To explain the gap between the expectation of perfect outcomes and the reality of an imperfect system, Gaurav Goel puts forth The Governance Matrix, a tool which can be used to assess the readiness of a government to successfully implement initiatives. He explains the two axes – political salience and system capacity – along which political systems can move; based on this, he posits four states in which governments can exist, and examines the potential for sustainable change in each of the quadrants.

The Indian government system is something of an enigma. Nurtured to cater to a resolute yet fraught democracy, with roots in an oppressive colonial past, it is a system that has to work for a population more diverse and bigger than any other modern democracy. To say that governing India – with more than 1.3 billion people, across 28 states and 8 Union Territories – is complicated, is an understatement.

Collectively, the national, state, and local governments have the responsibility of ensuring a stable economy, providing critical services (like education, health, nutrition) and enabling inclusive growth. To carry out these responsibilities, governments work through different programmes, schemes, and missions – in the interest of simplicity, let’s collectively refer to these as ‘initiatives’. While some government initiatives prove to be successful, in that they come close to achieving the outcome for which they were designed, many don’t meet the mark. For example, Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen (SBM(G)) was launched in 2014 as a national campaign to eliminate “open defecation in rural areas during the period 2014 to 2019”. During that five-year period, SBM(G)’s target was largely achieved, with rural India being declared open-defecation free. On the other hand, the Skill India Mission, launched in 2015, aimed to provide market-relevant skills training to 400 million youth by 2022. As of December 2021, only around 134 million youth across the country had been trained under the scheme. Both of these are union government initiatives, which rely heavily on state and local governments for successful implementation.

While the success and failure of individual government initiatives have been studied in depth, what’s missing is an analysis of the underlying factors that determine these results. Analysing those factors can help any individual, non-governmental organisation, or the government itself to ascertain the system’s readiness for undertaking an initiative and its ability to achieve the intended outcomes.

What is The Governance Matrix?

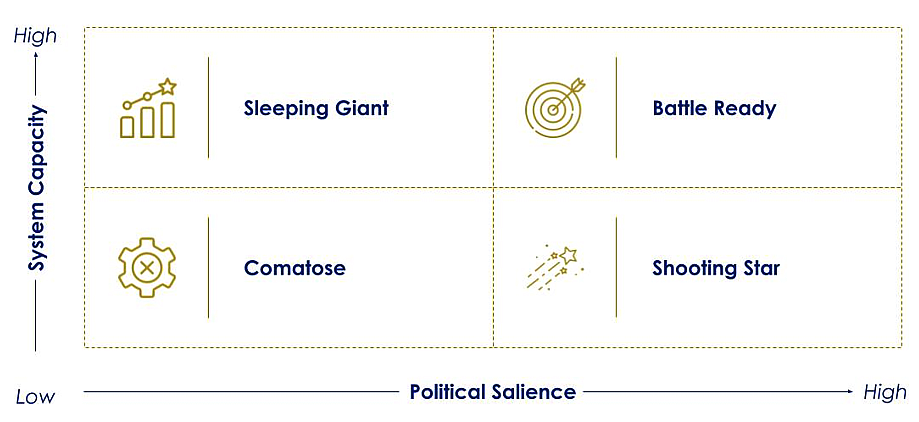

The Governance Matrix1 is a tool that can be used to ascertain the readiness of a government system (national, state or local) to drive outcomes as a function of the level of political salience (political will on a given agenda) and system capacity (people, processes and infrastructure). In Figure 1, the system can move from one quadrant to another through a change in either political salience (through advocacy or a change in political environment) or in system capacity (through investment in people, processes, and infrastructure).

Figure 1. The Governance Matrix

Understanding The Governance Matrix

The Governance Matrix has two axes: the first, political salience, refers to the commitment of the political leadership of the government system to introduce and carry out an initiative for a prolonged period of time until the intended outcome is achieved. If there is political will, then enabling conditions will be put in place by the leadership to increase the probability of achieving outcomes. This includes posting an appropriate bureaucrat at the helm of affairs with some stability of tenure – and even if transfers happen over a period to replace the original bureaucrat with another competent officer; ensuring the availability of resources needed for the initiative, particularly in the form of budgets and team; and rallying public support for the initiative through speeches, events, media, advertisements and so on.

The second axis of The Governance Matrix is system capacity, which refers to the people, processes and infrastructure (both physical and technology) required to drive an initiative successfully. For example, health outcomes can’t be achieved when the vacancies of doctors continue to remain high in primary health centres (people). Educational outcomes can’t be achieved if teacher availability in classroom is not ensured, which in turn depends on the administrative workload on teachers (process). The country’s youth can’t be skilled effectively if there isn’t a network of well-equipped training centres (physical infrastructure). And it would be next to impossible to carry out direct benefit transfers successfully to farmers in the absence of suitable payment systems and an updated database of all eligible beneficiaries with verified bank accounts (technology infrastructure).

The four quadrants of The Governance Matrix explain the four states in which a government system can be, as defined against the axes of political salience and system capacity:

- In a ‘Comatose’ system, both political salience and system capacity are low. In this situation, the system’s entire energy is spent on maintaining the status quo. There is neither the inclination nor the capacity to drive initiatives. A change in political salience and/or system capacity would be needed to nudge the system into action.

