Introduced in 2013, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) brought about fundamental reforms in the public distribution system (PDS) and most importantly, declared a legal ‘right to food’. Based on a primary survey in Bihar, Odisha, and Uttar Pradesh, this article traces the changes in the PDS post NFSA, and during the Covid-19 crisis.

Introduced in 2013, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) – the largest food-based social safety-net programme in the world – covers 800 million individuals (75% of the rural population, and 50% of the urban population) and costs Rs. 4,400 billion (as of 2017) (Bhattacharya et al. 2017). The Public Distribution System (PDS) is the apparatus for implementing the NFSA though its nationwide network of fair-price shops (FPS), making highly subsidised foodgrains available to citizens.

Before the NFSA, households were classified into three categories: above poverty line (APL), below poverty line (BPL), and poorest of the poor as categorised under the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) – with differential entitlements1. The NFSA categorised households into two groups: NFSA-priority households (NFSA-PHH) and AAY. The allowance of foodgrains were set at 5 kilograms (kg) per person for the PHH category, and 35 kg per household for AAY. Prices were fixed at Rs. 3, 2, and 1 per kg for rice, wheat, and coarse grains, respectively. The most important provision of the NFSA was, that it set a legal ‘right to food’ – the failure to provide the quota of entitled food makes the government liable for compensation (Bezbaruah 2013). The provisioning and strengthening of grievance redressal systems (GRS) was among the other fundamental and institutional reforms brought about by the NFSA.

Access to PDS post-NFSA and during the Covid-19 pandemic

Notwithstanding large-scale changes in the PDS due to the NFSA, the implications on its beneficiaries remain largely unknown. One reason for this is the lack of data, as the National Sample Surveys (NSS) (Consumer Expenditure Surveys) were not administered after the 68th round in 2011. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, PDS was entrusted with meeting the food security needs – expanding its portfolio and providing free grains. However, how well PDS delivered through the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY)2 as Covid-19 relief, has not been assessed. In recent research (Roy et al. 2021), we seek to fill these gaps by gauging the situation post-NFSA and during Covid-19, based on primary surveys in Bihar, Odisha, and Eastern Uttar Pradesh (EUP)3.

This study partly builds on the sample and research conducted in 2014 (Pradhan 2018), when the NFSA had not yet been rolled out in these states. The NFSA was gradually rolled out in phases, starting March 2014 (Bihar), November 2015 (Odisha), and March 2016 (UP) (Puri 2017). Pradhan (2018) shows that households have varied experiences with PDS not only with respect to quantities, prices, and the quality of grains, but also in services rendered at FPS, even when subject to the same eligibility criteria of income and location. In terms of actual uptake and experiences, differences existed based on economic status and gender (Pradhan and Roy 2019).

In a recent survey, we collect information to compare pre- and post-NFSA experiences in terms of accessing PDS and utilising entitlements, and assess whether respondents are aware of the changes in PDS entitlements due to the NFSA, by household category, and state-specific adjustments. The survey also looks at PDS delivery during Covid-19, and awareness of and preferences for reforms like One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC)4, which were proposed earlier but implemented as part of the India’s Covid-19 response. During the survey period, ONORC was still a work-in-progress.

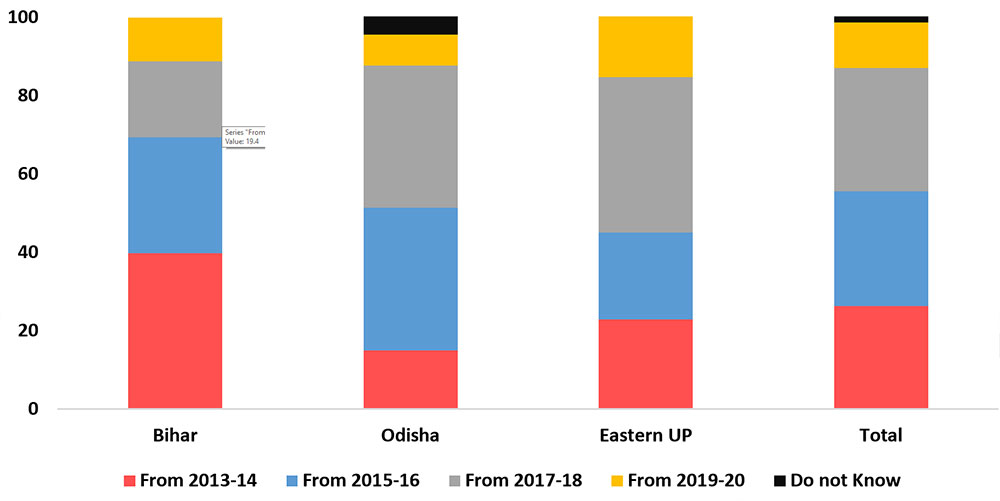

Eligibility of services: Access to ration cards post-NFSA

In our survey sample, several respondents who belonged to the AAY category in the pre-NFSA period were shifted to PHH list under the NFSA (69% in Bihar), and many without a ration card transitioned to PHH (95% in Bihar, and 93% in Odisha and UP). Figure 1 shows this transition, the inner circle represents the percentage of those originally in the BPL, APL, AAY, ANP (Annapurna, which includes low-income senior citizens), and no card categories, and their shift (outer circle) to NFSA-PHH and NFSA-AAY. This transition happened at a different pace across states (Figure 2). About 40% in Bihar and 23% in UP (15% in EUP) received PHH cards in 2013-14. Most of the transition in Odisha occurred in 2015-16 (36%) and 2017-18 (36%). In EUP, 40% received PHH cards in 2017-18.

