Women in India spend thrice as much time doing unpaid domestic work compared to the men in their household, and twice as much time on care-giving activities for children and dependent adults. Based on a 2019 survey in four urban clusters in north India, this article examines the relationship between the expectations placed on women by the marital household they live in, and the potential for them to work outside it.

This is the fourth in a five-part series on ‘Urbanisation, gender, and social change’.

In 2019, the National Statistical Office (NSO) of India conducted a time-use survey revealing that women spend thrice as much time doing unpaid domestic work compared to the men in their household. The survey also revealed that women spend twice as much time on care-giving activities for children or dependent adults in the home. In many countries around the world, domestic obligations hold influence over women’s decisions in a way that they do not for men. Drawing on unique survey evidence from Pakistan, Khan (2021) finds that women, unlike men, prioritise the requirements of the household while rating their policy preferences, and consider their own needs – as autonomous individuals – as subordinate issues.

How do the demands of homemaking, particularly care work, restrict women from seeking employment?

Home versus work

Marriage is often cited as the foremost reason women either leave the workforce or do not enter it at all, given the increased expectations of women’s work within the household (Bhandare 2018). To interrogate the relationship between the expectations placed on women by the marital household they live in and the potential for them to work outside it, in a recent study, we examine perceptions married couples hold about women’s employment (Karia and Mehta 2021). Our analysis relies on a unique survey conducted in 2019 across 7,829 households in four urban clusters in north India – Dhanbad (Jharkhand), Indore (Madhya Pradesh), Patna (Bihar), and Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh). Our data suggest that, for many women, the decision to work is made after marriage. As a result, the expectations of a marital home would regulate the relationship between women and their various work-life arrangements – potentially enabling, instead of uniformly constraining, their employment.

Hierarchies within a marriage

To assess the environment of the marital household, we consider the terms upon which a marriage is agreed to. Arranged marriages in India place the family – particularly the parents of the bride and groom – at the centre of pre-nuptial negotiations. The proportion of marriages decided entirely by partners remains low and even in these ‘love marriages’, the family’s approval remains paramount (Mukhopadhyay 2012). This is significant because these terms heavily influence the qualities sought after in women and men as partners.

In addition to predictable gendered notions of beauty and success, matrimonial advertisements also illustrate more substantive preferences for martial partners (Reyes-Hockings 1966). Primary importance is given to education and age of a potential partner. High educational qualifications are desirable in both women and men; however, evidence suggests that women remain keen to marry men who are more educated than them (Rao and Rao 1990). Similarly, it is extremely rare for men to seek women who are older than them. Further, we observe that it is common practice, especially in north India, for women to move into their husband’s house after marriage, often requiring them to migrate out of their hometown (Chakrabarti and Chaudhuri 2018).

These characteristics of ‘marriageability’, structure hierarchies between spouses that tend to favour the men. In our sample, we find that women are older than their husbands in only 1% of surveyed couples, and more educated in only 10%. Couples whose marriage can be classified as ‘exogamous’ (where the woman has migrated to her current place of residence for the marriage) make up 47% of the sample. Our study looks at how these hierarchies along with decision-making authority in various spaces within the home, influence people’s perceptions about women’s work. Where do norms that disfavour working women come from?

