Social science literature shows that women promote household welfare more than men. This column examines if consumption choices of husbands and wives change, depending on whether they have to work to earn the money that they are spending. It is found that wives’ preferences for joint household consumption remain largely independent of whether they work to earn the money, or receive it without working.

An unequivocal picture of women being more altruistic than their male counterparts in the family emerges from social science research (Quisumbing and Maluccio 2000, Udry et al. 1995, Datt and Joliffe 1999, Datt et al. 1991, Cross 1999). The women in the household appear to provide stronger patronage to overall family welfare, and promote joint household consumption more than men. Such observations provide a clear direction towards endowing women in the household with a greater decision-making role to foster and improve family welfare (Kabeer 1999). In a recent article in the India Blog of New York Times, “Are Men Useless? (Government Says Yes)”1, it is noted that some developing countries have already started to show a purposeful shift towards identifying women as the primary decision-makers in targeted welfare policies.

We hypothesise that the observed gender differences in altruistic choices in the household can possibly be due to differences in feeling of entitlement along with associated bargaining powers. Changes in feelings of entitlement can possibly come from factors such as receiving income with or without effort. Consequently, varying the sense of entitlement can possibly lead to different consumption choices and associated welfare outcomes for the family.

Surprisingly, there is very little work that examines the effect of changes in entitlements on demonstrated altruistic choices in the household. Since husbands and wives can have different economic roles due to historical reasons, social conventions, or current economic conditions, it begs the question whether altruistic choices among men and women (as household partners) are affected by differences in feelings of entitlement. In particular, can earning with or without effort influence consumption choices made by husbands and wives? This can be particularly significant now since increased opportunities to participate in the labour market have been rapidly changing the economic positions of women in the household. We evaluate whether feelings of entitlement differ based on income earned with or without effort, and whether such changes influence consumption choices in the household (Dasgupta and Mani 2013a, 2013b).

The experiment

We conducted an artefactual field experiment in New Delhi, India. Given our interest in observing decision-making in the household, our subjects comprised married couples only. 210 married couples participated in the experiment. The subjects were recruited from Bhogal, a prominent resettlement colony in South Delhi.

We introduced a novel allocation game to investigate whether income received with effort, or without effort, influences household consumption choices. In our experiment, we randomly assigned earning status along with decision-making status either to the husband or to the wife for every participating couple. So, the earning status as well as the decision-making status was given to the same (randomly) chosen partner. We took particular care to design the experiment in this way to ensure that the decision-maker’s choice in the experiment could not be influenced by any belief/ misunderstandings about his/ her partner’s consumption choice in the game. That is, the decision-maker in the experiment could not have chosen the personal consumption bundle with the hope/ belief that his/ her partner will choose the joint household consumption bundle, since only one of the partners had the opportunity to choose the bundles.

The earner/ decision-maker received money unconditionally without any effort, or conditionally on completing a real-effort task. The earner/ decision-maker was then presented with two consumption options and asked to use the money from the experiment to choose one of them. The participants could choose between (1) a bundle containing “assignable” (Browning et al. 1994, Lundberg Pollak and Wales 1997) private consumption goods (gender-specific clothing), or (2) a bundle containing joint household consumption goods (food items). See Figure 1 for the consumption bundles. Once the experiment was over, the decision-maker was given a store credit receipt (from designated stores) specifying their choices. The shopkeepers maintained picture records (for examples, see Figure 2)2.

