The male breadwinner norm – the idea that a man must earn more than his wife – can potentially impact labour-market outcomes of married women. Using nationally representative data from India for the period 1983-2012, this article shows that if the wife’s share of income in the family exceeds that of her husband’s, she is less likely to work and more likely to earn less than her potential if she does work.

#InternationalWomensDay #IWD2021 #GenerationEquality

Low levels of female labour force participation (FLFP) in India, amidst improvements in women’s educational attainment and declining fertility rates, has been a big puzzle and hence the focus of recent literature. Even when women work, they tend to earn less than their male counterparts, on average. Recent research highlights the role played by identity and cultural norms in affecting an economic agent’s behaviour in the labour market (Alesina et al. 2013, Fortin 2005, Bertrand et al. 2015). Recent studies seeking to explain low FLFP in India have followed suit, and explore social and cultural norms in addition to traditional factors such as education, urbanisation, and ‘availability of suitable jobs’ (Afridi et al. 2019, Bernhardt 2018, Field et al. 2016).

Male breadwinner norm and FLFP in India

Norms refer to a society’s informal rules about what is considered as appropriate or acceptable behaviour. In this article, I study one such norm, namely the ‘male breadwinner norm’ which is the idea that a man should earn more than his wife (Gupta 2021). This norm is prevalent – in varying degrees – across both developing and developed countries. Both survey and anecdotal data support the acceptance of this norm in society. The World Value Survey (1995), revealed that more than half (54%) of the respondents in India strongly agreed/agreed with the statement: “If a woman earns more money than her husband, it’s almost certain to cause problems”. This figure is much than that of China (33%), US (40%), and Sweden (32%). Not only do such norms seem to be more dominant in developing countries such as India, they coexist with other strong cultural norms (like patrilocality/patrilineality1 and ideas of purity associated with women that do not work). Additionally, in India, as per data from the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS)-II (2011-12), a majority of women report having relatively less control over their labour force participation decisions. These forces combine to imply that identity and norms may play a more important role in determining labour market outcomes for women in India.

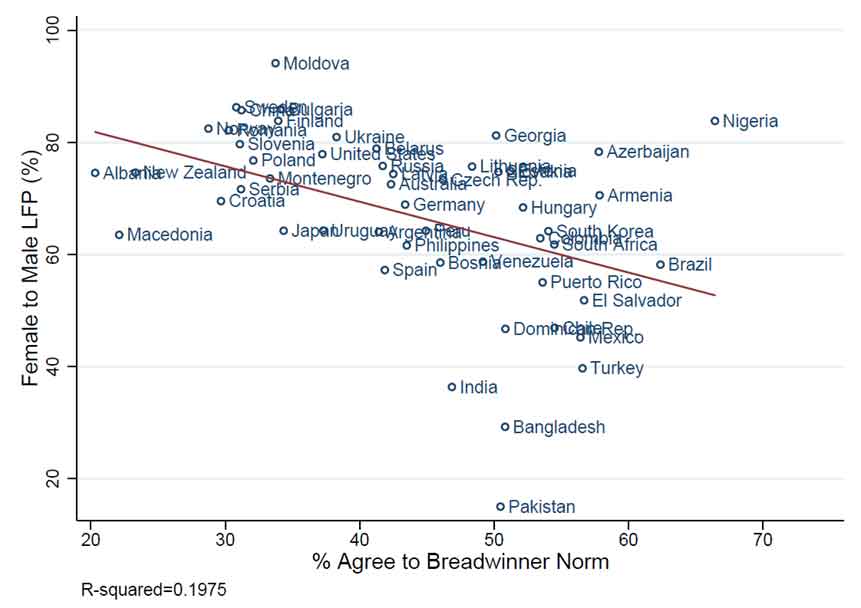

One way that compliance to the male breadwinner norm can occur is through the alteration of labour supply decisions at the ‘intensive margin’ (for example, by choosing the wage rates or hours of work in order to ensure that she earns less than her husband) by women. However, couples may also respond to this norm by making ‘extensive margin’ choices wherein women drop out of the labour force altogether. The extensive margin response that women would drop out of the labour force altogether to adhere to the male breadwinner norm may seem far-fetched and may not be immediately obvious. However, Bertrand et al. (2015) show that such responses exist in the US. Further, Figure 1 shows that across countries, there is a strong negative relationship between acceptance of breadwinner norms and female-to-male labour force participation (LFP) ratio. This suggests that the effects on the extensive margin could be substantial. Accompanied with the fact that like most norms, the male breadwinner norm may also be relatively slow to change, the persistent effect of this norm on labour market outcomes could have high economic costs for a country, especially for women.