For example, women’s safety is a critical reform area, the importance of which cannot be overstated. However, despite the urgent need for reforms, this is an issue that has historically never gained enough political salience. Across states, system capacity to prevent crime against women has also remained low. In the aftermath of the Nirbhaya case in 2012, it seemed like the issue would receive higher political salience. An effort was also made to strengthen system capacity, with the Ministry of Women and Child Development and Ministry of Finance setting up the Nirbhaya Fund “for projects specifically designed to improve the safety and security of women”. However, political salience on the issue fell through soon enough, and system capacity continues to be low, even as the Nirbhaya Fund remains persistently underutilised. With low political salience and low system capacity, states are unlikely to make tangible improvements on women’s safety. - In a ‘Sleeping Giant’ system, political salience is low and system capacity is high. In such a situation, while ongoing incremental outcomes can be achieved, complex sustainable outcomes that make a fundamental lasting difference to the quality of life of citizens can only be achieved by building political salience around the goal. This can happen either through advocacy, a change in political leadership, or through ground-up citizen movements which demand reforms. In essence, the real potential of the system can be unlocked through political salience around an agenda.

The Indian Railways is a good example of a Sleeping Giant. While there have been no political pledges for ground-breaking changes with regards to railways over the years (low political salience), the overall capacity of the system is relatively high with tight processes (like effective booking and grievance redressal mechanisms), a strong cadre of officers and good infrastructure. The Railways Ministry has been fairly consistent in introducing incremental changes on an ongoing basis, but both the pace and scale of transformation remain limited. There are no significant breakthroughs with respect to improving finances, ushering in technology and overhauling citizen experience. More ambitious transformation within railways is possible only if higher political salience can be built around making it a state-of-the-art transportation system for the country. - In a ‘Shooting Star’ system, political salience is high, but system capacity is low. In such a situation, targetted short-term outcomes can be achieved. However, this is also not ideal because deeper systemic reforms cannot be carried out with low system capacity. The system’s weakness cannot be repaired by stronger political will alone. Therefore, the focus in this situation has to be on strengthening system capacity by augmenting the workforce, fixing processes, and bolstering infrastructure so as to increase the breadth, depth and sustainability of outcomes.

One example of a Shooting Star is the Indian health system. Across the country, at various administrative levels, the health system leaves much to be desired owing to low capacity. However, when Covid vaccination had to be delivered on war footing across the country, the same system was able to deliver outcomes, and India fully vaccinated 89% of its adult population when it was in mission-mode. This was an example of a targetted short-term outcome being achieved on the back of high political salience. However, this by no means is an indicator of the robustness of the country’s health system, which continues to be plagued by a shortage of doctors, limited or absent processes to check the quality of treatment received by patients, and broken infrastructure, especially in rural areas. So, if a new pandemic strikes the country, the health system continues to run the risk of a collapse in the absence of deep reforms which can improve system capacity. - In a ‘Battle Ready’ system, both political salience and system capacity are high. In this situation, the system can achieve complex sustainable outcomes. Such outcomes can make a fundamental lasting difference to the quality of life of citizens. Initiatives launched when the system is in the Battle Ready quadrant stand the highest chance of succeeding.

The Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY) is an example of an initiative carried out when the banking system was Battle Ready. The scheme was designed to provide “universal access to banking facilities with at least one basic banking account for every household, financial literacy, access to credit, insurance and pension facility”. Between 28 August 2014, when JDY was launched, and 30 June 2015 – a mere 10-month period – 165 million bank accounts had been opened. The Jan Dhan Yojana had high political salience, with the Prime Minister declaring it a national priority. Over the years, a strong push towards opening branches in rural and poorly-served areas, coupled with mandates like priority sector lending, ensured that public sector banks had already established deep and strong networks beyond tier-2 and tier-3 cities, with people, processes and infrastructure in place. Therefore, when this high-capacity system was propelled into action with high political salience, it was possible to carry out a transformative initiative.

Conclusion

The Governance Matrix does not posit that these four quadrants are the final state for any system. It in fact brings to light the levers – political salience and system capacity – which can be used to move a system from one quadrant to another. It also showcases how critical both of these levers are for achieving developmental outcomes. When both political salience and system capacity are low, no change is possible, and the status quo is maintained. High system capacity with low political salience means the scale and pace of change remain limited. High political salience without system capacity limits the breadth, depth, and sustainability of outcomes. When both are high, the probability of achieving intended outcomes is highest.

Quite often, well-meaning practitioners and researchers engaging with or in government expect an imperfect system to yield the perfect outcomes, purely based on intent and inputs. The Governance Matrix can help explain the gap between this expectation and reality.

Note:

- The Governance Matrix is based on learnings accumulated by Samagra, a mission-driven governance consulting firm, from a decade of experience working with governments at the centre, states, and districts on varied domains such as education, health, employment, skilling, and agriculture. It can be used to ascertain a national, state, or local government system’s readiness to achieve outcomes related to any government initiative.

02 December, 2022

02 December, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.