovery phase thereafter.

The revival phase

The next stage begins as the lockdown is lifted and normal economic activity is allowed to resume from June 2020, and should last about four months. At this point, all production entities will require significant additions to their working capital to resume production. Unfortunately, almost all of them by now will have hit their working capital limits and would have borrowed additionally to keep afloat. The FIs will be reluctant to increase these limits for the weaker and smaller entities. Again there is a strong case to be made for a mandatory increase (say doubling) of the working capital limits for all existing standard loan accounts. This can easily be accommodated by the banks since they will be flush with funds and there will be virtually no demand for fixed capital loans. However, in this case there may be large losses arising from loans being taken without the ability to service them, and the government will have to backstop this process by guaranteeing any erosion in the capital base of the FIs through recapitalisation or other means.1

This is the point at which the principal constraint starts shifting from supply to demand. Demand stimulus needs to begin in right earnest since producers will need to see credible evidence of demand for their goods and services before they resume operations. Commodity producers in particular will wait and see until their inventory holdings start coming down steadily. However, care needs to be taken to ensure that the stimulus is not overdone since production recovery will be relatively slow. By now considerable damage would have occurred to both the production and supply chain systems, and these would need to rebuild themselves before the real recovery phase starts. Many prices will have to be renegotiated and contracts redrawn. Labour will need to be persuaded to return to work, which will not be easy since the fear of infection will continue practically unabated. In a situation of this kind, excessive fiscal stimulus will quickly run into a supply constraint and trigger off inflation.

Income support through Jan Dhan accounts will also have to be continued during this period, but possibly at a somewhat lower level in rural areas. Additional income support should be provided through a substantial up-scaling of MNREGA2. The May package does contain an additional allocation of Rs. 0.4 trillion for this purpose. The main problem in doing so is that 40% of the costs of MNREGA works are borne by state governments, and these are all upfront costs.3 As has already been mentioned, state government budgets are already seriously stressed and will get worse going forward. It is extremely doubtful that they would be able to ramp up MNREGA works to the scales needed by the crisis. Therefore, the sensible thing to do would be for the Centre to pick up at least the materials costs until such time as the states’ fiscal position improves.

However, the MNREGA route will be of consequence only to rural workers and those migrant workers who have managed to return to their villages. The bulk of the unemployed, however, will continue to be in urban areas, and there is no workfare programme which can address their needs. Therefore, the income support programme will need to continue at the higher level for urban Jan Dhan accounts of the unemployed. Thus, the outlay on this account may reduce to not lower than around Rs. 0.08 trillion per week over this period, which can last for up to four months after lifting of the lockdown.

Thus, if all the elements of demand support are added up, the total for this four-month period comes to about Rs. 2.5 trillion, including the fiscal support contained in the May package. But even with this order of fiscal support and the liquidity provisioning by the RBI, primary damage to the economy will continue for two distinct reasons. First, a part of the production capacity would have already closed and will not be revived. Second, frictional problems (including return of migrant workers) with production revival will delay the process of ramping up production in the surviving enterprises. Both these factors are difficult to assess at this stage, but the magnitudes involved will need to be estimated for determining the eventual size of the fiscal support package.

There are, therefore, three steps that the government needs to urgently take up during this period. First, it is imperative that the government announces at least the minimum dimensions of the proposed demand support package at this time, even though the actual spend will happen later. Otherwise producers will be reluctant to bear the costs of starting up since they may not see the demand at the end of the road. This then causes a “chicken-and-egg” problem since producers will wait to see demand, but demand will not be created until production resumes and new incomes are generated.

Only the government can break this logjam by assuring adequate demand support. Since the estimated primary damage in the first two months is Rs. 20 trillion, the announced fiscal support to demand should be at least Rs. 10 trillion (including the Rs. 5 trillion provided through income support and clearing of outstanding dues) in 2020-21 itself, with assurance of more to follow if circumstances so demand.4 The bulk of the remaining Rs. 5 trillion for the remainder of the year should be in direct government expenditures on goods and services (including MNREGA) since this has a higher multiplier than simple income support, although it may take longer to implement on the ground.

