In this post, Izvorski and Karakülah contend that comparisons between today’s developing countries and today’s advanced economies can provide aspiration but less so in terms of recommendations about policies and institutions. Of greater value for developing countries are comparisons with advanced economies when they were less prosperous. Using government spending a century ago by 14 of today’s advanced economies, they highlight four lessons for developing countries.

This blog was originally published by the Brookings Institution.

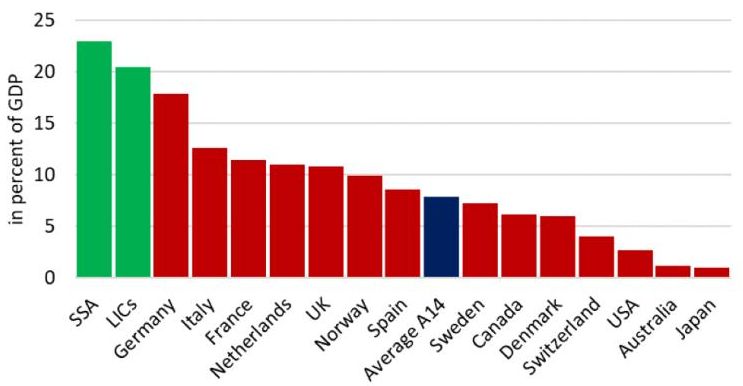

Many of today’s poorest countries do not collect adequate revenues to build the human capital, infrastructure, and institutions needed for stronger growth and faster poverty reduction. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 15 of the 45 countries have revenues lower than 15% of GDP (gross domestic product). Moreover, sub-Saharan Africa’s resource-rich countries have revenues that are more volatile and lower than countries that are resource-poor (Izvorski et al. 2018). Even with substantial foreign grants and loans, government spending by developing countries is lower than by advanced economies. In 2018, government spending in sub-Saharan Africa averaged 23% of GDP compared with 31.4% in middle-income countries and almost 39% in the advanced ones.

Comparisons between today’s developing countries and today’s advanced economies can provide aspiration but less so in terms of recommendations about policies and institutions. Of greater value for developing countries are comparisons with advanced economies when they were less prosperous and would have been considered low-income or lower middle-income. Using government spending a century ago by 14 of today’s advanced economies (Advanced 14), we highlight four lessons for developing countries. We develop these lessons in greater detail in a forthcoming working paper.

Lesson 1: Governments can advance development even with low levels of government spending.

Today’s low-income countries spend more than twice on average than today’s advanced economies spent more than a century ago (Figure 1). To be sure, this difference reflects the lack of the tax instruments and systems we have today. From 1850 until the early 1900s, customs duties and excises provided the bulk of government revenues, while the personal income tax and VAT (value-added tax) were not introduced in countries until later. Moreover, society’s expectations from the government were much different then. In 1900, for example, spending on unemployment, health, pensions, and housing amounted to only 1.1% of GDP in the Scandinavian countries on average and to 0.7 percent of GDP in the US (Lindert 1994). Even with low level of government spending, economic development was brisk in most of the Advanced 14 at the turn of the 20th century, with infrastructure improvements financed by private capital, and the strong expansion of primary and secondary education.

And here lies the lesson for today’s developing economies: While working on strengthening domestic taxation and raising more revenues to finance public goods, the priority needs to be on improving the business environment to attract private capital – mobilising private finance for development.

Figure 1. Governments of today’s low-income countries spent more on average in 2018 than today’s advanced economies did in 1900 (in % of GDP)

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s Prudence and Profligacy Database, IMF Fiscal Monitor 2018, World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), and authors’ estimates.

Notes: LIC = low-income countries; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; A14 = the average of the Advanced 14 in the figure. GDP per capita of the Advanced 14 in our sample averaged US$2,722 in today’s prices during the last decade of the 19th century; in 2016, per capita GDP in sub-Saharan Africa averaged US$2,757.

Lesson 2: Today’s developing economies need to focus on building fiscal and market institutions before rising spending needs – and not after they materialise.

