During 1975-1977, the Government of India introduced a programme involving forced sterilisation of men, in order to achieve population control as a poverty alleviation measure. Leveraging the varying degree of coercion employed under the programme across districts in the country, this article finds that forced vasectomies led to an increase in violence against women – effects that persist well beyond the period of the intervention.

Since the 19th century, family planning policies have been utilised as a developmental strategy to tackle overpopulation, limited resources, and achieve economic progress and social well-being. Historically, the world's two most populated countries – China and India – resorted to coercive measures such as ‘One Child Policy’ and forced sterilisation of men, respectively, in order to address high fertility rates.

Many studies show that enforced medical programmes can provoke mistrust in medicine and institutions, and as a result harm health and the economy (Lowes and Montero 2021). However, we still do not fully understand how these programmes may also lead to discontent and violence, which is important for assessing their broader impact on society.

In new research (Singh and Vincent 2024), we investigate the impact of a male coercive sterilisation programme, carried out in India during 1976-77, on violent behaviours among men.

The programme

During the Emergency1 (1975-1977) – in part declared to fight against poverty – Prime Minister Indira Gandhi introduced a programme aimed at reducing fertility rates as a poverty alleviation measure. The programme initially offered monetary incentives to men and women who were willing to undergo sterilisation. However, to address the low achievement rates of the first year, the programme employed coercive methods for the last 10 months of its implementation, where State authorities withheld work promotions and payments of their workers until individuals who were supposed to undergo sterilisation did so and persuaded others to comply with the programme as well (for example, government school teachers being required to convince parents of students). Job loss threats were commonly used to ensure compliance. Furthermore, the government mandated sterilisation certificates for access to essential services like housing, irrigation, ration cards, and public healthcare facilities. Notably, husbands with two or more children faced significant pressure to undergo sterilisation. (Tarlo 2003, Jaffrelot and Anil 2021).

The implementation of the programme varied across the country for various reasons: some regions were more closely aligned with the political party of Indira Gandhi, while others feared political reprisal or incarceration for opposing the programme. Additionally, logistical factors such as distance from the national capital also influenced the intensity of implementation.

This aggressive family planning campaign resulted in 6.2 million men undergoing sterilisation in 1976-77, a notable increase from the 1.5 million vasectomies performed in 1975-76 when the programme only offered monetary incentives (Shah Commission of Inquiry 5-6). This programme stands as the most extensive coerced sterilisation campaign ever conducted globally.

Measuring coercion intensity

We use the rate of growth in the proportion of sterilised married couples between 1975-76 and 1976-77, as an indicator of the coercion intensity of programme implementation at the district level (Jolly 1986). A significant increase in sterilisation during 1976-77 captures the coercion element, as it signifies an increase in this specific year compared to the period when only incentives were offered (Pelras and Renk 2023).

