In the fifth and final article in the Ideas@IPF2023 series, Eichengreen, Gupta and Ahmed reveal how high levels of debt in India limit the resources available for other priorities. At the same time, they predict that there is no immediate crisis of debt sustainability, as institutional factors limit rollover risk, and interest rates have not risen with additional debt issuance. However, financial stability and sustainability risks may arise in the future, and fiscal consolidation would require lower primary deficits achieved through tax revenue generation and privatisation.

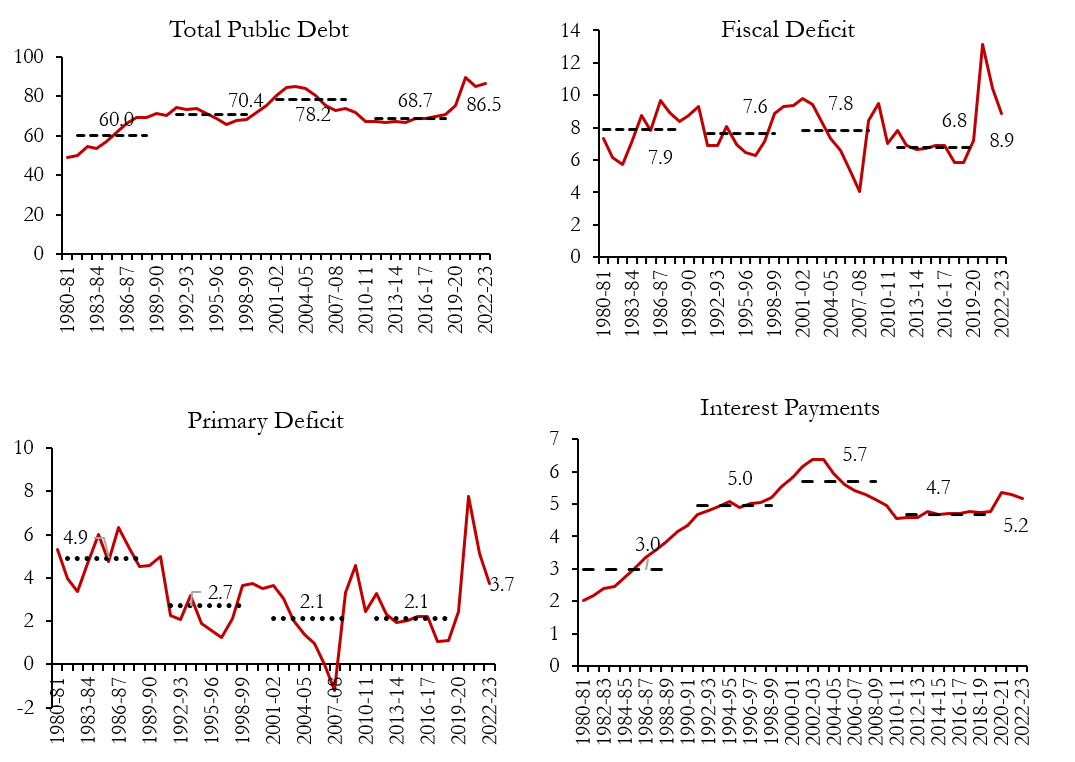

India’s public finances paint a mixed picture: its fiscal deficits and public debts were among the highest in the developing world, and its interest payment-to-GDP ratio and primary deficits were large even before the pandemic. The pandemic reinforced these trends – at their peak in FY2020-21, the debt and deficit stood at 89 and 13% of GDP respectively (Figure 1). Contingent liabilities are estimated at an additional 5% of GDP.

Figure 1. General government debt and fiscal indicators, as a percentage of GDP

Notes: i) Total public debt in India includes debt issued and other liabilities in the Public Account consisting of National Small Saving Fund (NSSF), Provident Fund, Deposit and Reserve funds, securities issued to finance subsidies on oil, food and fertilisers, etc. ii) Dashed horizontal lines are decadal averages from 1980-81 to 1989-90, 1990-91 to 1999-2000, 2000-01 to 2009-10, and 2010-11 to 2019-20, respectively.

Source: CEIC (compiled from Reserve Bank of India).

With the recovery of nominal GDP, the country’s debt and deficit ratios have fallen from these multi-decade highs. But at 84 and 9% they are still high relative to other emerging market and middle-income countries, where they average 60 and 5% respectively. While India’s debt ratio is comparable or lower than that of the advanced economies, this provides little comfort. Advanced-country governments enjoy lower interest rates and consequently have lower interest payment-to-GDP ratios. Debt-to-GDP ratios of advanced economies averaged 112% in 2022, whereas interest payments averaged 1.5% of GDP. In contrast, India pays as much as 5% of GDP in interest on debt.