Figure 1. Male breadwinner norm and female-to-male LFP ratio

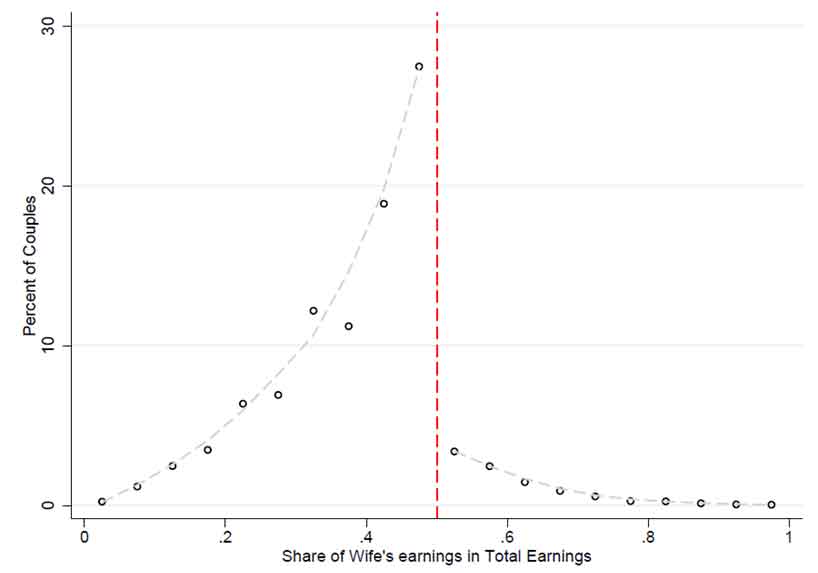

Relative incomes of married couples

Using 10 rounds of the Employment and Unemployment modules of National Sample Survey (NSS) data from 1983-2012, I begin by establishing the fact that similar to the western experience (Bertrand et al. 2015, Wieber and Holst 2015, Sprengholz et al. 2019, Roth and Slotwinski 2020, Zinovyeva and Tverdostup 2018), among married couples in India, the distribution of the share of household income that is earned by the wife witnesses a sharp drop at 0.5 (50%) (where the wife starts to earn more than the husband). Similar discontinuity is observed when I use IHDS-I (2004-05) data instead.

Figure 2. Distribution of relative income of married couples

In their seminal research, Bertrand et al. (2015) examine this discontinuity in the context of the US and discuss how standard models of the marriage market fail to adequately explain this peculiarity and attribute this observation to the male breadwinner norm. I attempt to extend their analysis to a context where norms might matter more. Consistent with the evidence from the World Value Survey, that the male breadwinner norm seems to be more prevalent in India than in the US, I observe a much larger discontinuity to the right of 50% share of income earned by the wife in case of India (Figure 2) compared to the Bertrand et al. (2015) calculations for the US.

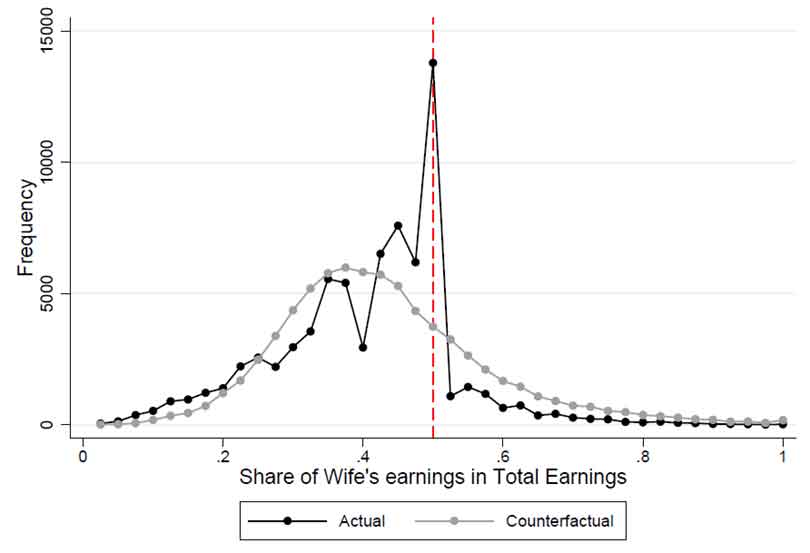

Moreover, to test if the norm is binding, that is, to test if couples are altering their behaviour due to this norm, I construct a counterfactual distribution (Figure 3) for relative income within households by replacing the actual income of the wife with the average income of women in her demographic group (based on age, education, caste, rural/urban, state, and time). If couples are altering their behaviour in response to this norm, we would expect the counterfactual distribution to have greater (smaller) mass to the right (left) of 50% share of wife’s income than the actual distribution. This is what we observe in Figure 3, which suggests that some couples might have moved from greater than 50% share of wife’s income to at or just to the left of 50% share in response to the norm. Hence the norm seems binding.

