Liquidity regulation – quantity-based requirements mandating banks to maintain enough high-quality assets to meet short-term obligations during periods of stress – is a long-standing policy tool of the RBI to maintain financial stability. Examining the dynamic effects of liquidity requirements in India on key economic outcomes, this article recommends revisiting the regulation architecture such that financial stability does not come at the cost of economic progress.

India’s banking system has historically operated under a stringent liquidity regime. For large parts of its history, this regime was anchored by the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) – a quantity-based requirement mandating banks to maintain a minimum share of their net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) in the form of cash, gold, or unencumbered approved securities (typically government bonds, both long- and short-term).

Since 2015, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has further strengthened its liquidity regulation framework with the introduction of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), following the recommendations of the Basel III regulatory framework in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Emphasising both the quality and liquidity of assets, the LCR requires banks to maintain a stock of High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) at least equal to expected net cash outflows over a 30-day stress period.1 But this raises a critical policy dilemma: while liquidity mandates such as the SLR and LCR are meant to safeguard financial stability, they may also impede credit provision and slow economic growth. In other words, the very rules designed to keep banks safe might be holding back the economy.

This trade-off between stability and growth is central to how liquidity regulations influence financial intermediation in emerging markets like India. Yet, despite their widespread adoption, we know relatively little about their broader macroeconomic consequences. In new research, I seek to address this gap by examining the dynamic effects of liquidity requirements in India on key bank and macroeconomic outcomes. Specifically, I focus on the long-standing SLR, leveraging historical variation in the regulation to identify causal effects.2

SLR: Between prudential aims and a chequered legacy

Liquidity regulations, including instruments like the SLR and LCR, are implemented to ensure that banks maintain enough high-quality liquid assetsto meet short-term obligations during periods of stress. In principle, such rules prevent liquidity mismatches and promote financial stability.

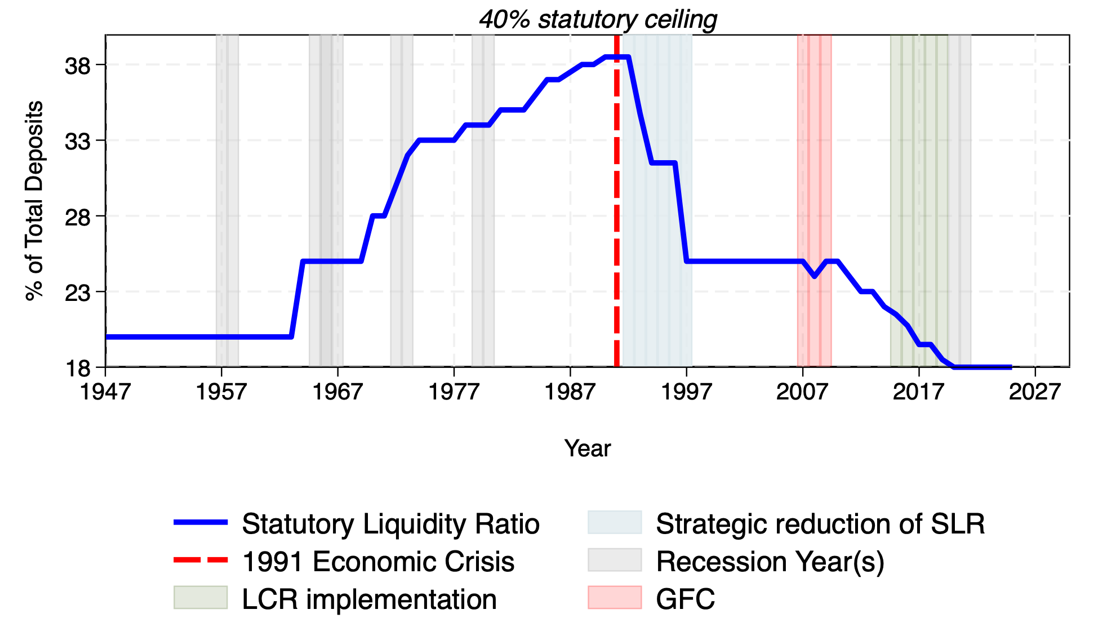

In India, however, the SLR has historically served multiple roles beyond prudential regulation. Until the early 1990s, the SLR was frequently adjusted upwards to ensure that the banking sector financed the government’s borrowing needs (Figure 1). At its peak, the mandated ratio exceeded 38% of banks’ NDTL. Though the SLR has since declined and the LCR has been introduced in line with Basel III norms, the SLR remains high by international standards and continues to shape the structure of bank balance sheets (Suvarna 2025).