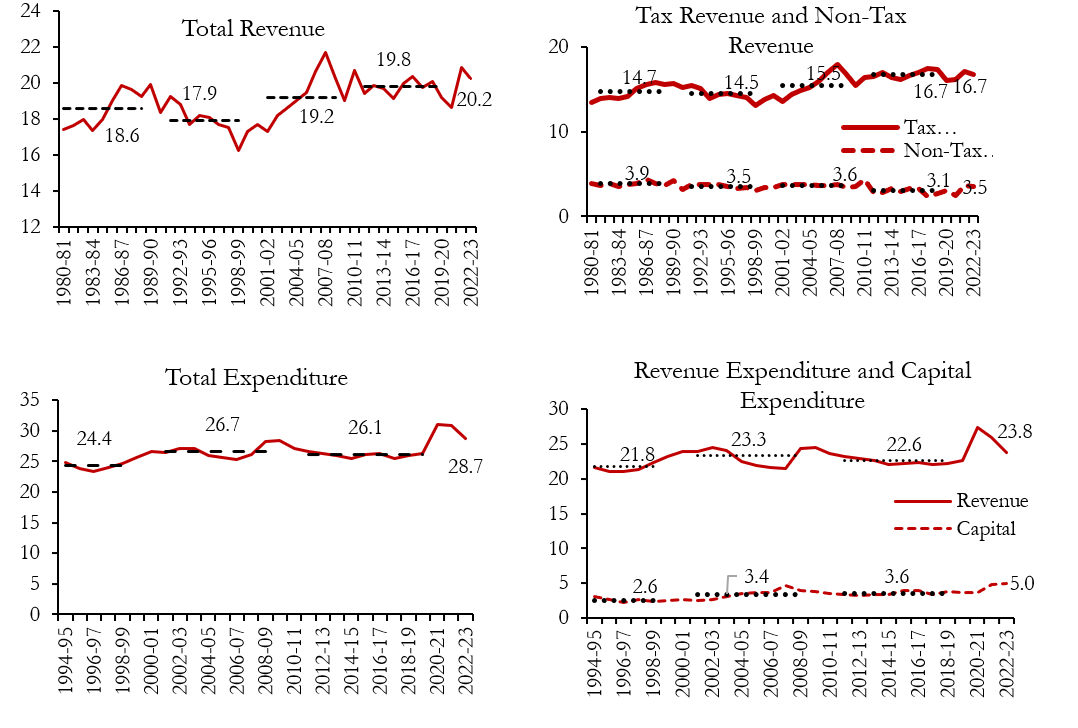

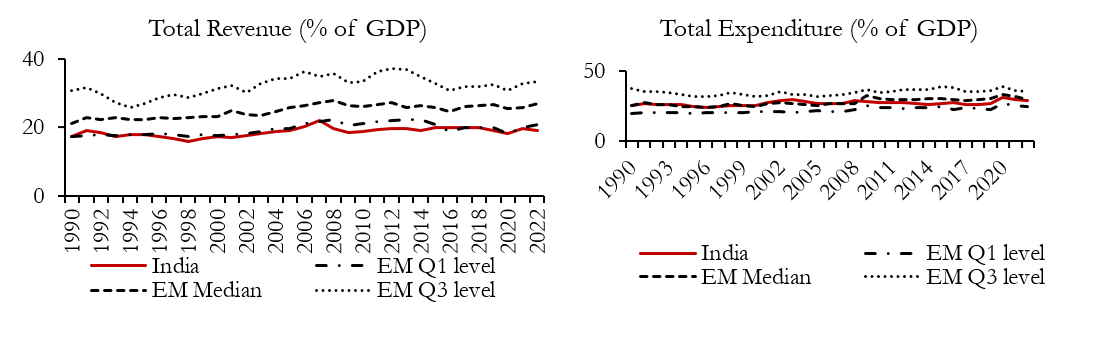

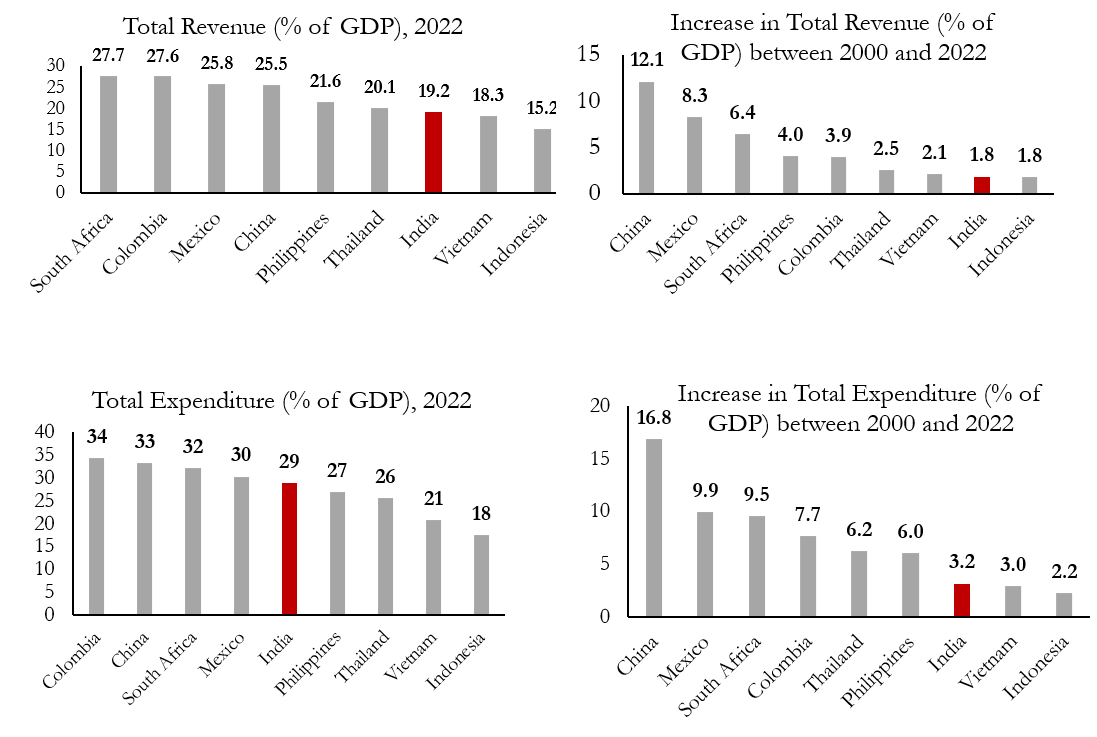

India’s deficit is thus more a problem of low revenues than one of high expenditure. The revenue-to-GDP ratio in India is below that of most other emerging markets and has seen the slowest rates of increase over the last 20 years. In contrast, the public expenditure-to-GDP ratio is not atypical and, if anything, has increased even more slowly (Figure 2). This gap has resulted in a perennially large – and growing – budget deficit compared to other emerging markets (Figure 3).

Figure 2. General government revenue and expenditure

Note: Dashed horizontal lines are decadal averages from 1980-81 to 1989-90, 1990-91 to 1999-2000, 2000-01 to 2009-10, and 2010-11 to 2019-20, respectively.

Source: CEIC (compiled from Reserve Bank of India).

Figure 3. Comparing India’s fiscal indicators with emerging market (EM) averages

Notes: i) The figures in the top row show median and interquartile range of 83 emerging market and middle-income economies (83 countries) and India. ii) The figures in the middle and bottom row compare India’s fiscal indicators with those of select emerging markets. iii) Data for India is for fiscal years.

Above, we have presented the key features of Indian public debt and expenditure vis-à-vis other emerging economies. In the article ahead, we assess the pressures on the sustainability of India’s public finances, with a focus on the next five years.

Understanding criteria for debt sustainability

A first criterion for sustainability is whether there is significant rollover risk. We find that the institutional factors, such as a captive market for public debt among state banks, private banks, insurance companies and provident funds, together with household savings, have enabled the government to fund its deficits without undue pressure on borrowing costs. In addition, the