Figure 1. Transition of ration cardholders from pre- to post-NFSA card categories

Figure 2. Year of transition to NFSA cards (%)

The delay in rollout of NFSA cards was due to a delay in incorporating the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) for the selection of eligible households (Dreze et al. 2019), exclusion errors, and widespread lack of awareness about NFSA provisions and eligibility requirements. In Odisha, beneficiaries were asked to self-declare eligibility by filling a form, which resulted in delays. Those in charge of this paperwork were under-informed and not capable of discharging these responsibilities efficiently. Moreover, with the transition to per-capita entitlements, regular, and reliable updating of ration cards became necessary and this proved cumbersome.

Allocations: Quantity and price of foodgrains post-NFSA

With per-capita entitlement, bigger families gained in terms of quantity of grains received while smaller families lost out. Despite some time having elapsed since the introduction of the NFSA, it is surprising that many remain unaware about specific entitlements, both in terms of quantity and price (30% in Bihar, 22% in EUP, and 17% in Odisha).

With the NFSA, prices of foodgrains also changed: in Odisha, the rice price was lower than the central government’s issue price. Sixty one per cent cardholders perceive to have paid a higher price for rice pre-NFSA, as the state scheme was not active then. In the post-NFSA regime, about 11% cardholders in Odisha perceive to have paid a higher price for rice. Even after the state government further subsidised prices, about 22% of the ration cardholders in Odisha perceive paying the same price pre-and post-NSFA. This shows lack of awareness and understanding of NFSA in these states.

However, in Bihar and EUP, 27% and 18%, respectively, perceive post-NFSA expenses to be higher. Furthermore, about 39% in Bihar and 38% in EUP, report paying the same price post-NFSA as they were pre-NFSA.

About 43% households in Bihar and EUP and 91% in Odisha are aware about the mandated price of rice. Awareness of the quantity of rice and wheat mandated by the government is higher than awareness about the price (70% Bihar, 78% EUP, and 83% Odisha). Unaware households are prone to entitlement snatching and lower fetching of entitlements. These beneficiaries report lower quantities or higher prices than mandated.

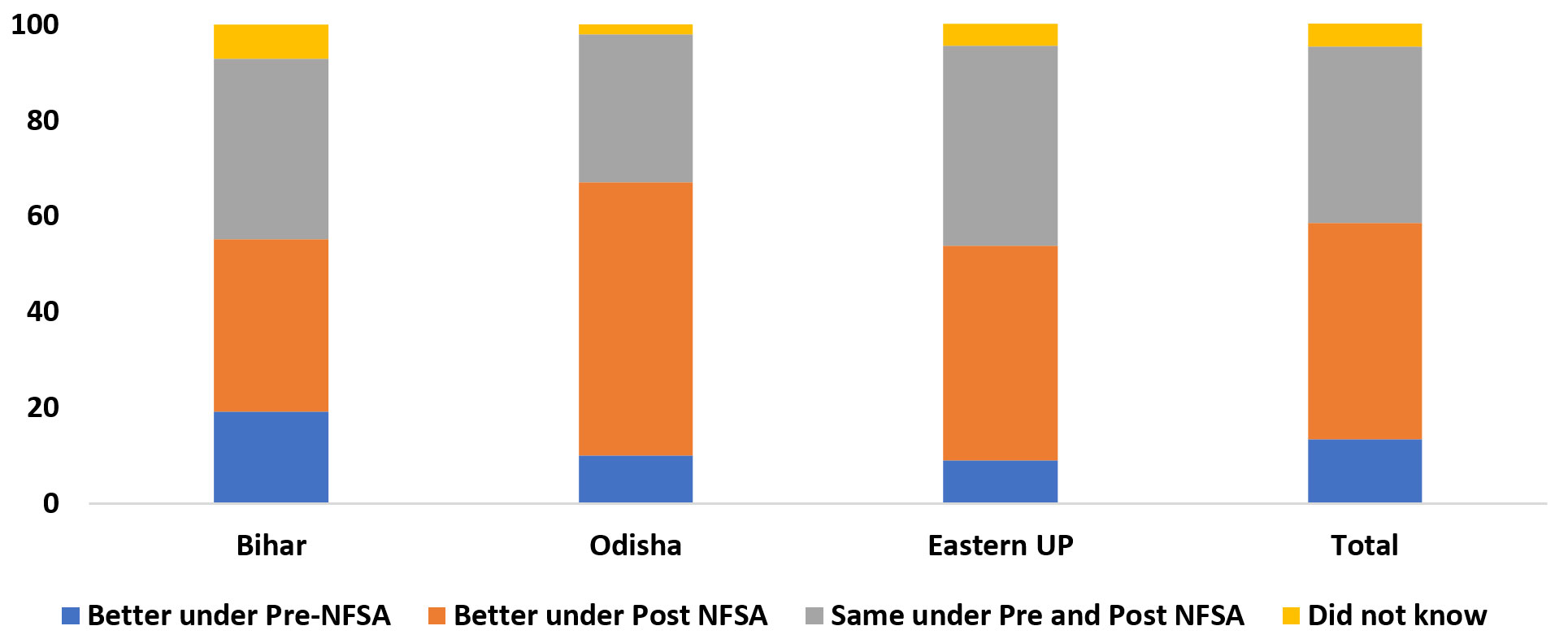

Changes in grain quality post-NFSA

As arbitrage opportunities have changed, new forms of discrimination might have emerged in PDS in terms of the quality of grains, and standard of services (waiting time and dealer-client behaviour)5. While quantity- and price-based discrimination are easily and commonly discerned, quality of grains and of services are imperfectly observed and difficult to challenge. Figure 3 presents the quality assessments pre-and post-NFSA.