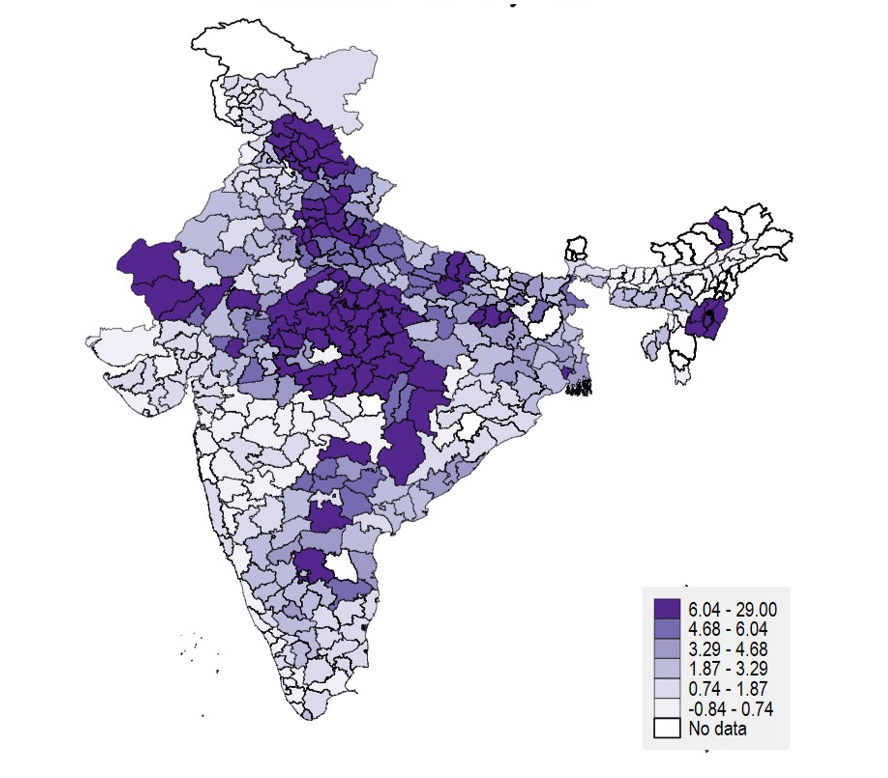

Figure 1. Coercion intensity index

Note: The figure illustrates coercion intensity, which goes from 0% to 29% and is heterogeneously dispersed throughout India.

Source: Jolly (1986)

Data and empirical strategy

We digitise crime rates at the district level in India from the National Crime Records Bureau from 1972 (the first year available) to 2013. We compare districts with low exposure to forced vasectomies, based on the political and logistical factors mentioned above, with high-exposed ones, before and after the programme, using both static and dynamic analyses.

Our empirical strategy does not rely on the randomness of the implementation. However, ‘unobservable variables’ can pose a threat to causality. For instance, when we seek to establish the causal effect of forced sterilisation on violence in a district, there may be certain characteristics of the district that led to both greater incidence of forced sterilisation as well as of sexual assaults. Hence, it may not be accurate to claim that the programme is what is causing the increase in rapes. However, we consider this possibility highly unlikely for several reasons: First, with the information available in the 1971 Indian Census and the 1971 election dataset, we investigate whether coercion implementation is linked to particular characteristic of districts – such as share of politician elected from the government’s party, number of workers, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and so on. We find that coercion intensity only correlates with a higher number of middle-school achievers, which would not predict more violence.

Second, as our ‘treatment’ variable (growth rate between sterilisations before and during the programme) is continuous and precise, it is statistically unlikely that it reflects another variable to the same extent. As the size of police forces could impact both the implementation of the programme and the number of crimes reported, we also account for police forces size at the state level.

Finally, we note that other programmes launched during the Emergency period, such as banning dowry, eradicating castes, tree planting and promoting literacy, lacked the same intensity or effectiveness or are unlikely to have impacted violence.

Forced vasectomies lead to an increase in violence against women

Our research reveals that the level of coercion employed does not have a significant impact on overall crime rates, property crimes, or incidents of rioting. However, it does lead to a notable increase in violence against women, primarily attributed to a surge in reported cases of rape2. Our estimates indicate a 22% rise in reported rapes in the average district with coercion intensity of 5.1%, following the implementation of the programme.