The burden of childcare

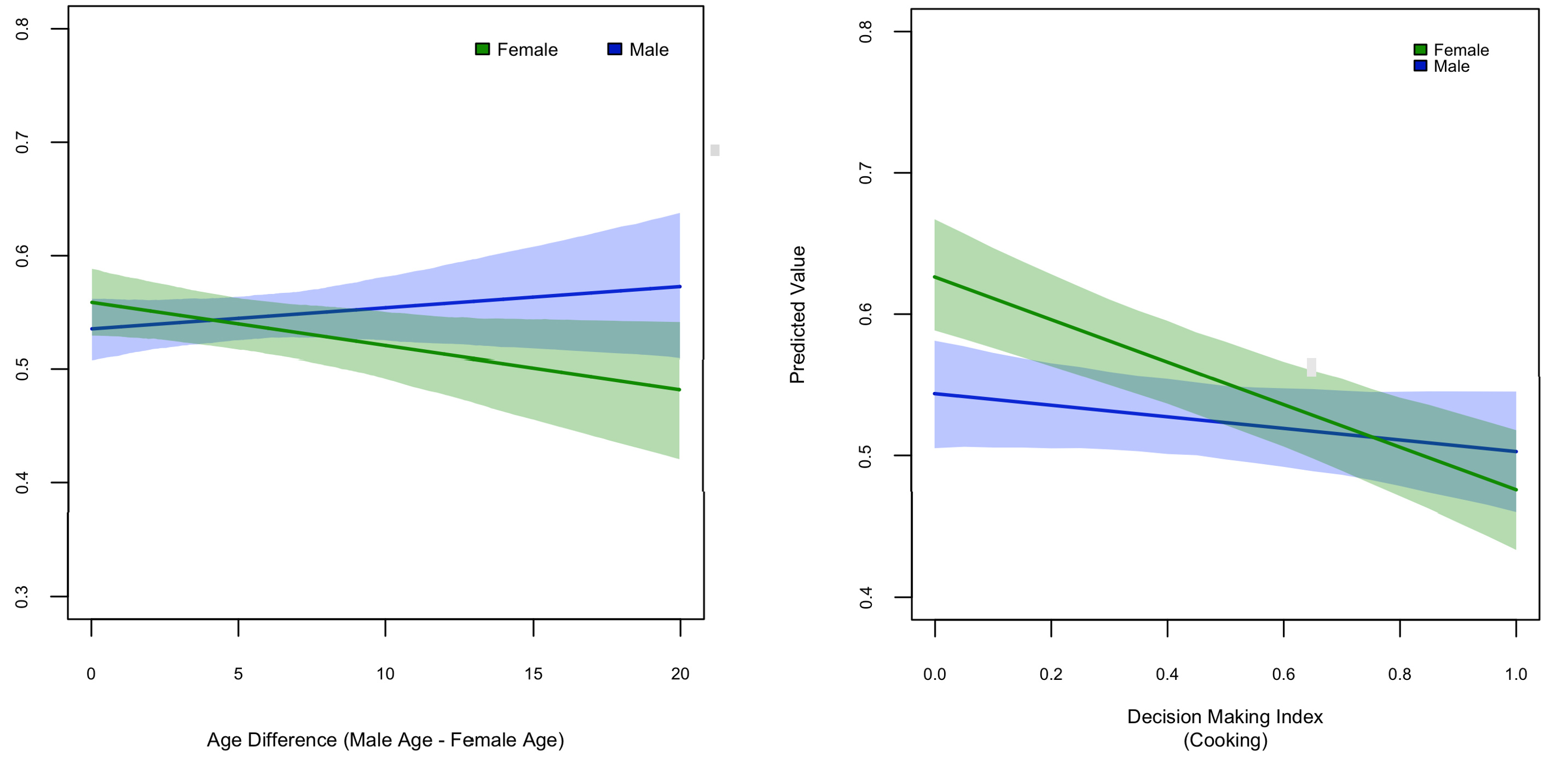

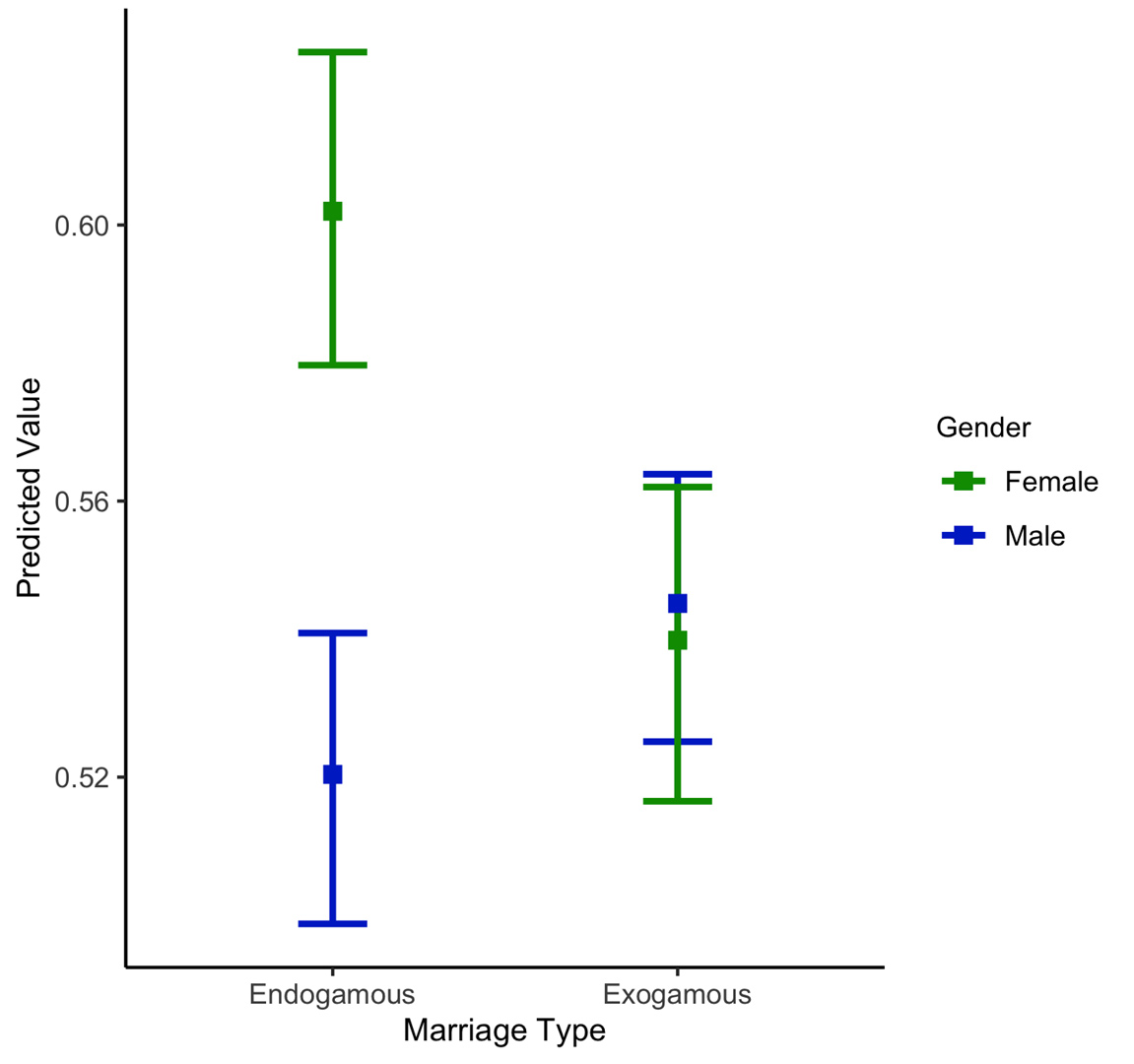

Throughout our analysis, motherhood emerges as a singular space of constraint for women in hierarchical marriages. The onus of being a ‘good wife’ and/or a ‘good mother’ translates into a norm that keeps women inside the home, rendering ‘work’ largely as the province of men. Women who are significantly younger than their husbands, are more likely to feel that children suffer when they have working mothers, as visible in Figure 1 (left panel). This is particularly noteworthy, since younger women married to older men hold an optimistic outlook on women’s work in other survey questions, but lose this view when it comes to motherhood. Their husbands, on the other hand, are positive about this question. Additionally, women who are the primary decision-makers in the kitchen, as well as those in exogamous marriages, also feel that working mothers create unfavourable environments for children (Figure 1 (right panel), and Figure 2).