Figure 3. Quality comparison of PDS rice (%)

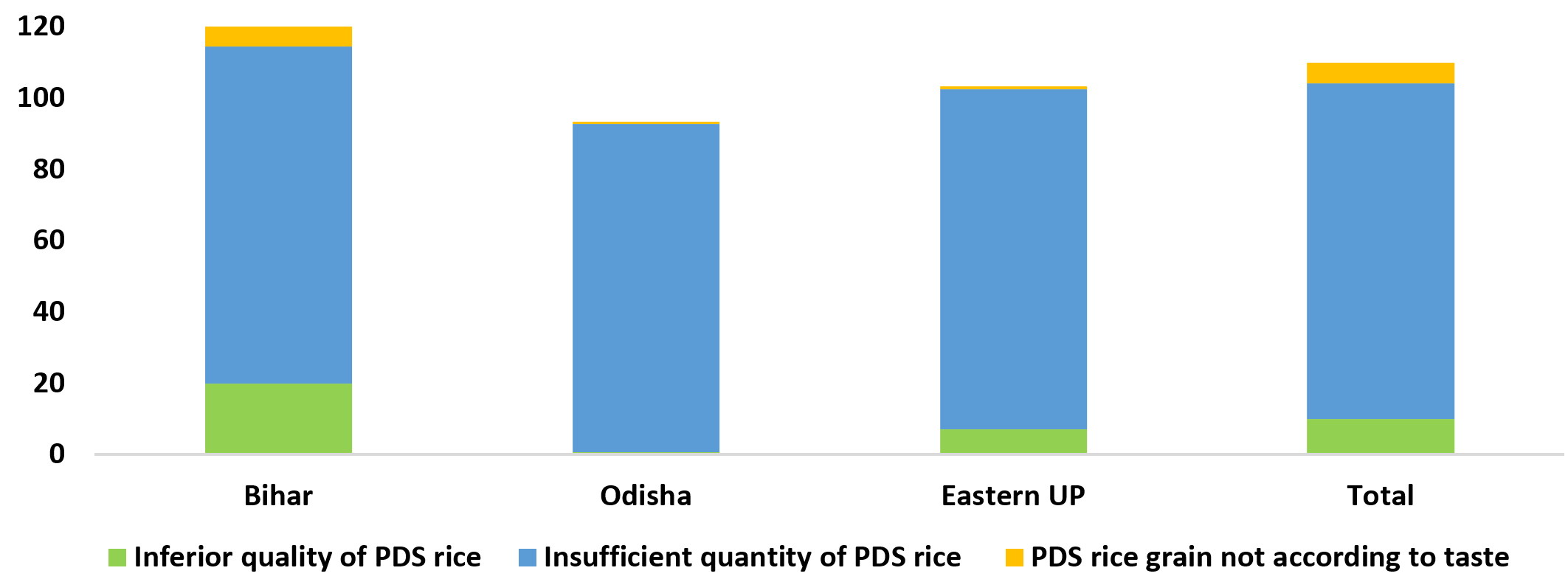

Further, we assess whether households’ requirements were fully met by PDS or if they need supplementary market purchases due to a shortfall in quantity or inferior quality. The majority (52%) supplement PDS even post-NFSA (Figure 4). In Bihar, 20% of the respondents say they are not satisfied with PDS rice quality and for 15%, grain variety is ‘unacceptable’6.