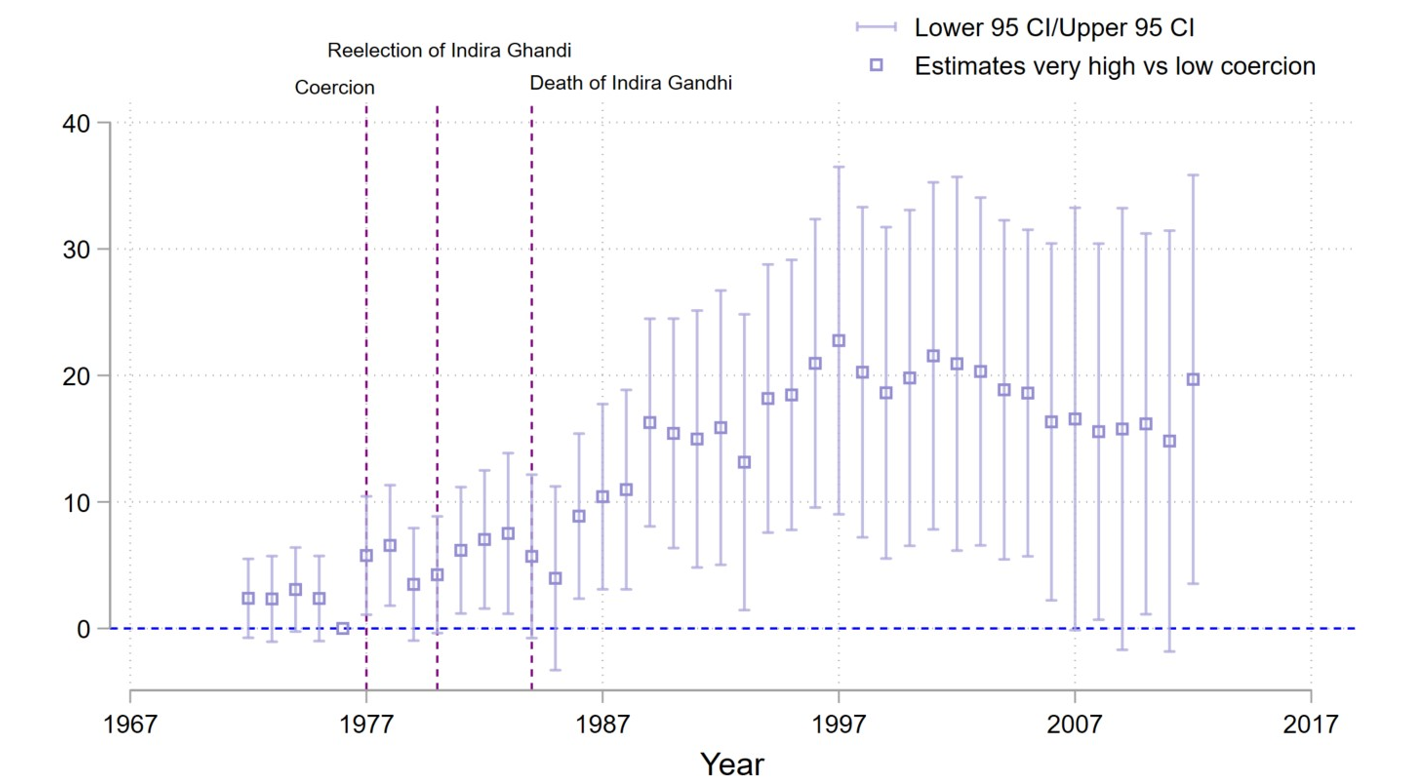

Figure 2 illustrates that the influence on reported rapes continues over time, particularly in districts with higher levels of coercion (above 6%), which correspond to the top 25% of high-coercion districts. This effect remains statistically significant until the conclusion of our analysis in 2013.

Figure 2. Incidence of rape for the 25% most-exposed districts, 1972-2013

Note: i) The dependent variable (on the vertical axis) is the number of rapes per 1 million inhabitants ii) A 95% confidence interval (CI) is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects. Specifically, it means that if the study was repeated over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

During this period, 95% of reported rape perpetrators in India were men aged 18 to 50. Some of them may not have been the primary targets of the sterilisation programme, as the average age of men sterilised in 1976-77 was 35. These results suggest a potential cultural transmission of violence.

Building on insights from economic, anthropological, and psychological literature, we propose several potential pathways through which a forced male sterilisation programme could impact violence against women: i) Reduced fertility rates may lead to shifts in gender roles and ratios; ii) The sterilisation procedure itself could induce trauma in men; and iii) It might influence perceptions of masculinity, potentially triggering violent behaviour among men.