Figure 3. Actual and counterfactual distributions of the share of wife’s earnings

More recent literature (Zinovyeva and Tverdostup 2018, Roth and Slotwinski 2020, Binder and Lam 2018) questions the interpretation of this sharp drop as consequence of the breadwinner norm and presents alternative hypotheses like misreporting, institutional factors, etc. Though completely plausible explanations, using testable implications from this literature, I provide some suggestive evidence that we cannot completely rule out the role played by the breadwinner norm in case of India.2,3

Married women’s labour supply decisions: The intensive and extensive margin

Next, I try to understand if and how the male breadwinner norm affects female labour supply at both the intensive and extensive margins in India. Specifically, I test if the breadwinner norm leads the wife to lower her LFP (effect on the extensive margin) or adjust labour supply in a way that she earns less than the husband (effect of the intensive margin). Using repeated cross-sectional data4 (NSS5) on Indian married couples engaged in wage and salaried jobs, I show that a 10 percentage point increase in the probability that the wife earns more than the husband, reduces her likelihood of LFP in wage and salaried jobs by roughly 1-1.7 percentage points. For a woman who is engaged in a wage or salaried job, the same change also increases the gap between her actual earnings and her potential earnings by about 2-3 percentage points. Given the recent debate (Kabeer, Deshpande and Assaad 2019) around the definition of FLFP in India, I also look at the effect on broader definitions of LFP (which include own account work as well as extra domestic duties) and find smaller but significant results. Both these results are statistically and economically significant and sizeable when compared to developed nations like the US.

Furthermore, looking at relative incomes of married couples in IHDS-I, and LFP in IHDS-II, I find that a woman who was earning more than her husband in 2005 is more likely to leave the labour market by 2012. This exit from the labour market of women earning more than their husbands is entirely driven by couples where the wife stated that her husband had more of a say in her labour market decisions. Although suggestive, this further provides evidence that identity and gender norms like the male breadwinner norm are crucial drivers of labour market outcomes for women in India.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Patrilocality refers to a system wherein a married couple resides with or near the husband's parents. Patrilineality is a system in which an individual's family membership is derived and recorded through their father's lineage.

- For couples working in the same industry and occupation, one can expect that the spike at 50% share of income is institutional as they get paid the same wages. I find that even for couples who work in different industries and occupations the discontinuity (although smaller) exists.

- To explore the role of misreporting, I compare the difference in household consumption and total reported income of couples at and around the 50% share of wife’s income. Misreporting is less of a concern if the expected value of this difference is smooth around the cut-off of 50%.

- Repeated cross-sectional data collect information on different sets of individuals at various points in time; thus, how the status of a particular individual or group changes over time cannot be observed.

- For the repeated cross section, I used 10 rounds of NSS (Rounds 38, 43, 50, 55,60, 61, 62, 64, 66, 68) covering the period 1983-2012.

Further Reading

- Afridi, F, M Bishnu and K Mahajan (2019), 'What Determines Women's Labor Supply? The Role of Home Productivity and Social Norms', IZA Discussion Paper No. 12666.

- Afridi, Farzana, Taryn Dinkelman and Kanika Mahajan (2018), "Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades" Journal of Population Economics, 31: 783-818.

- Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano and Nathan Nunn (2013), "On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2): 469-530.

- Bernhardt, Arielle, Erica Field, Rohini Pande and Natalia Rigolia and Simone Schaner and Charity Troyer-Moore (2018), "Male Social Status and Women's Work", AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 363-67.

- Bertrand, Marianne, Emir Kamenica and Jessica Pan (2015), "Gender identity and relative income within households", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2): 571-614.

- Binder, Ariel J and David Lam (2018), 'Is there a male breadwinner norm? The hazards of inferring preferences from marriage market outcomes', NBER Working Paper No 24907.

- Field, E, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner and C Troyer-Moore (2016), 'On Her Account: Can Strengthening Women’s Financial Control Boost Female Labor Supply?', Working paper.

- Fortin, Nicole M (2005), "Gender role attitudes and the labour-market outcomes of women across OECD countries", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3): 416-483.

- Gupta, S (2020), 'Labor Market Response to Gendered Breadwinner Norms: Evidence from India', Working paper.

- Jayachandran, S (2020), 'Social norms as a barrier to women's employment in developing countries', NBER Working Paper No. 27449.

- Kabeer, Naila, Ashwini Deshpande and Ragui Assaad (2019), 'Women's access to market opportunities in South Asia and the Middle East & North Africa: barriers, opportunities and policy challenges', London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of International Development

- Roth, A and M Slotwinski (2020), 'Gender norms and income misreporting within households', ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No 20-001.

- Sprengholz, M, A Wieber and E Holst (2019), 'Gender identity and wives' labor market outcomes in West and East Germany between 1984 and 2016', IZA Discussion Paper No. 12284.

- Wieber, A and E Holst (2015), 'Gender identity and womens' supply of labor and non-market work: Panel data evidence for Germany', IZA Discussion Paper No. 9471.

- Zinovyeva, N and M Tverdostup (2018), 'Gender identity, co-working spouses and relative income within households', IZA Discussion Paper No. 11757.

08 March, 2021

08 March, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.