Figure 4. Reasons for supplementing PDS rice with market purchase

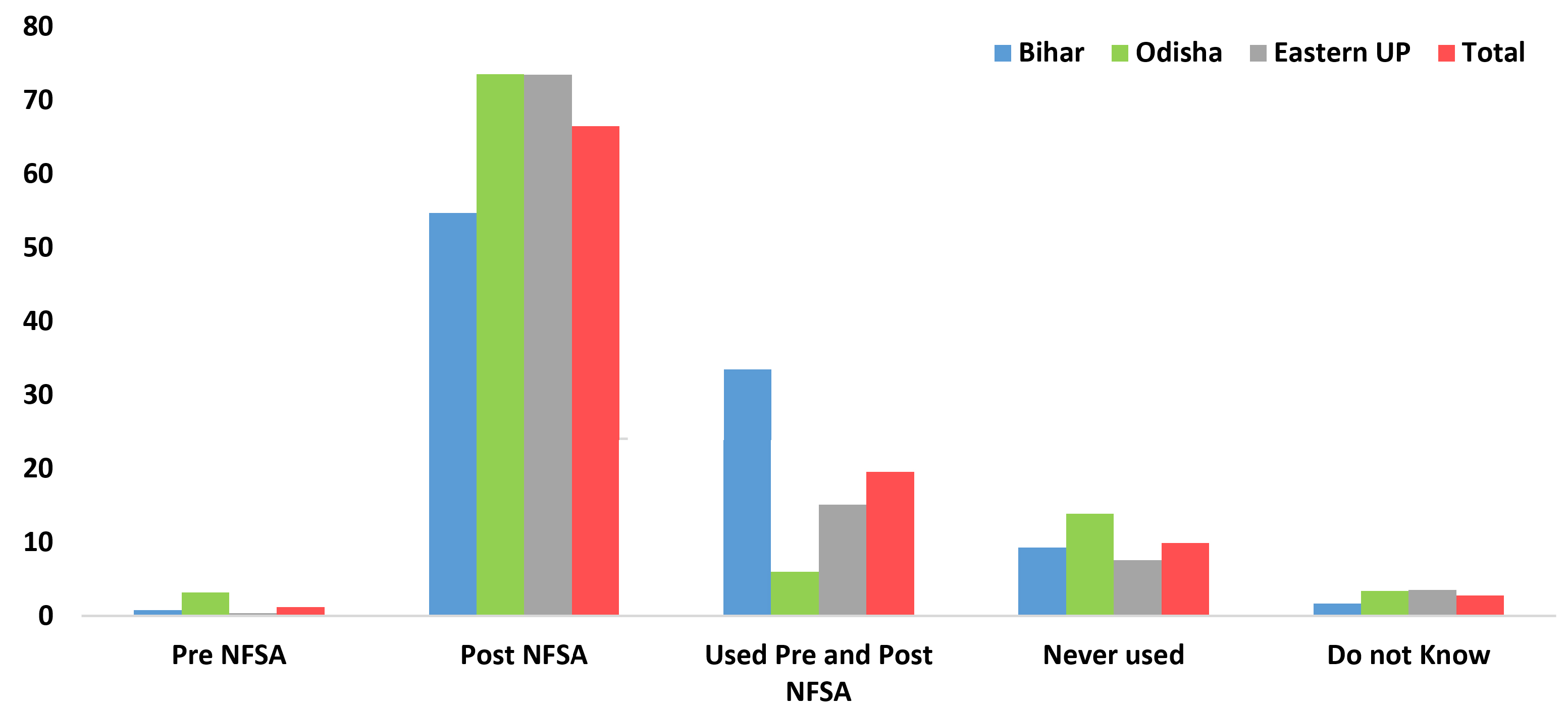

PDS delivery services pre- and post-NFSA

Over the years, PDS delivery system has been known to be susceptible to leakages due to maladministration and, in some cases, outright theft. Bihar lags substantially in terms of the operational credibility of PDS (Choithani and Pritchard 2015). A similar story emerges post-NFSA (Figure 5). Pre-NFSA, beneficiaries stated that they had faced the problem of long waiting times at FPS (56%), no electronic weighing machines (EWM) (30%), inferior grain quality (20%), and delayed opening of FPS (20%).

Figure 5. Problems faced by ration cardholders pre- and post-NFSA (%)

The NFSA introduced reforms in coverage, entitlement rules, doorstep delivery of grains (in special cases), fixed distribution schedules, use of electronic point of sale (ePOS) and EWM, linking of Aadhar7 card to ration cards, and setting up a GRS. Post-NFSA, we do find a decline in some of the afflictions (Figure 5). Yet, the problem of long waiting times (56%) continues. Moreover, even post-NFSA, 18% found the quantity inadequate (quality-adjusted). Other issues like irregular disbursement, forced timing of disbursement, and delay in opening of FPS, continued even post-NFSA.

Digitalisation and service delivery

An e-POS machine generates a bill only if the corresponding weight, as per the entitlement, is placed on the EWM (Puri 2017), and hence helps protect entitlements. In our sample, 66% respondents report dealer using EWMs (Figure 6). Overall, there has been a significant improvement in the use of EWMs post-NFSA. In Odisha, 17% of the respondents report that EWMs are not being used. Though most beneficiaries find e-POS machines installed at FPS, 45% in EUP report technical glitches, erratic functioning, problems in biometric identification, and server (internet) issues, compared to 15% in Bihar and 9% in Odisha. Owing to these technical glitches, many respondents report spending more time at FPS, including revisits being required.

Figure 6. Use of electronic weighing machines (%)

Post-NFSA, some states introduced a system of sending text messages to beneficiaries to inform them about the availability and expected time of arrival of their foodgrain entitlements at FPS. However, our survey indicates a very small percentage (3% in Bihar, 1% in Odisha and EUP, respectively) receive these messages, as mandated under the NFSA. Majority (66%) get information straight from the dealer by visiting FPS, and 50% receive this information from their network of friends or neighbours.

Local corrective institutions: Grievance redressal systems

Chapter VII of the NFSA deals with GRS, which includes call centres, helplines, and designation of nodal officers for grievance redressal. Other provisions include a state government-appointed officer in each district (called District Grievance Redressal Officer or DGRO), and a state government-constituted State Food Commission (SFC) for monitoring and review of NFSA implementation.

