In the third post of the e-Symposium on ‘Carrying forward the promise of International Year of Millets’, Ashwini Kulkarni considers how the increased focus on millets during this year is just the beginning. She reflects on existing efforts to promote millet consumption, and the need to plan for the decade ahead– by reforming the millets value chain, promoting lesser known millet varieties, providing incentives and support to small farmers during the production process, and increasing research and development into methods for improving productivity and processing of millets.

The United Nations has declared this year as the International Year of Millets (IYM). This is a welcome development, since it provides a long-awaited window of opportunity to stimulate millet production, trade and consumption in multiple ways. The significant policy attention that millet production has received this past year, and is expected to receive over the next few years, helps shift focus of conversations about the agriculture sector away from wheat and rice exclusively.

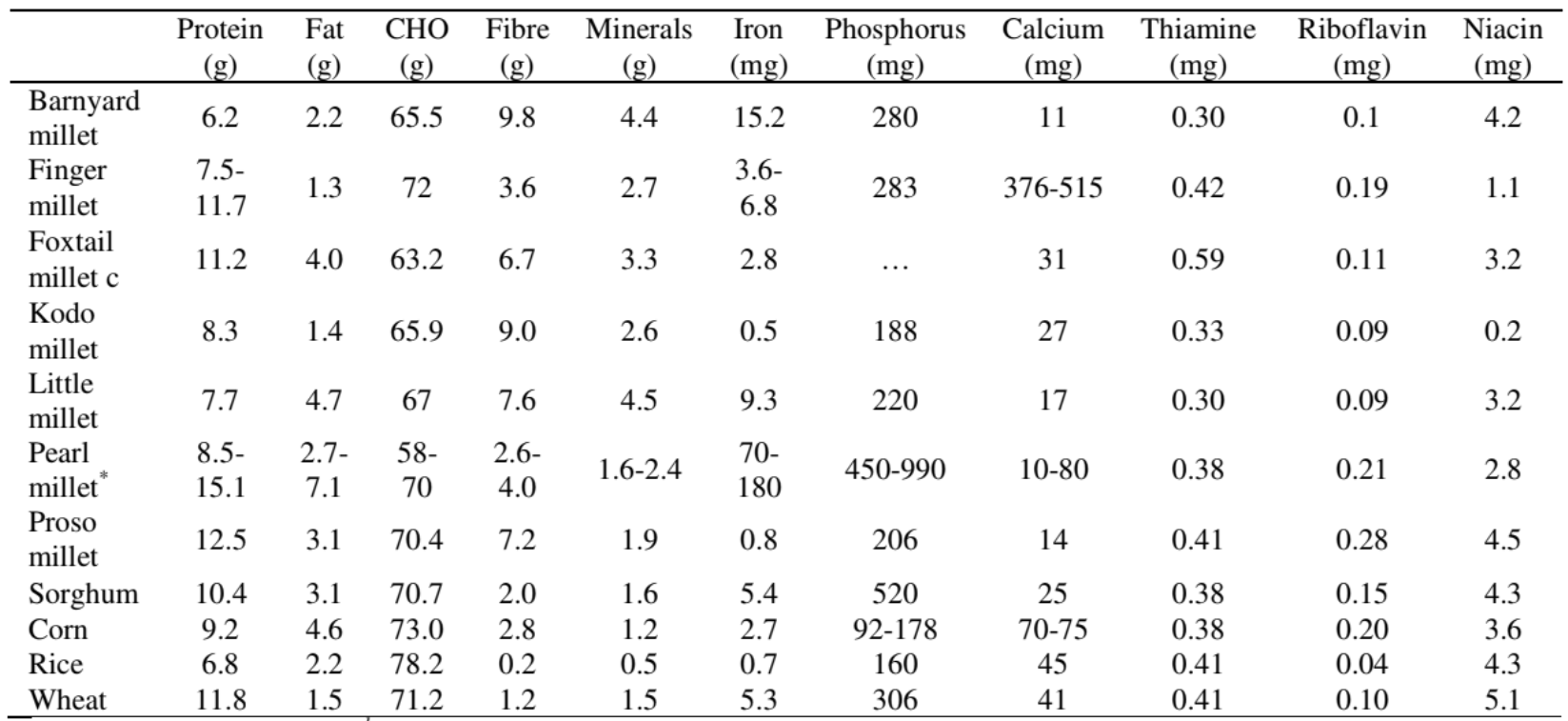

Millets have long been known for their nutritional value. The nutritional value provided by finger millet (ragi), pearl millet (bajra) and sorghum (jowar) is at par with wheat flour and substantially above that of rice (India Data Insights 2023). This is illustrated in Table 1 below. As India has been deemed the ‘diabetes capital’ of the world, increasing the intake of millets in daily meals can be among the basket of food options available to help regulate the incidence of a complex disease.

