Workfare programmes are an old tool to provide necessary income support to the poorest in times of recessions, droughts, and now pandemics. Yet, these are often questioned for their effectiveness. As ever more workers have been rushing to public worksites across rural India in mid-2020, this article on the early days of MNREGA during 2006-2008 suggests that it has the potential to considerably reduce seasonal income fluctuations and improve the livelihoods of many – when properly implemented.

The nationwide employment guarantee of 100 days of work under MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act)1 has been in place for almost 15 years. During this time, it has been studied widely by researchers, contested by different stakeholders, and on several occasions, it was on the brink of being discontinued altogether. Come 2020, MNREGA was at its peak, employing more people than ever with growing demands to extend the work guarantee to 200 days and to open “a million worksites” (Drèze 2020). As the welfare benefits of the world’s largest employment programme are being questioned once again, our research on the initial years of MNREGA provides some insights. We combine an original district-level dataset that elucidates the rollout of MNREGA between 2006 and 2008 with three National Sample Surveys conducted in 2007-08, to quantify income and consumption gains due to MNREGA. We also consider other welfare-related outcomes covered by those surveys, such as school attendance and child labour (Klonner and Oldiges 2019).

Employment programmes in India and elsewhere

In recent years, MNREGA has been employing around 50 million households annually, and around 55 million between April and July 2020 alone. The Centre’s total MNREGA expenditure outlays in the financial year 2019-20 were Rs. 679.5087 billion, around 0.3% of India’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product), which is still less than, for example, Ethiopia’s workfare programme that consumed 2% of the country’s GDP in 2007 (Lal et al. 2010).2

Public works programmes have not only been popular in India, where prior to MNREGA the employment programme in the state of Maharashtra of the 1980 and 1990s has been much studied too. In more recent years, in sub-Saharan Africa alone, some 150 public works programmes were active around 2010 (World Bank, 2013), while several large-scale public works programmes existed in Asia and Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s (Subbarao 2003). One reason for its popularity across continents is that workfare has the potential to ensure proper targeting (Besley and Coate 1992) and households can decide flexibly whether to supply their labour and receive benefits. In addition, public works programmes have the potential to build growth-enhancing local public goods (Gehrke and Hartwig 2018) as well as productive, useful private assets (Ranaware et al. 2015).

Previous research on MNREGA’s employment and poverty effects

Among academic economists interested in evaluating the Act’s performance, MNREGA has attracted a great deal of attention, too. To name just a few, nationwide studies on the early years by Imbert and Papp (2015) and Zimmermann (2020) find considerable labour market effects such as a rise in rural wages in districts where MNREGA was in place, and in both the agricultural off- and on-seasons. With regards to the Act’s effect on consumption expenditure and poverty, Deininger and Liu (2019) and Ravi and Engler (2015), for example, use more localised panel data from villages in Andhra Pradesh and find moderate welfare-improving effects caused by MNREGA.

Disentangling the effect of MNREGA

We develop a research design for national-level data to single out the programme’s poverty effects, which were previously most convincingly tested only on a smaller scale. Like earlier studies, our research design exploits MNREGA’s staggered roll-out between 2006 and 2008.3

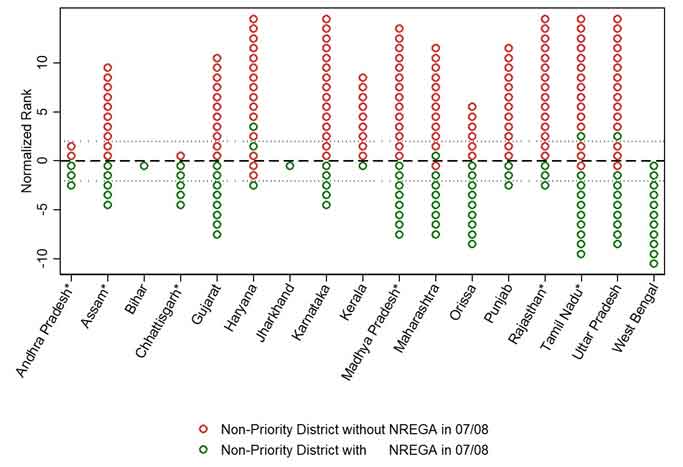

Our innovation is that we identify a subset of early MNREGA districts – ‘priority districts’ – that appear on three development priority lists of the Government of India for reasons of Maoist conflict, low human development, and severe agrarian distress. When these ‘priority districts’ are left aside, coverage by the MNREGA in 2007-08 can be predicted almost perfectly by a ‘district backwardness score’ compiled by India’s Planning Commission in 2003, at least for districts in the same state. This score is a composite index based on agricultural wages, Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe population, and agricultural productivity in the 1990s. In our analysis, we focus on such ‘non-priority’ districts during the fiscal year 2007-08, the second phase of the programme’s rollout. Figure 1 illustrates our approach. Here, districts are ordered by their within-state backwardness score, which we have suitably normalised. It is evident that this procedure perfectly predicts MNREGA coverage in 2007-08 for 13 of India’s 17 major states.