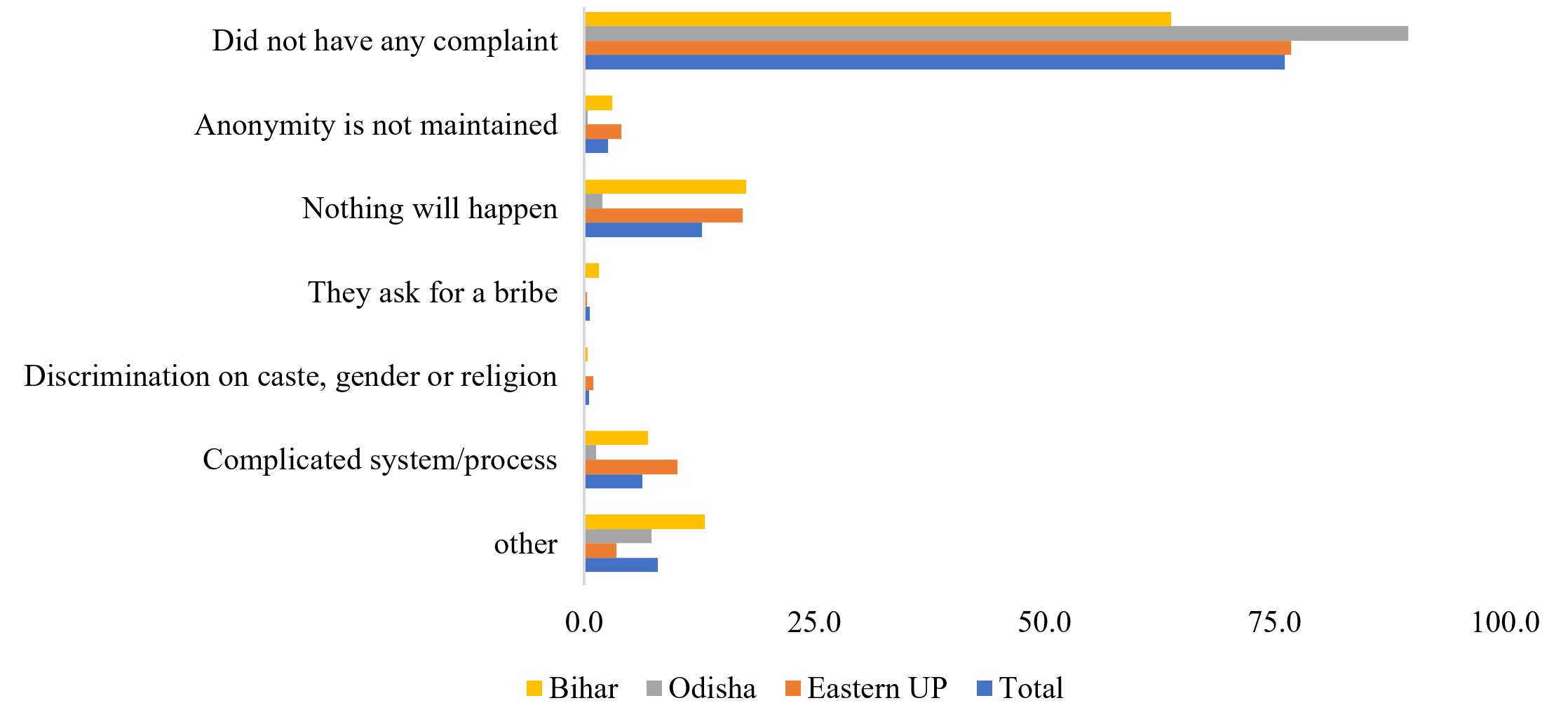

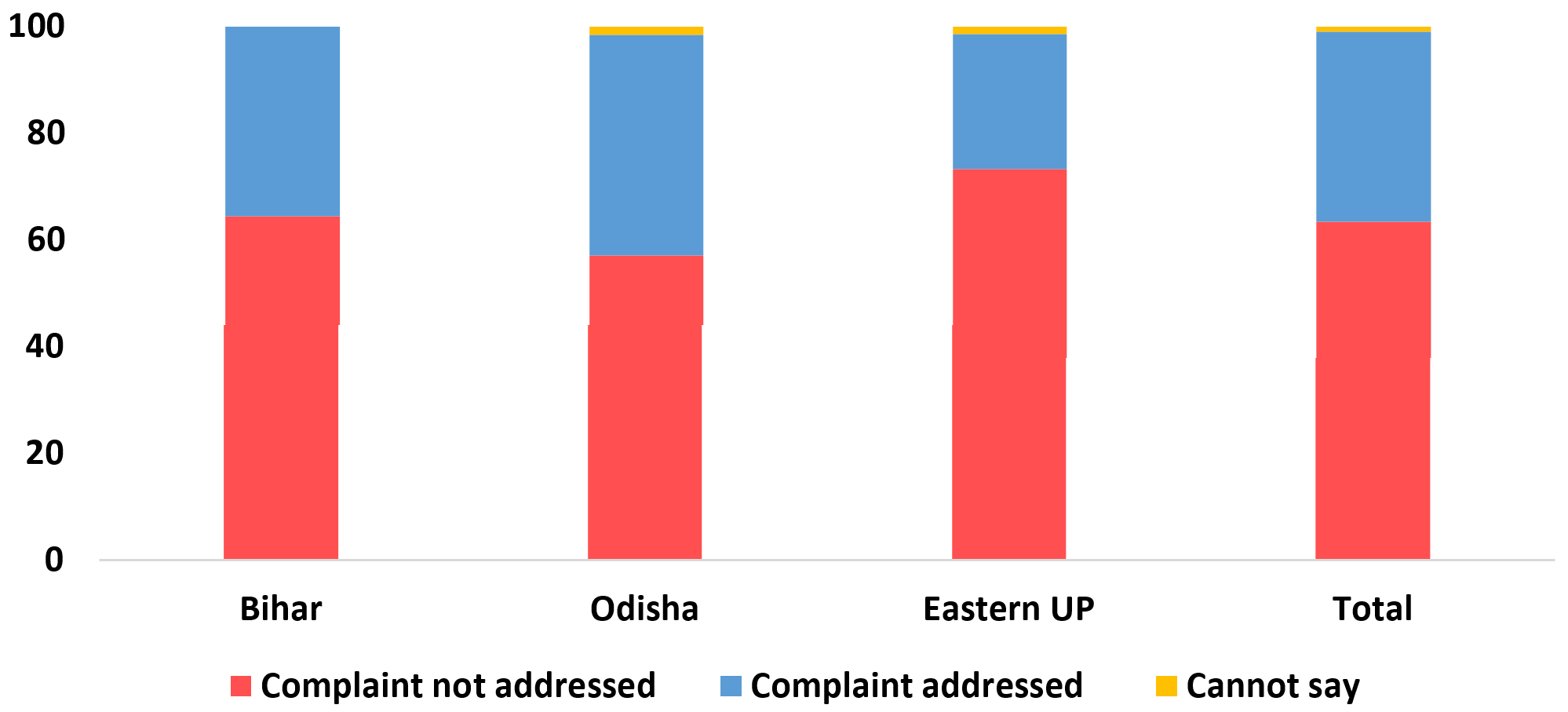

Seventeen per cent of the respondents in Bihar and EUP say that they do not have any faith in GRS, and 10% in EUP found the process too cumbersome (Figure 7a). Of the ones who filed a complaint, 64% in Bihar, 57% in Odisha, and 73% in EUP did not have their grievance addressed (Figure 7b).

Figure 7a. Reasons for not utilising GRS (%)

Figure 7b. Status of complaint (%)

The reasons reported for not using the GRS were identical in pre-NFSA surveys. Without collective action in using GRS, there remains a fear of coming under the spotlight as a troublemaker (Pradhan 2018). As noted by Majumder (2009) and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (2015), most beneficiaries do not complain or enter conflict because of