Coercion intensity not associated with a decline in fertility

We utilise data from the National Sample Surveys of 1986-87 to investigate the impact of coercion intensity on birth rates. Comparing households in low- versus high-exposure districts, we categorise households based on the number of children they had before 1977, as those with two or more children were particularly targeted during the programme. Surprisingly, our findings reveal that an increase in coercion intensity leads to a very slight positive uptick in fertility post 1976, rather than a decrease. This trend is especially noticeable among families without a son, or large families.

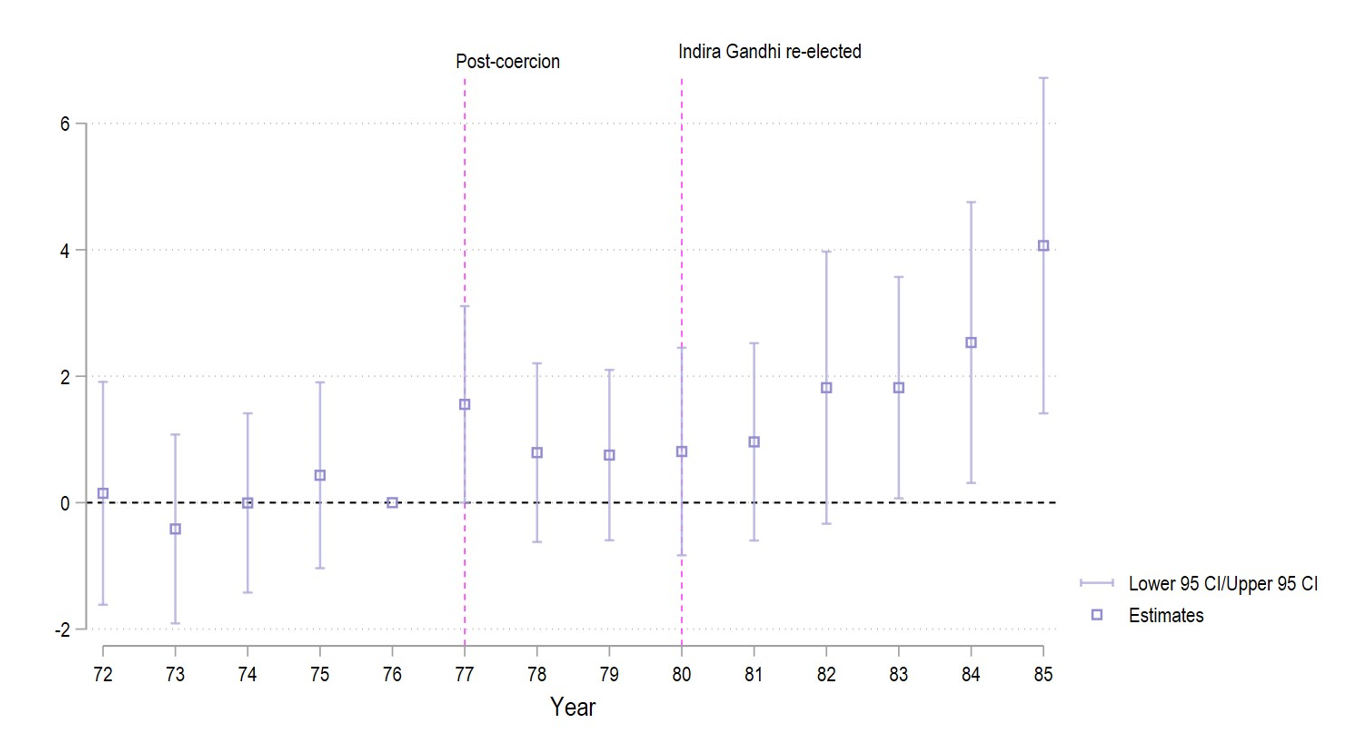

In addition, Figure 3 reveals an increase in fertility beginning in 1980, coinciding with Indira Gandhi's re-election and a period marked by escalated tensions in India. It suggests that households residing in districts previously impacted by the forced vasectomies of 1976-77 might have held apprehensions regarding the potential reinstatement of such initiatives, prompting them to expand their families as a precautionary step.