Figure 1. Non-priority districts with and without MNREGA in 2007-08

Note: Each dot represents one district. The vertical axis depicts a district’s within-state backwardness rank according to the Planning Commission’s backwardness score.

This allows us to establish a so-called regression discontinuity design (RDD), which compares MNREGA districts that were just covered in 2007-08 on the basis of their backwardness score – green dots just under the dashed equator in the figure – to ones that were not backward enough to be covered in that year by a small margin – red dots just above the equator.4,5

MNREGA: A lifeline during the agricultural off-season

To estimate the MNREGA’s welfare effects, we combine administrative MNREGA expenditure data with three National Sample Surveys that include measures of household welfare and were fielded in 2007-08. We use early research by one of us (Drèze and Oldiges, 2011) as a guide, which showed that a considerable amount of workfare employment was concentrated in just a few states (‘star states’) – among them some of India’s poorest, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan as well as Andhra Pradesh, Assam, and Tamil Nadu. Drèze and Oldiges (2011) also indicate that this employment was almost exclusively concentrated on the agricultural lean season in spring. Based on this, we study programme effects separately by agricultural season and implementation intensity.

We find increases in per capita income from workfare employment equal to about 7% of the national poverty line. Furthermore, there is no evidence of leakage of MNREGA funds in the star states during the agricultural lean season in spring. However, there is substantial leakage and – contrary to earlier studies – not even small effects on workfare income during the fall season or in other (‘non-star’) states in any season.

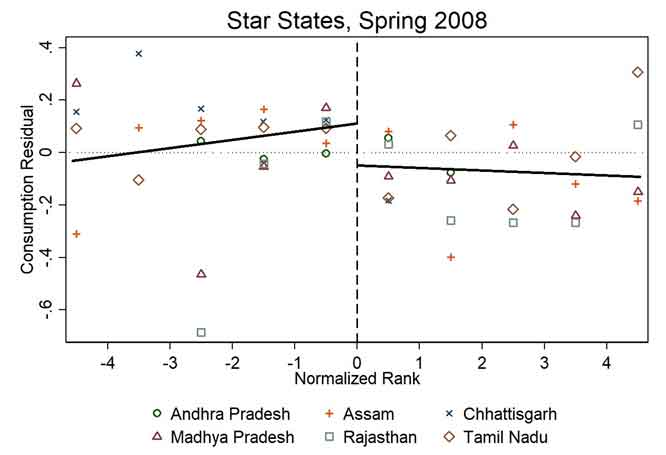

Mirroring the income effects, we find large gains in consumption in the star states during the spring season. Figure 2a illustrates that MNREGA districts in star states just to the left of the backwardness cut-off enjoyed consumption levels that are significantly higher than in districts just to the right of the cut-off, without MNREGA. The trend line depicted in this figure exhibits a jump (or ‘discontinuity’) of around 15%. This increase equals about three times the direct income gain and is accompanied by similarly large decreases in poverty. Moreover, households’ self-reported principal occupation is shifted by MNREGA with the share of the modal occupation – agricultural labour – decreasing by almost a third. We also find seasonal increases in school attendance and decreases in adolescent labour, implying that the positive welfare effects of the programme also include improvements in schooling and youth labour.

Figure 2a. Consumption in MNREGA districts in star states

Note: Each dot depicts mean consumption, suitably normalised, in one district. Districts to the left of zero have had the MNREGA at the time of the consumption survey, while districts to the right had not.

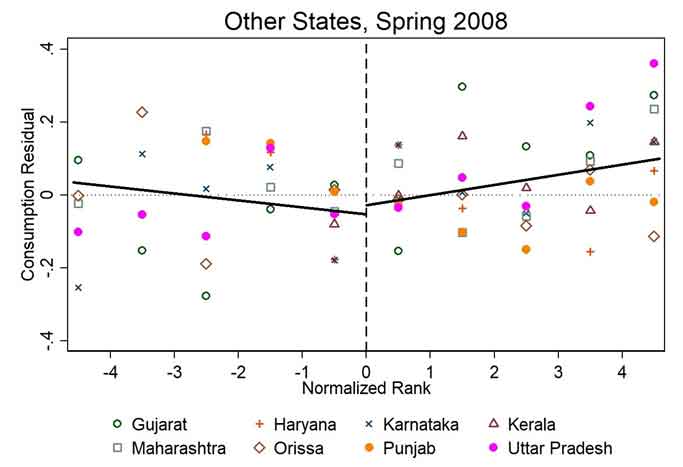

Figure 2b. Consumption in MNREGA districts in non-star states

In contrast, Figure 2b, which contains the same illustration for non-star states, shows no obvious, or at best a negative difference in consumption between districts just to the left and just to the right of the backwardness cut-off – implying no tangible MNREGA gains.6

Policy recommendation: More worksites and more workdays

Our results suggest that MNREGA can successfully reduce rural poverty and insure households against seasonal drops in employment and consumption. Through this insurance function, public employment also appears to mitigate failures in the credit market regarding households’ ability to smooth income fluctuations, which can generate positive spillovers on adolescents’ school attendance. The varied effects for both leakage and welfare by implementation intensity across states and season demonstrate, however, that an effective and sufficiently intense implementation is crucial.