the nexus between dealers and influential people, and also the deeply entrenched collusion between dealers, village council, and district-level supply officers.

One Nation One Ration Card: A subjective valuation

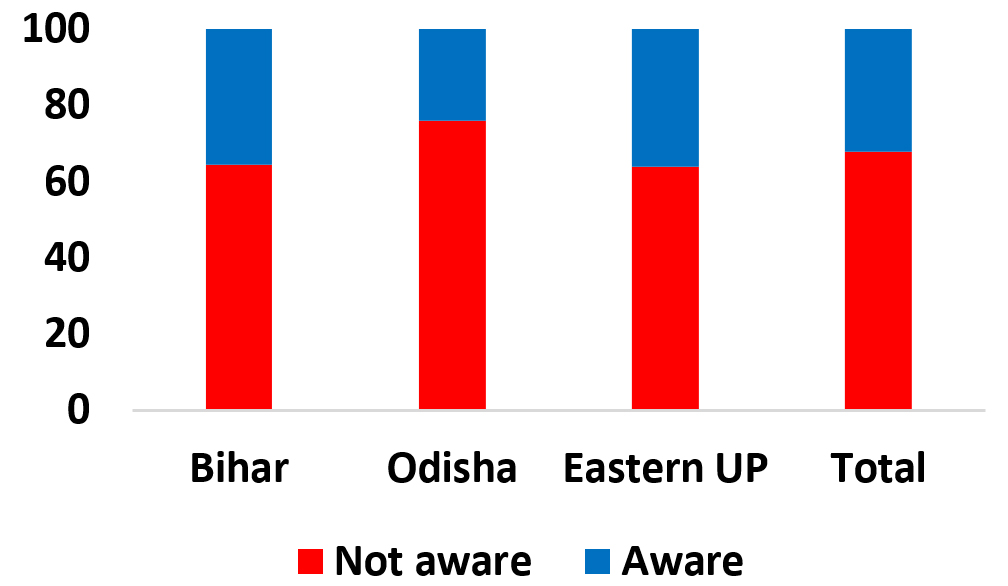

In June 2019, the central government introduced ONORC, which was given a go-ahead to be implemented nationwide by the Supreme Court only in July 2021. Since June 2021, Bihar and UP have adopted an integrated management of PDS, providing a technological platform for the intra-state portability of ration cards. We assess the awareness and valuation of ONORC, its effectiveness in delivering portability as well as divisibility in allocation. Most of our respondents (57% in Bihar, 62% in EUP, and 72% in Odisha) are neither aware, nor understand ONORC (Figure 8a).