Figure 3. Births per household, 1972-1985

A reaction to trauma or threat against masculinity?

The forced sterilisation campaign, mostly targeting men for population control, is documented to have posed a challenge to traditional masculinity, potentially resulting in feelings of emasculation (Scott 2014). A large body of psychological literature has documented the connection between manhood and the inclination towards aggression and violence against women (Bosson et al. 2019).

Furthermore, there are extensive psychological connections linking male violence towards women to experiences of childhood or adulthood trauma (Oehme et al. 2012, Mrug et al. 2016). Although our findings do not directly identify the age of perpetrators of crimes, data indicate that most rape cases in India are committed by younger men, who would have been children or adolescents during the Emergency. Witnessing threats to older males and/or violence at home during that time may have been traumatic, potentially leading to increased violence in adulthood.

In exploring this hypothesis, we posit that districts where such channels were operative, would exhibit more harmful gender biases. We use data from the 1999 Demographic and Health Surveys – the first household-level survey at the district level in India to include questions about domestic violence – to examine the hypothesis. Our findings demonstrate a positive correlation between the intensity of coercion and elevated instances and acceptance of intimate partner violence (IPV), alongside diminished bargaining power among women. These results indicate a prevalence of more adverse attitudes towards women in 1999 within districts that witnessed heightened coercion levels in 1977.

Study limitations, and policy implications

Our study is limited by data constraints, especially in identifying the specific mechanisms driving the increase in violence against women. Further investigation into factors such as mental health, perceptions, and so on, will enhance comprehension of the programme's broader impacts. Nevertheless, these results highlight an overlooked aspect concerning the consequences and persisting effects of coercive interventions, particularly those intersecting with masculinity or fertility. Given India's diverse landscape, our findings may hold relevance across different contexts.

Notes:

- For a 21-month period from 1975 to 1977 a state of emergency was declared across India. During an Emergency, the fundamental rights of Indian citizens may be suspended if required to curb internal or external threats to the nation.

- This is unlikely to have been due to a rise in reporting, rather than in the incidence of rape, for two reasons: i) the police played an important role in coercion and the most natural impact would be mistrust against them, even from women, and ii) we find that more exposed districts are correlated, in 1999, with more harmful gender norms, that seems not to encourage female empowerment.

Further Reading

- Bosson, Jennifer, Joseph Vandello, Rochelle Burnaford, Jonathan Weaver and Syeda Wasti (2009), “Precarious Manhood and Displays of Physical Aggression”, Personality Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(5): 623-634.

- Jaffrelot, C and P Anil (2021), India’s First Dictatorship, Oxford University Press.

- Jolly, KG (1986), Family Planning in India, 1969-1984: A District Level Study, Hindustan Publishing Corporation, Delhi.

- Lowes, Sara and Eduardo Montero, (2021), “The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa”, American Economic Review, 111(4): 1284-1314.

- Mrug, Sylvie, Anjana Madan and Michael Windle (2016), “Emotional Desensitization to Violence Contributes to Adolescents’ Violent Behavior”, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1): 75-86.

- Oehme, Karen, Elizabeth A Donnelly and Annelise Martin (2012), “Alcohol Abuse, PTSD, and Officer-Committed Domestic Violence”, Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 6(4): 418-430.

- Pelras, Charlotte and Andréa Renk (2023), “When sterilizations lower immunizations: The Emergency experience in India (1975–77)”, World Development, 170: 106321.

- Singh, A and S Vincent (2024), ‘Male Sterilization and Persistence of Violence: Evidence from Emergency in India’, Working Paper, HAL SHS.

- Scott, G (2014), ‘Gender and Power: Sterilisation under the Emergency in India, 1975-1977’, The North West Gender Conference, Issue 5: Constructions of Gender in Research.

- Tarlo, E (2003), Unsettling Memories: Narratives of the Emergency in Delhi, Orient Blackswan.

- The Shah Commission Final Report: General Observations (1990), Indian Journal of Public Administration, 36(3): 695-701.

08 May, 2024

08 May, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.