We learn the following powerful lessons on implementation effectiveness and social returns: when poorly implemented, leakage is excessive and welfare effects are smaller than programme outlays, whereas leakage is small and the welfare effects close to the outlays when the implementation intensity is high. Therefore, plainly speaking, we recommend more worksites and more workdays combined with a reduction in payment delays as well as improved transparency mechanisms. These would go a long way in improving the livelihood of millions.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at state-level statutory minimum wages.

- Latest MNREGA figures are from https://nrega.nic.in.

- While researchers have previously compared all early MNREGA districts that were covered in 2007-08 to all other districts not covered in that year (for example, Imbert and Papp 2015), we argue that such comparisons are problematic. The main reason is that there are numerous factors other than MNREGA that districts in these two groups might have been differentially exposed to – including simultaneously implemented, geographically targeted welfare programmes such as the Backward Regions Grant Fund (BRGF) inaugurated in 2007, all of whose districts also received MNREGA by 2007.

- Such RDDs have been very popular in applied economics for estimating causal programme effects because they recover the true average effect of a policy intervention whenever the assignment of programme status is driven by a pre-determined score and ‘as good as random’ for units (districts in our case) whose score happens to be close to the eligibility cut-off – even if a host of other, confounding things unobserved by the researcher is going on in the background. Our research design is the first one establishing an (almost) sharp RDD for MNREGA, where ‘sharp’ indicates that the programme status of a district can be predicted perfectly from its backwardness score, as in Figure 1 in the case of Andhra Pradesh, for example. Khanna and Zimmermann (2017) and Zimmermann (2020) also use the Planning Commission’s backwardness score to establish an RDD. They do not eliminate priority districts, however, with the consequence that their RDD is ‘fuzzy’, as a district’s backwardness score only imperfectly predicts its MNREGA coverage status in 2007-08.

- While we hope that our research design better isolates MNREGA’s effects from other factors that have affected India’s districts differentially than previous research, this figure also illustrates some limitations of our approach. First, strictly speaking, our results are valid only for the subset of ‘non-priority’ districts, a label which applies to roughly every other district in India. Second, compared to approaches that use all 640 districts, our estimation samples comprise only districts on the margin of being covered by the MNREGA in 2007-08, and hence programme effects are less precisely estimated.

- On the downside, our empirical approach lacks precision to come to definite conclusions regarding some passionately disputed topics surrounding MNREGA, such as the crowding out of agricultural work by MNREGA worksites, upward pressures on agricultural wage rates, or the longer-term contributions of the assets created by MNREGA to the village economies.

Further Reading

- Besley, Timothy and Stephen Coate (1992), “Workfare vs. Welfare: Incentive Arguments for Work Requirements in Poverty Alleviation Programs”, American Economic Review, 82(1): 249–61.

- Deininger, Klaus and Yanyan Liu (2019), “Heterogeneous Welfare Impacts of National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh, India”, World Development, 117: 98–111.

- Drèze, J and C Oldiges (2011), ‘Employment Guarantee: The Official Picture’, In R Khera (ed.), The Battle for Employment Guarantee, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

- Drèze, J (2020), ‘The need for a million worksites now’, The Hindu, May 25.

- Gehrke, Esther and Renate Hartwig (2018), “Productive Effects of Public Works Programs: What do We Know? What Should We Know?”, World Development, 107: 111–124.

- Government of India (2005), ‘The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act’, Gazette of India, September 7.

- Imbert, Clement and John Papp (2015), “Labour Market Effects of Social Programs: Evidence from India’s Employment Guarantee” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(2): 233–63.

- Khanna, Gaurav and Laura Zimmermann (2017), “Guns and butter? Fighting violence with the promise of development”, Journal of Development Economics, 124: 120–141.

- Klonner, S and C Oldiges (2019), ‘The Welfare Effects of India’s Rural Employment Guarantee’, OPHI Working Paper 129, University of Oxford.

- Lal, R, S Miller, M Lieuw-Kie-Song and D Kostzer (2010), ‘Public Works and Employment Programmes: Towards a Long-Term Development Approach’, Working Paper No. 66, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, Brasilia.

- Ranaware, Krushna, Upasak Das, Ashwini Kulkarni and Sudha Narayanan (2015), “MGNREGA Works and Their Impacts”, Economic & Political Weekly, 50(13): 53–61.

- Ravi, Shamika and Monika Engler (2015), “Workfare as an Effective Way to Fight Poverty: The Case of India’s NREGS”, World Development, 67: 57 – 71.

- Subbarao, K (2003), ‘Systemic Shocks and Social Protection: Role and Effectiveness of Public Works Programs’, Africa Region Human Development Working Paper Series, World Bank, Washington DC.

- World Bank (2013), ‘World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity - Managing Risk for Development’, Washington DC.

- Zimmermann, L (2020), ‘Why Guarantee Employment? Evidence from a Large Indian Public-Works Program’, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 504.

16 December, 2020

16 December, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.