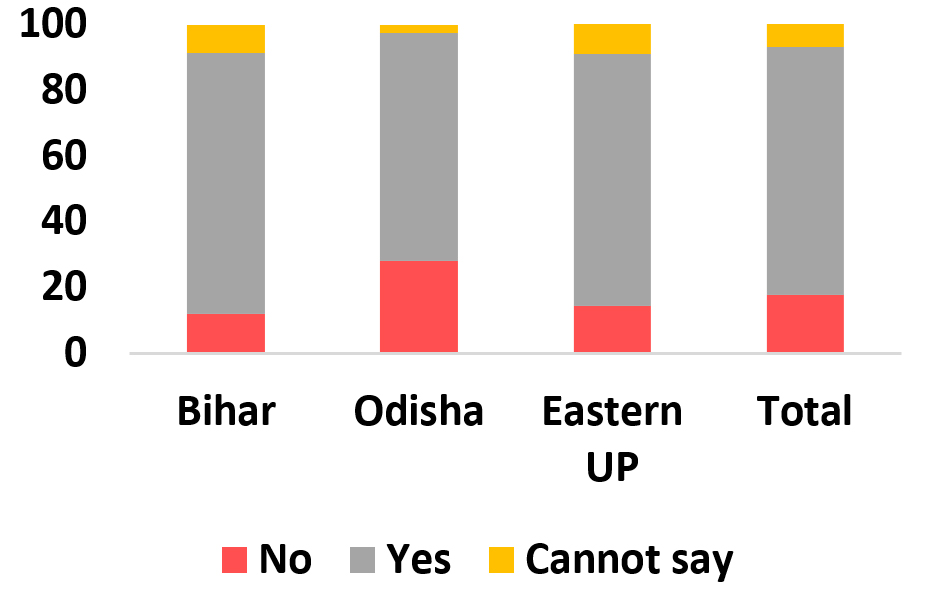

Yet, upon explaining, 76% were willing to pay for ONORC (Figure 8b). Bihar, a source of several migrant workers, has the majority of survey respondents (80%) willing to pay for ONORC.

Figure 8a. Awareness about ONORC (%)