At this point a word of caution is called for. Indian businesses across the board have been demanding tax cuts as a part of the fiscal stimulus. This is self-serving and must be resisted. The government has already given a sizeable cut in corporate income taxes in September 2019, and anything more is unnecessary. Moreover, cuts in personal income taxes benefit only a very small and affluent class of people, who are also the least affected by the lockdown. This would, however, reduce government tax receipts and constrain its ability to support the poor and the unemployed who need it the most.

The second step is to carefully track the process of recovery since, as has been mentioned, this will determine the total magnitude of the primary damage. The GST data should prove invaluable in estimating the proportion of enterprises which restart at any point in time and also the value of transactions that they undertake. This should provide sufficient information to compute the pace at which income generation is being restored and how much residual damage continues to occur. The GSTN5 should be charged with this task so that the government can track progress practically on a daily basis.

The third step is for all government Ministries/Departments to be charged with preparing projects and schemes in their respective jurisdictions and obtaining all necessary approvals so that a shelf of projects is available to government for actual funding once the recovery phase starts. Unless this is done, as we know from experience, the actual expenditures will get delayed and further damage will take place.

The recovery phase

Up to this point, the fiscal requirements are not that large. All the heavy lifting would have been done by the financial sector and state governments. However, once economic activities, particularly production, are ready to take off, the central government will have to step in with a large and sustained fiscal stimulus of the classical variety.

By this time, the aggregate loss of incomes would have become much larger, possibly more than Rs. 20 trillion (10% of GDP). Moreover, most households would have seen significant erosion in their savings. As a result, even though fresh income streams may come on line, households will first try to rebuild their asset base. Thus, production activities will be constrained by insufficient demand, and the government will have to lead the recovery process. Again, this should not be a large, ‘big bang’ intervention. If all goes well, the multiplier process should now be functional since supply responses can happen, and the government will have to build on this by calibrated, but sustained, fiscal expansion over the next three years or so in order to bring the economy back to some semblance of normality.

If, in the current year, such additional government expenditure (including expenditures by state governments) is Rs. 10 trillion, then the total GDP loss for the year could possibly be contained to around Rs. 10 trillion or a growth rate of -5.7%. The reason why the loss will be more than half of the primary damage despite fiscal support being more than half is that the damage is front-loaded while the fiscal support will be back-loaded. As a result, the multiplier effects will not be symmetric, leading to such an outcome.

The recovery phase does not end here. Even after the Rs. 10 trillion fiscal stimulus in 2020-21, the residual damage that will play out in 2021-22 will be at least Rs. 26 trillion. The remaining multiplier effect of the 2020-21 fiscal stimulus could be around Rs. 12 trillion and the growth momentum about Rs. 10 trillion, which will still leave a hole of Rs. 4 trillion to be filled in the 2021-22 budget. Experiments with the model suggests that to avoid negative growth in 2021-22, the government will have to implement a minimum fiscal stimulus of Rs. 14 trillion or 7% of GDP in 2020-21.

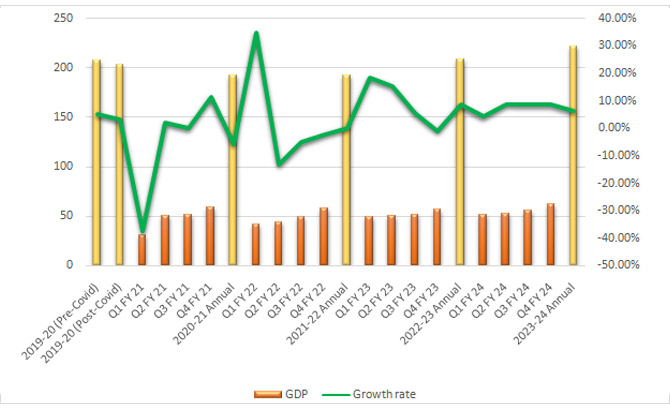

As an alternative for covering this gap, the government can continue with the fiscal stimulus in 2021-22 amounting to at least Rs. 2.6 trillion (at 2019-20 prices) over and above the expenditure plan contained in the 2020-21 Budget. The time-path of GDP with this option is given in Figure 1. As can be seen, with this strategy the GDP growth in 2021-22 would be flat (that is, 0%). It will also lead to regaining the 2019-20 level of GDP in 2022-23 and returning to a growth path of 6% thereafter. Restoration of the fiscal consolidation process can begin only after that.