currency composition and maturity of the debt limit the rollover risk. Nearly 90% of general government debt is long-term. There has been a concerted effort to reduce rollover risk by issuing long-tenor securities. As a result, the weighted average maturity periods for both central and state government loans have been increasing. While the average maturity of public debt has risen, yields have declined, if only slightly: the general government weighted average coupon fell from 8% in FY2011-12 to 7.3% in FY2022-23.

A second criterion for sustainability is whether the debt ratio will remain stable. Our projections confirm that, under reasonable assumptions, the debt ratio will remain broadly stable (Table 1). This stability rests on the assumption of a largely unchanged primary budget deficit and a favourable growth rate-interest rate differential, the latter reflecting India’s positive growth prospects and also institutional factors limiting upward pressure on interest rates. The institutional factors in question include a captive market for public debt among state banks, private banks, insurance companies and provident funds. Together with household savings, these have enabled the government to fund its deficits without undue pressure on borrowing costs.

In FY2000-01, about 13.5% percent of central government debt was issued externally. Since then, there has since been a steady decline in the share of external debt, which stood at just 3.7% in FY2021-22. The remainder is long-term instruments, concessional, and owed to multilateral and bilateral investors (amounting to 3% of the total debt). Holdings of foreign institutional investors are just 1% of the total debt. Foreign banks hold negligible quantities of Indian government debt. Debt denominated in foreign currency dropped from about 10% of the total in FY2002-03 to 4.3% in FY2020-21. Consequently, the debt portfolio is largely insulated from currency risk.