Figure 8b, Willingness to pay to avail ONORC

PDS during Covid-19

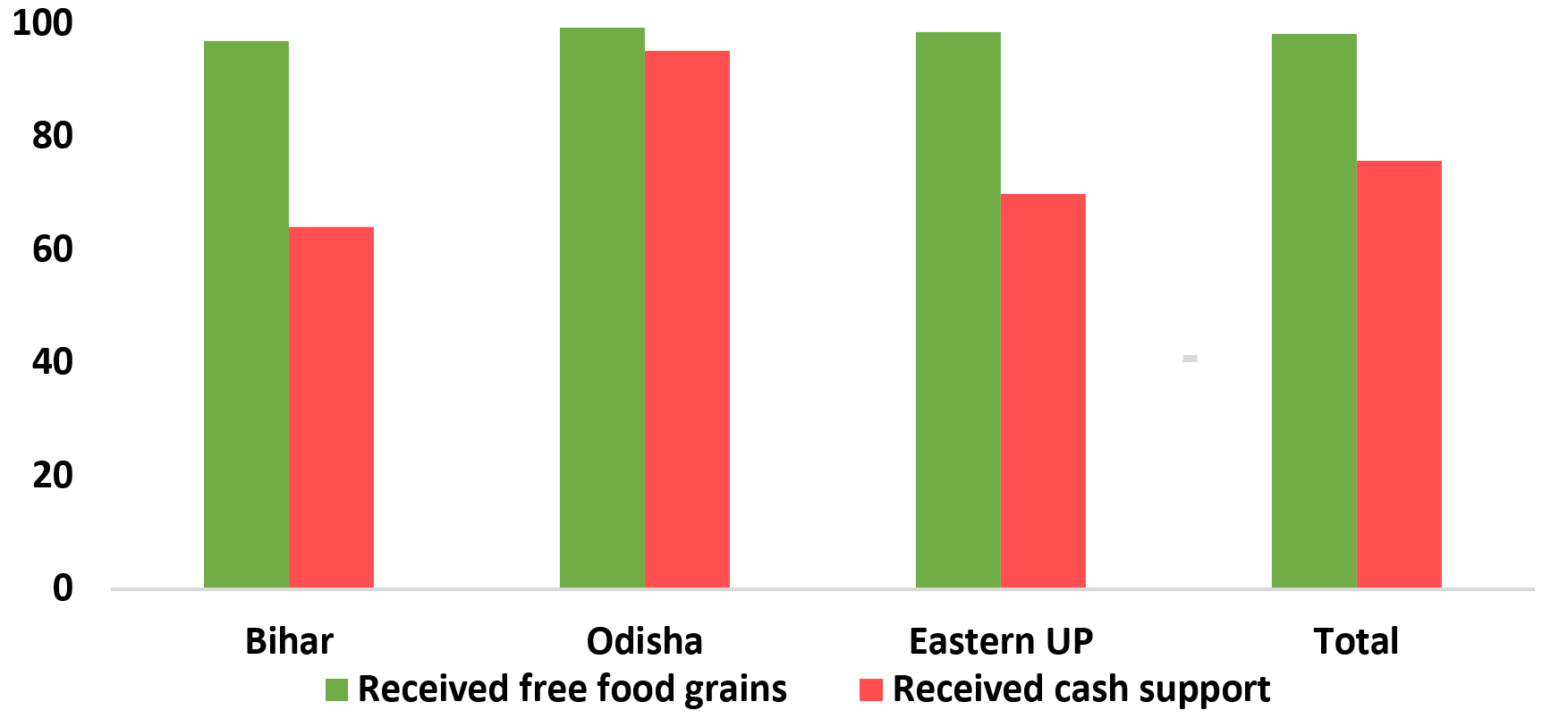

In March 2020, the government announced free foodgrains and cash payments to women, senior citizens, and farmers as part of the PMGKY. Our survey shows that an overwhelming 98% (Figure 9) did receive free foodgrains, that is, 5 kg rice or wheat and 1 kg pulses. However, in numerous cases, household members had been left unaccounted in the PDS food relief, which is important when there is per capita allotment (Roy et al. 2020). The government was also unable to honour the ‘pulse of choice’ pledge because of supply constraints. All households got either chana (chickpeas) or chana daal (split chickpeas). The 1 kg allocation of pulses is found to be inadequate, with a more accurate estimate of requirement being 4-5 kg.

Figure 9. Government support during Covid-19 pandemic

Conclusion

Focusing on EUP, Bihar, and Odisha, we study PDS in the post-NFSA scenario. There is evidence of some positive movements like coverage of households, but there is considerable scope for improvement in other areas. There are areas beyond prices and quantities of grains that need to be addressed, such as the quality, variety of grains, and quality of services at FPS, that result in differential access even post-NFSA.

Policies must consider different ways in which beneficiaries do not get their due even after the NFSA. Our results show that the promised GRS, as part of NFSA, is hardly effective. With or without the NFSA, policies need to internalise the multitude of factors that interact in complex ways to determine access. Other experiments on policies like EPOS machines, EWMs, and the link with biometric identification seem to be find mixed results.

We reckon that these differential experiences with PDS are not accidental and are likely a result of poor design, and a lack of sensitivity to the demand side of the programmes in keeping with community needs and preferences.

During Covid-19, PDS seems to have delivered but issues with eligibility and lack of commodity choices remain even with the NFSA. Finally, in terms of some due refinements like ONORC, again we find a need for greater information dissemination and extension of portability to include divisibility. Contingent on understanding how ONORC works, there is willingness to pay for it in regions with large migrant populations.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Antyodaya Anna Yojana is a targetted government scheme, which aims to provide highly subsidised foodgrains to the poorest BPL households.

- Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a Rs. 2.7 trillion relief package under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana for the poor during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Due to Covid-19 induced lockdowns, and social distancing rules in place, we conducted the survey over the phone between December 2020 and February 2021.

- The One Nation One Ration Card scheme allows eligible beneficiaries to avail foodgrains they are entitled to from any fair price shop across the country.

- Quantitative results from an earlier survey (Pradhan 2018) that we conducted identifies pathways through which group disadvantage emerges in the PDS. A consistent source of discrimination was in terms of quality where poor quality grains – in terms of bad odour, bad taste, bad colour, presence of stones, other elements, and insects – were mixed. Across the three states, the major complaint among most rights-holders was that the dealer blends the good and bad quality rice together. This is despite their requests to give it separately. With poor quality grains, women have to work more to sort and clean. Poor quality of the grains forced the supplementing of PDS grains from markets. The problems of quality were more pronounced for disadvantaged groups in terms of caste, gender, and class.

- This figure was nearly the same in pre NFSA period.

- Aadhaar or Unique Identification (UID) number is a 12-digit identification number linked to an individual’s biometrics (fingerprints, iris, and photographs), issued to Indian residents by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) on behalf of the Government of India.

Further Reading

- Bezbaruah, MP (2013), “Food Security: Issues and Policy Options; A Discussion in Light of India’s National Food Security Act”, Space and Culture, India, 1(2): 3-11.

- Bhattacharya, S, V Falcao and R Puri (2017), ‘The Public Distribution System in India -Policy Evolution and Program Delivery Trends’, in H Alderman, U Gentilini and R Yemstov (eds.), The 1.5 Billion People Question: Food, Vouchers, or Cash Transfers.

- Choithani, C and B Pritchard (2015), ‘The significance of local power structures in Bihar's coupon-based PDS’, Ideas for India, 17 August.

- Dreze, Jean, Prankur Gupta, Reetika Khera and Isabel Pimenta (2019), “Casting the Net: India's Public Distribution System after the Food Security Act”, Economic and Political Weekly, 54(6).

- Majumder, B (2009), Political Economy of Public Distribution System in India, Concept Publishing Company.

- National Council of Applied Economic Research (2015), ‘Evaluation Study of Targeted Public Distribution System in Selected States’, Report.

- Pradhan, Mamata and Devesh Roy (2019), “Exploring the Markers of Differential Access to PDS”, Economic and Political Weekly, 54(26-27). Available here.

- Pradhan, M (2018), ‘Understanding the demand side of social protection programmes: the case of public distribution of food in India’, University of East Anglia.

- Puri, R (2017), ‘India's National Food Security Act (NFSA): Early Experiences’, LANSA Working Paper Series 14.Roy, D, R Boss and M Pradhan (2020), ‘How India's food-based safety net is responding to the COVID-19 lockdown’, in J Swinnen and J McDermott (eds.), COVID-19 and global food security.

16 August, 2021

16 August, 2021

By: Janardhana Reddy 16 August, 2021

Thank you For providing Such an informative article. This Article has Lot of Valuable information. Thank you. www.vividdiagnostics.in