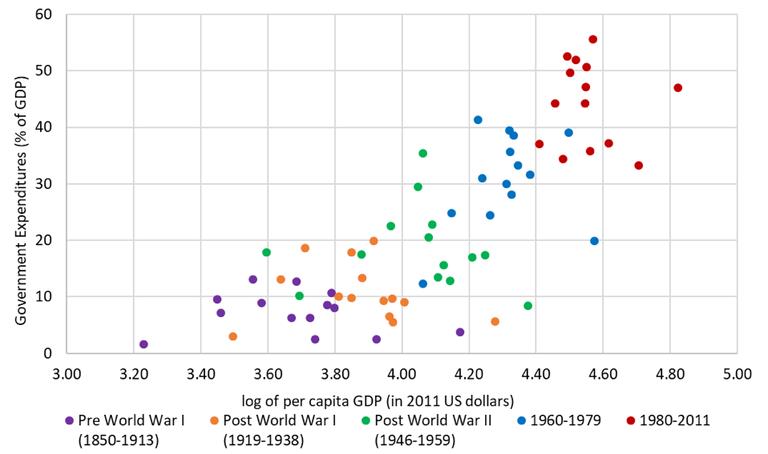

Government spending in the Advanced 14 increased substantially since 1960 as they re-evaluated the role of government amid rapid industrialisation and globalisation "and new taxes" became commonplace (Figure 2). The shift from agrarian to industrial to post-industrial economies required different worker skills. Economic disruptions reshaped governments in the past, as is happening now with the changing world of work, leading to a large expansion of social insurance and protection spending.

Figure 2. Government spending of the Advanced 14 rose significantly in the 20th century (in % of GDP)

Source: Authors’ calculation using the IMF’s Fiscal Prudence and Profligacy database and the Maddison Project Database 2018.

Note: The Figure plots only government spending of the Advanced 14.

Lesson 3: Government spending by today’s developing economies is likely to increase, but there is a choice to make to the extent of redistribution and government services.

Government spending among the advanced economies has increased, but so has its variability. Before 1913, spending among the advanced economies ranged from less than 2% of GDP in Japan to 13% in Italy, or a span of 11 percentage points. Today, the span of spending among the advanced economies is 39 percentage points: from 17.3% in Hong Kong to 56.4 in France.

Development paradigms vary among today’s advanced and developing countries. Robust growth can happen with a smaller or a larger government, in general. Too large of a redistribution, however, may create substantial disincentives to work and invest, or lead to tensions between formal and informal workers, employees of large companies or State-owned enterprises and small private firms. This danger now is clearer than ever: The changing world of work is clashing with persistent informality in developing countries and social protection systems that cover only part of the population.

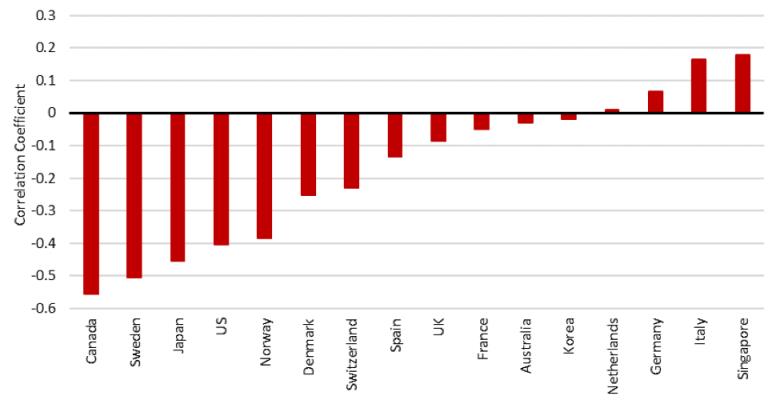

Lesson 4: Government spending has been countercyclical since World War II in almost all advanced economies, even with the sustained trend of spending increases (Figure 3).

Countercyclical fiscal policy is a must for today’s developing countries, especially for those with abundant natural resources. However, there is overwhelming evidence that fiscal policy has been consistently pro-cyclical in developing countries (World Bank, 2017), resulting in profound macroeconomic imbalances, unproductive debt build-ups, and ongoing instability.

Figure 3. Government spending has been countercyclical in today’s advanced economies, 1950-2011 (in % of GDP)

Source: Authors’ calculation using the IMF’s Fiscal Prudence and Profligacy database, World Bank’s WDI, and the Maddison Project Database 2018.

Note: The Figure plots the correlation between the cyclical component of real GDP and the cyclical component of real government spending.

Further Reading

- Izvorski, Ivailo, Souleymane Coulibaly and Djeneba Doumbia (2018), ‘Reinvigorating Growth in Resource-Rich Sub-Saharan Africa’, The World Bank Group.

- Lindert, Peter H (1994), “The Rise of Social Spending, 1880-1930”, Explorations in Economic History, 31(1): 1-37.

- The World Bank (2017), ‘Leaning against the wind: Fiscal policy in Latin America and the Caribbean in a historical perspective’, April 2017.

14 June, 2019

14 June, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.