Figure 1. Adjustments in the Statutory Liquidity Ratio in India

Assessing the macroeconomic impact of SLR

To measure causal effects of SLR, I develop a “narrative identification approach” to isolate episodes of exogenous changes in the SLR. These include policy adjustments motivated by either government intervention, regulatory reforms, or long-term structural motives. I find 12 such events (eight tightening and four loosening actions) between 1951 and 2023, which are unrelated to prevailing macroeconomic and financial conditions. These policy ‘shocks’ are then used to quantify the impact of liquidity regulation on the wider economy. Figure 2 presents the main results.

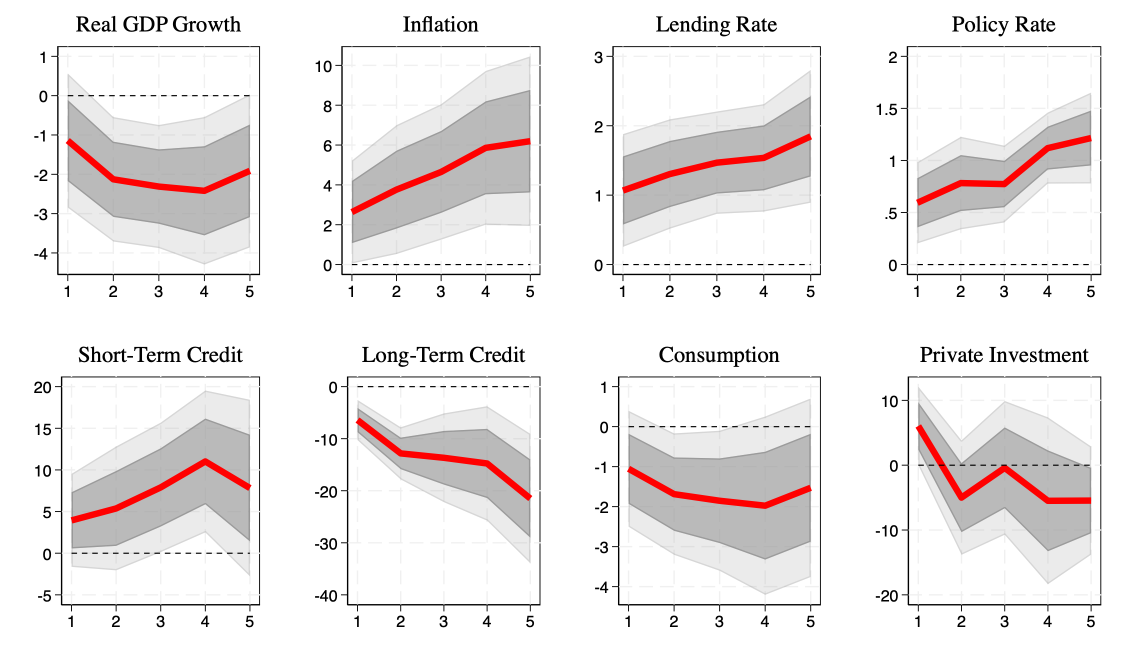

Figure 2. Dynamic impact of SLR on select bank and macroeconomic indicators

Notes: (i) This figure illustrates the estimated impact of a one percentage point increase in the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) on selected banking and macroeconomic indicators over a five-year horizon. (ii) The horizontal axis denotes the response horizon (in years), and the vertical axis shows the magnitude of the response. (iii) Lending and policy rates are expressed in percentage points, while all other variables are reported in percentage terms. (iv) Shaded areas represent 68% (light grey) and 90% (dark grey) confidence intervals. A confidence interval indicates that if the study was repeated many times, the true effect would fall within this range in 68% or 90% of the cases, respectively.

The findings point to a clear trade-off: (i) A tightening of the SLR leads to a decline in aggregate output in the medium run. (ii) Inflation, however, rises over time, prompting the central bank to respond with higher policy rates (iii) Bank balance sheets adjust, with a reallocation of assets away from longer-term loans to short-term credit and liquid assets (iv) Consumption falls significantly, while investment remains largely unaffected.

Together, these effects suggest that while overall credit supply may remain stable following an SLR tightening, banks tend to reallocate lending toward shorter-term credit. This shift can disproportionately affect households and small businesses reliant on longer-term financing, even as investment activity remains largely unchanged.