Figure 1. Consumption bundles

Figure 2. Picture records kept by shopkeepers of purchase decisions

Findings

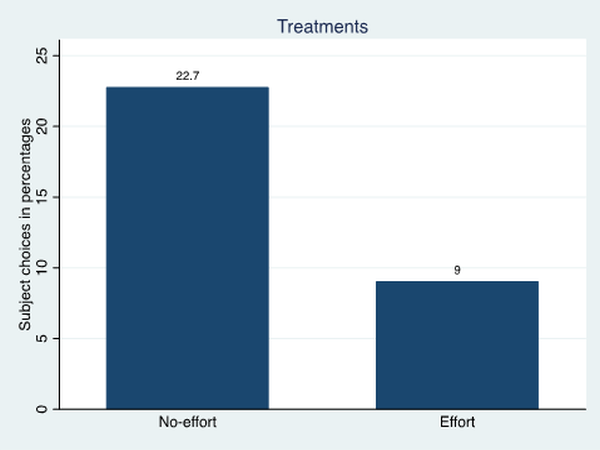

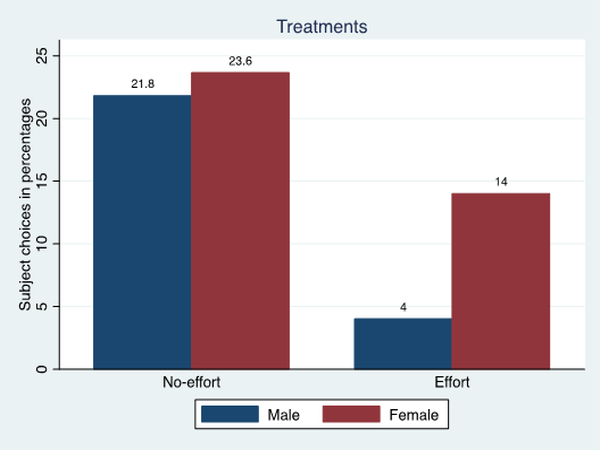

Figure 3 describes the percentage of subjects who choose the joint household consumption good for the ‘earning with effort’ and ‘earning without effort’ situations. We find that 22.7% of the subjects choose the joint consumption bundle in the no-effort treatment, and only 9% of the subjects choose the joint consumption bundle in the effort treatment. We further examine the distribution of these choices by gender in Figure 4. We find that 21.8% of the male subjects assigned to the no-effort treatment choose the joint consumption bundle. However, only 4% of the male subjects assigned to the effort treatment choose the joint consumption bundle. In contrast, 23.6% of the female participants chose the joint consumption bundle in the no-effort treatment, and 14% choose it in the effort treatment.

Figure 3. Choice of joint household good, by treatments

Figure 2. Picture records kept by shopkeepers of purchase decisions

Figure 4. Choice of joint household good, by treatments and gender

Our results from formal tests indicate that subjects in the effort treatment are significantly less likely to choose the joint consumption bundle compared to subjects in the no-effort treatment. Further, male participants are significantly less likely to choose the joint consumption bundle compared to females in the effort treatment. Male and female subject choices for joint consumption bundles are not significantly different in the no-effort treatment. Males are less likely to choose the joint consumption bundle in the effort treatment compared to the no-effort treatment. Finally, there is no statistically significant difference in the choice of joint consumption bundle for females across treatments (even though there seems to be a dip observationally). Accounting for socioeconomic characteristics such as age, completed grades of schooling, number of children, and household income result in similar findings that women are relatively more sensitive to joint household consumption independent of how they receive the income3.

Policy implications

Our results have implications for the classic conjectures on common preference models of the family. The classic conjectures suggest a form of Ricardian equivalence, that is, which family member receives or controls income should not affect the allocation of family resources, suggesting that gender-targeted transfer policies might be unnecessary.

In our experiment we independently vary the income earner as well as the conditions for earning, and find wives’ choices are relatively more altruistic, and cater more towards joint household consumption compared to husbands. This is especially stark when the wife earns the income and is also the decision-maker. Our conclusion is similar to that of Lundberg, Pollak and Wales (1997) who investigate consumption patterns using changes in a pilot policy in the late 1970s in UK as a natural experiment, where mothers started receiving child benefits instead of fathers.

Consequently, our results broadly support the conclusion of enhancing the role of women in the household. The steps taken by countries such as Mexico and Sri Lanka, where food coupons were directed towards women rather than men, and India’s recent step towards making women the head of the household for food distribution purposes, seem positive moves to improve household welfare keeping in mind the more altruistic concerns that wives exhibit.

Further, our results suggest that a push towards women’s empowerment (Duflo 2012), especially through greater participation of women in the labour force, can have positive benefits for joint household consumption and development, as empowered women seem to care significantly more for household consumption than empowered men.

Notes:

- http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/09/are-men-useless-government-says-yes/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0

- The husbands and the wives also participated in a household survey independently after the choice task.

- The full regression results are provided in Dasgupta and Mani (2013a).

Further Reading

- Browning, M., F. Bourguignon, P. Chiappori, and V. Lechene (1994), “Income and Outcomes: A Structural Model of Intrahousehold Allocation”, Journal of Political Economy, 102(6): 1067-96.

- Dasgupta, U. and S. Mani (2013a), Only Mine or All Ours: An Artefactual Field Experiment on Procedural Altruism´, Fordham, Discussion Paper No. 2013-01.

- Dasgupta, U. and S. Mani (2013b), “Altruism in the Household: A Pilot Study”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XLVIII (33).

- Datt, G., and Joliffe, D. (1999), ‘The Determinants of Poverty in Egypt’, IFPRI, Washington, D.C., mimeo.

- Datt, G., Simler, K., and Mukherjee, S. (1991), ‘The determinants of Poverty in Mozambique’, IFPRI, Washington, D.C. final report.

- Duflo, E. (2012), “Women Empowerment and Economic Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), pp.1051–1079.

- Kabeer, N. (1999), ‚The conditions and consequences of choice: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment‘, UNRISD, Discussion Paper No. 108,, Geneva.

- Lundberg, S., Pollak, R. A., & Wales, T.J. (1997), “Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom Child Benefit”, Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), pp 463-480.

- Quisumbing, A., and Maluccio, J. (2000), ‘Intrahousehold Allocation and Gender Relations: New Empirical Evidence from Four Developing Countries’, FCND Discussion Paper 84, IFPRI, Washington, D.C.

- Udry, C., Hoddinott, J. Alderman, H. and Haddad, L. (1995), “Gender Differentials in Farm Productivity: Implications for Household Efficiency and Agricultural Policy”, Food Policy, 20 (1995): 407-423.

- Vyawahare, M (2012), ‘Are Men Useless? (Government Says Yes)’, India Ink, The New York Times, 9 March 2012.

24 February, 2014

24 February, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.