Figure 1. GDP trends with stimulus in 2020-21 and 2021-22

However, these projections (and those in Figure 1 in Part II of the series) do not take into account two important dimensions that are endogenous to the recovery process and cannot easily be addressed in macroeconomic models such as this.6 The first is the distributional changes that will occur in the economy, which will lead to changes in aggregate savings-consumption behaviour. The clues to what these may be are to be found in the demonetisation episode. It seems almost inevitable that income distribution in the country will become even worse than it is today.7 As a result, the formal sector will recover rapidly and the MSME sector will be in dire trouble, which will perpetuate and probably steadily worsen the distributive asymmetry over time. As a result, consumption growth will be lower than has been assumed in the model on the basis of historical trends and, as a result, the multiplier will become progressively weaker. This can only be corrected by the government continuing the fiscal stimulus for a longer period in expenditures that directly help smaller firms in labour-intensive activities, such as MNREGA, rural roads, minor irrigation, low-cost housing, etc.

The second is that the model assumes that the production capacity of the economy remains unimpaired over the entire process. The moratorium and various liquidity support measures announced by the RBI and the government are designed to address this issue. However, as has already been mentioned, a fair amount of damage would have happened already, and more can be expected in the course of the current year until the full effects of the enhanced stimulus play out in 2021-22. Therefore, regaining the 2019-20 level of GDP in 2022-23 may not actually happen simply because of non-availability of production capacities unless sufficient private investment takes place during this full period. Sadly, this appears unlikely.

In the previous two parts of the series, Dr Pronab Sen presented a pathway to recovery from the Covid-19 shock in three distinct phases – survival, revival, and recovery. In the final part of the series, he discusses the financing of the recovery, addressing concerns around deterioration of the government’s fiscal position, and how resources can be raised for financing a larger stimulus package.

Notes:

- In the case of public sector banks (PSBs) this problem can be handled by a process of steady recapitalisation. For private FIs, however, it will have to be through 100% guarantees of such mandated loans, unless the government is willing to implement some variant of TARP (Troubled Assets Reconstruction Program) implemented by the US government in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

- Up-scaling will not only involve a large increase in the volume of works taken up, but also increase

in the number of days of work per household from the present limit of 100 per year to at least 150.

But this can happen only when the central government permits such work.. - In MNREGA, all costs relating to land, capital, management and materials are by states. The Centre only pays the wages, and that too ex post facto.

- Ideally the demand support should be much larger, but there are limitations on how much the government can spend in such a short period of time due to inherent rigidities in government processes and procedures.

- The Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) is a quasi-government agency that manages all GST transactions and is the custodian of the data.

- These are over and above the model assumptions discussed earlier.

- Post-demonetisation, the real wage rates dropped sharply. In the model it has been assumed that real wages remain constant.

ANNEXURE

Table 1. GDP trends with stimulus in 2020-21 and 2021-22

|

|

GDP (Rs. Tr. 19-20 prices) |

Growth rate (year-on-year) |

|

2019-20 (Pre-Covid) |

207.1 |

5.0% |

|

2019-20 (Post-Covid) |

203.4 |

3.0% |

|

Q1 FY 21 |

30.8 |

-37.5% |

|

Q2 FY 21 |

50.1 |

2.0% |

|

Q3 FY 21 |

51.7 |

-0.1% |

|

Q4 FY 21 |

59.2 |

11.2% |

|

2020-21 Annual |

191.8 |

-5.7% |

|

Q1 FY 22 |

41.4 |

34.7% |

|

Q2 FY 22 |

43.6 |

-13.2% |

|

Q3 FY 22 |

49.0 |

-5.2% |

|

Q4 FY 22 |

57.9 |

-2.3% |

|

2021-22 Annual |

191.9 |

0.0% |

|

Q1 FY 23 |

49.0 |

18.3% |

|

Q2 FY 23 |

50.2 |

15.3% |

|

Q3 FY 23 |

51.6 |

5.5% |

|

Q4 FY 23 |

57.3 |

-1.0% |

|

2022-23 Annual |

208.2 |

8.5% |

|

Q1 FY 24 |

51.0 |

4.1% |

|

Q2 FY 24 |

53.0 |

8.6% |

|

Q3 FY 24 |

55.2 |

8.5% |

|

Q4 FY 24 |

61.8 |

8.5% |

|

2023-24 Annual |

221.0 |

6.2% |

08 June, 2020

08 June, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.