Notably, I find that banks increasingly turned to the RBI for liquidity support following an SLR hike, particularly during the period before interest rate deregulation, when their capacity to attract deposits was severely constrained. While this paradox – where tighter liquidity rules increase dependence on the central bank – is specific to the administered interest rate regime prior to liberalisation, it is echoed in recent trends, as banks once again struggle to mobilise deposits and increasingly rely on RBI and the money market for liquidity support (Vyas 2024).

Rethinking the design of liquidity regulation

The policy implications are clear: While liquidity regulations play a critical role in safeguarding the financial system, they must be designed with an eye toward their broader economic impact. India’s experience underscores the need to align its liquidity rules with a forward-looking regulatory framework.

One path forward is for policymakers to consider making liquidity requirements counter-cyclical. During periods of economic slowdown, for instance, temporarily relaxing liquidity mandates could ease credit constraints and support recovery. Conversely, tightening liquidity buffer requirements in boom periods can help build resilience.

Additionally, the interaction between liquidity regulation and monetary policy deserves greater attention. If liquidity rules systematically tighten credit conditions, they may complicate the transmission of monetary policy and require greater intervention from the central bank.

Finally, the continued coexistence of the SLR and LCR warrants reconsideration. Under the SLR, banks can invest in longer-term government securities, diverting funds away from lending to the broader economy. However, as highlighted by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023, liquidating such securities – even if deemed safe – can result in significant losses, undermining the very objective of liquidity regulation (Smith 2023). The LCR addresses this concern more directly, as it accounts for both the safety and market liquidity of assets, and allows a broader set of HQLAs. Gradually phasing out the SLR could therefore free up resources for more productive lending, without compromising financial stability.3

Lessons for other emerging markets

India’s case is instructive for other emerging and developing economies grappling with similar regulatory trade-offs. Liquidity requirements are key instruments of bank regulation in many of these countries. This is evident from the IMF’s Integrated Macroprudential Policy (iMaPP) Database, which shows that emerging and developing economies account for about 65% of regulatory changes in liquidity rules since 1990 (Alam et al. 2019) – many of which have occurred in countries such as Sri Lanka, the Philippines, and Kuwait. The challenge is to ensure that these rules do not stifle financial intermediation or hinder macroeconomic stability.

As global financial conditions tighten and central banks reassess the design of macroprudential tools in the post-pandemic world, liquidity regulation is likely to receive increased scrutiny. India’s long-standing experience with instruments like the SLR offers valuable lessons on both the benefits and pitfalls of such policies.

Conclusion

Striking the right balance between financial stability and economic dynamism is no easy task. Liquidity regulations are essential to ensure the resilience of banks. But when poorly designed or misaligned with broader macroeconomic goals, they can generate frictions that slow growth and shift risk elsewhere in the system.

India’s experience shows that it is time to revisit the architecture of liquidity regulation. A forward-looking framework must be countercyclical, calibrated in conjunction with other regulatory measures such as capital requirements and monetary policy objectives, and designed to eliminate policy redundancies. Such an approach can help ensure that financial safety does not come at the cost of economic progress.

More research is needed to build the empirical foundations for better-designed liquidity rules, especially in emerging market contexts. As Allen and Gale (2017) aptly put it: "With capital regulation there is a huge literature but little agreement on the optimal level of requirements. With liquidity regulation, we do not even know what to argue about."

Notes:

- The definition of HQLA under the LCR is more expansive than that under the SLR and includes government securities, central bank reserves, and other marketable, investment-grade securities that can be readily converted to cash with minimal loss of value.

- Given that the LCR was fully implemented only in 2019, it is not yet feasible to reliably quantify its macroeconomic effects.

-

In 2017, the Department of Financial Services within the Ministry of Finance had proposed to scrap the policy altogether (see Mishra (2017)).

Further Reading

- Allen, Franklin and Douglad Gale (2017), “How Should Bank Liquidity be Regulated?”, Achieving Financial Stability: Challenges to Prudential Regulation, 11(61).

- Alam, Z, et al. (2024), “Digging Deeper—Evidence on the Effects of Macroprudential Policies from a New Database”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking.

- Sharma, MM (2025), ‘Deepak Parekh bats for SLR cut to free up more funds to lend’, MoneyControl, 23 June.

- Smith, SV (2023), ‘Bank fail: How rising interest rates paved the way for Silicon Valley Bank's collapse’, NPR, 19 March.

- Vyas, H (2024), ‘Slower deposit mobilisation may create structural issues: RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das at BFSI Summit’, The Indian Express, 19 July.

24 July, 2025

24 July, 2025

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.