Figure 1. Predicted perceptions of working mothers, by age difference (left panel) and household agency (right panel)

Notes: (i) These graphs display the predicted variance in men and women’s perceptions of working mothers with respect to: (a) The age difference between them, calculated by subtracting the woman’s age from the man’s age; and (b) The cooking-related decision-making index, where 1 indicates complete responsibility taken by the woman in the household, and 0 indicates that this authority lies with the man. (ii) While measuring perceptions, 1 denotes a completely favourable opinion of working mothers’ influence on their children, while 0 implies an unfavourable opinion.

Figure 2. Effects of exogamy on perceptions of working mothers

Note: This graph displays the predicted effects of marriage type on men and women’s perceptions about working mothers. Marriage type here is classified into a binary (taking either 0 or 1 as values) of exogamous and endogamous, indicating whether women have migrated to their current place of residence for the marriage.

Schooling decisions as a predictor

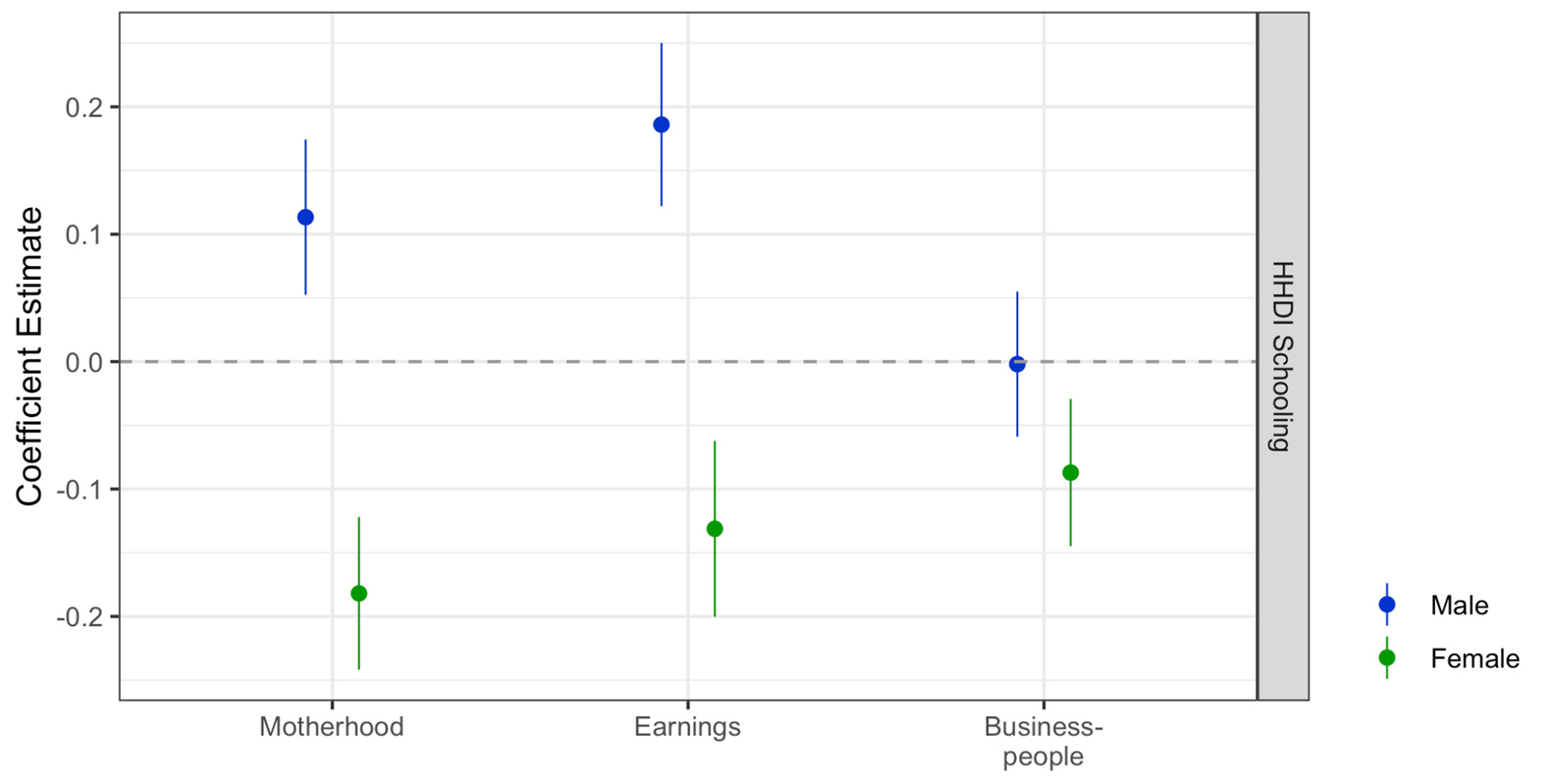

Bearing responsibility for schooling-related decisions makes women wary about investing in work outside the house on multiple fronts. In addition to the fact that they are strongly not in favour of working mothers, their responses suggest an internalisation of gendered roles that spills into other responsibilities. Women feel that earning more than their husbands will lead to problems in the house, and that they are not suited to be businesspeople in the way that men are. Here their husbands are far more positive than them in their responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effects of schooling-related responsibilities on women’s work

Notes: (i) This plot shows the effects of our schooling-related decision-making index on perceptions men and women hold about women’s work. (ii) Here, the dot indicates the marginal effects of women in the household taking complete responsibility for schooling-related decisions on the perceptions of both partners across three questions.

This disjuncture reflects a conservatism on behalf of these women that is likely born out of an imbalance in parental responsibilities. Having spent more time shouldering the responsibility of childcare, women are more realistic about the time and energy it requires. A recent study finds that urban Indian women who have young children – who require more time from their mothers – are much less likely to be employed than those who have older children, or other women in the home to