Table 1. Evolution of general government debt-to-GDP ratio

|

Scenarios |

Debt level in FY2022-23 |

Primary deficit |

Real GDP growth |

Real interest rate |

Change in debt in first year |

Cumulative change in debt in next five years |

|

Baseline: Past 10-year averages |

86.5 |

2.9 |

5.7 |

2.8 |

0.5 |

2.2 |

|

Higher real GDP growth rate |

86.5 |

2.9 |

7.9 |

2.8 |

-1.2 |

-5.5 |

|

Lower primary deficit |

86.5 |

1.9 |

5.7 |

2.8 |

-0.5 |

-2.6 |

|

Baseline plus contingent liabilities absorbed (1 percentage point of GDP) each year |

86.5 |

2.9 |

5.7 |

2.8 |

1.5 |

6.9 |

|

Baseline with higher real GDP growth rate and lower primary deficit |

86.5 |

1.9 |

7.9 |

2.8 |

-2.2 |

-10.1 |

Source: For FY2022-23, estimates of the level of debt are from the Economic Survey. Projections start from FY2023-24.

In sum, India’s general government debt-to-GDP ratio, which is high by emerging market standards, is unlikely to decline significantly in the next five years. In the best-case scenario, it might fall from its current level of some 90% of GDP to 80% of GDP, but even under optimistic assumptions, the debt-to-GDP ratio will remain high relative to comparator countries. Less rosy scenarios are also possible. Smaller primary budget deficits will be difficult to achieve, given pressure for social and infrastructure spending and the difficulty of boosting tax revenues. Faster growth rates or lower interest rates would also be difficult to achieve.

Costs and risks associated with India’s high debt and deficits

First, interest payments absorb resources, and limiting their availability for other economic and social purposes. In India, interest payments exceed 25% of general government revenues. At 5% of GDP, this is roughly twice the emerging market and developing-country average

Second, available fiscal resources leave no room for meeting emerging priorities, notably climate change abatement and adaptation, and the green transition.

Third, debt dynamics leave little room for responding to shocks, such as declining rates of domestic and global growth. India was not strongly constrained in responding to Covid-19; it reacted with a fiscal stimulus of Rs. 20 trillion, or roughly 9% of GDP. But at some point, responding to shocks in this way will begin to show up in interest rates, especially as regulations that encourage investments in bonds issued by insurance companies, provident funds and banks are progressively relaxed. Eventually, this will throw debt sustainability into doubt. Conversely, maintaining debt sustainability in the face of such shocks will leave the government countercyclically constrained, amplifying cycles.

Fourth, high government debt creates the potential for financial stability risks. For the moment, such risks remain limited. Banks are required to hold government securities in order to satisfy their Statutory Liquidity Ratios (SLR). Risks to their balance sheets can therefore develop with the repricing of these assets when interest rates rise. For the moment, India may be able to place most of its debt with ‘patient’ domestic investors. But if this becomes less true going forward, run risk – and therefore volatility – will rise.

Path ahead for debt consolidation, in theory and reality

In purely mathematical terms, India could bring down its debt to 70% of GDP through a combination of lower primary deficits, higher inflation, and faster GDP growth. A percentage point increase each in growth and inflation and a percentage point reduction in the primary deficit would achieve this in five years. The requisite changes could be achieved through an amalgam of the following factors:

i) Raising additional revenue through higher tax, non-tax, and privatisation receipts: Along with better tax administration and digitalisation, recent tax reforms (notably the introduction of a uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017) have succeeded in modestly boosting revenue growth. Yet in a fast-growing economy, where nominal GDP has been growing on average at 11-12%, the rate of tax-revenue growth still has not exceeded that of GDP growth (in contrast to other fast-growing emerging markets). More could be done along these lines, both through additional digitisation and administrative streamlining, and through the adoption and better administration of new taxes, such as a tax on property at the state or central government level (though the political economy of the latter is obviously challenging).

ii) Continuing to re-orient spending toward capacity- and infrastructure-enhancing investment that promises to further boost GDP and revenues.

iii) Limiting contingent liabilities, which have been a chronic problem at the state level.

But imagining sharp changes along these lines borders on wishful thinking. Economic and social development will require additional spending on health and education. The government will have to contribute significantly to the country’s decarbonisation and climate-change-adaptation investments, which are large by international standards. Eventually, interest rates will adjust upward in response to inflation, eliminating any favourable debt-consolidation effects. As a result of these factors, India will almost certainly be living with high public debt for years to come.

This is a summary of a preliminary draft paper prepared for the NCAER India Policy Forum 2023.

17 July, 2023

17 July, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.