share the burden with (Das and Zumbyte 2017). This forms the basis of biases held by employers as well – women tend to suffer wage and hiring disadvantages when re-entering the workforce after having children. Moreover, the ‘male-breadwinner norm’ in India is shown to directly influence women’s employment decisions (Gupta 2021). Women who earn more than their husbands are more likely to leave the labour market than women who do not.

Concluding thoughts

It is clear that from extant data that women in India engage in a significant amount of unpaid work within the home. There is an urgent need for standard definitions of work to recognise both formal and unpaid work in order to understand how public policies can support both partners to effectively share the burden of running a home. Doing so would reduce impediments women face in finding employment while raising children, and also acknowledge their contributions to the household as integral economic activities.

The next and final part in the series discusses the media’s role in shaping women’s political preferences.

I4I is on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Further Reading

- Bhandare, N (2018), ‘As Indian Women Leave Jobs, Single Women Keep working’, Indiaspend, 23 June.

- Chakrabarti, Anindita and Kausik Chaudhuri (2018), “Does employment before marriage exert autonomy after marriage? Evidence on female autonomy from India”, Oxford Development Studies, 46(2): 199-214. Available here.

- Das, MB and I Žumbytė (2017), ‘The Motherhood Penalty and Female Employment in Urban India’, Policy Research Working Paper 8004.

- Gupta, S (2021), ‘Gendered breadwinner norms and work decisions’, Ideas for India, 8 March.

- Karia, Shubhangi and Tanvi Mehta (2021), “Working Through Marriage: Effects of Marital Inequalities on Perceptions of Women’s Employment”, Urbanisation.

- Khan, S (2020), ‘Count Me Out: Women’s Unexpressed Preferences in Pakistan’, Working Paper.

- Mukhopadhyay, Madhurima (2012), “Matchmakers and Intermediation: Marriage in Contemporary Kolkata”, Economic and Political Weekly, 47(43): 90-99. Available here.

- National Statistical Office (2020), ‘Time Use in India-2019’, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation Report.

- Rao, Nandini V and VV Prakasa Rao (1990), “Desired qualities in a future mate in India”, International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 20(2): 181-198.

- Reyes-Hockings, Amelia (1966), “The Newspaper as Surrogate Marriage Broker in India”, Sociological Bulletin, 15(1): 25-39.

09 December, 2021

09 December, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.