Table 1. Nutritional composition of various millets and cereals (per 100 g at 12% moisture content)

Conversations around millets also finally bring into prominence what many scientists and practitioners have known already – that millets are climate-resilient, and can become a flagship agricultural commodity for sustainable food systems’ transformation in the country. Millet production is part of India’s rich ecological and cultural heritage as well, and has historically been the primary grain of choice for a large section of India’s population living in the arid and semi-arid parts of the country.

Efforts to promote millet consumption

On 10 April 2018, the Government of India issued a notification which termed the minor millets, popularly known as coarse cereals, as ‘nutri-cereals’, and recently, it has also been named ‘Shree Anna’. In the 2023 Budget, the National Institute of Millets Research was recognised as a Centre of Excellence and given a higher outlay for its research and capacity building work. The union government as well as several state governments have been organising various programmes celebrating and acknowledging the importance of millets. It is very heartwarming to see a traditional crop, grown mostly by subsistence farmers, getting its due attention. These programmes highlight the nutritional value of millets, and since most of them are aimed at urban consumption, with new recipes and new products to make millets more attractive, the demand is likely to increase. Apart from sorghum and pearl millet, other lesser-known millets are also being increasingly showcased, which could be the first step towards a sustained and varied increase in demand.

Now that there is sufficient attention being given to millets, there is a need to start planning for the next decade. One year of commemorating the crop should be the starting point for policy planning to ensure it translates into a decade of positive movements on the production and consumption front. For millet production and consumption to increase and become attractive to all types of consumers not only as a supplementary health product but also as their choice of staple grain, it is crucial to work on ensuring back-end extension services are available to millet producers. This should include efforts to reform the entire millet value chain – from production to processing – so that it becomes accessible enough to be a part of the lifestyle of more Indians.

The need to support millet varieties

Millets have traditionally been grown in specific agro-climatic regions in states like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. Millet production in these states is predominantly led by rain-fed small landholding farmers. While sorghum and pearl millets are grown in larger quantities for sale, which then find their way to local kirana stores in nearby cities, there are several varieties1 which are relatively unknown and grown mostly for home consumption. Production of these varieties has little or no marketable surplus. These smallholder farmers have evolved and maintained these crops for decades and continue to cultivate them, in this way preserving the ecological heritage of their region.

For decades, Civil Society Organisations have been working with farmers to revive and popularise some millet varieties. Efforts to revive them using a new package of practices has shown encouraging results already. This is the experience that my organisation Pragati Abhiyan has gatherered while working with more than 2,000 farmer families across three districts in Maharashtra – Nashik, Palghar and Thane.

We introduced some changes in cultivation practices to them – for instance, instead of burning dry leaves on the farm plot, we set up nursery beds. While transplanting saplings, we encouraged them to use line sowing, with adequate spacing and Jeevamrut, an organic fertiliser prepared at home. Since farmers use seeds selected from their own plot, we provided them with seed treatment, as well as information about pests and fungal attacks, identification of diseases, and using neem and other homemade solutions to tackle them. We also introduced cycle weeders to reduce the drudgery of women while weeding.

From these efforts, we also discovered that millets are quite sturdy, do not require much water, can withstand dry spells during monsoon, can grow in shallow soils and are quite resistant to weather variability. Hence, they are climate resilient, providing farmers with reasonable yields even in times of extreme weather events.

Though they are gaining importance now, these crops have been neglected by government policies in terms of support for research and development, as well as any subsidies or procurement. Since these crops are predominantly cultivated by rainfed farmers, they do not need to avail large water and electricity related subsidies anduse very few inorganic fertilisers or chemicals for disease management, making them resource efficient.

Suggestions for good production practices of millets

For productivity of millet cultivation to increase, organic fertilisers and integrated pest management practices need to be provided to farmers who are already growing these crops. Farmers who have been cultivating these crops have also maintained the germplasm and its diversity, and so can work to developing varieties and landraces2 and participate in field trials.

Farmers would also need to be given incentives to increase area under cultivation. Such incentives can take several forms. For instance, a sustainable package of practices needs to be institutionalised so that farmers are supported through the production process.

Value addition is key: there is a dearth of appropriate machinery for the primary processing of millets like threshing, grading, and sorting machines, and pulverising machines made exclusively for minor millets. Small-scale machines need to be developed by agriculture universities for specific millets. The size of the machines is important to consider– if they are small and do not require three-phase electricity3, then they can be used by local enterprises to stimulate rural employment generation. On the other hand, big machines are likely to be capital intensive and would then be located in urban areas, which implies that small farmers have to bear transportation costs in order to access them.

Harnessing the momentum of IYM

Supporting the cultivation, processing and procurement of millets provides the opportunity to reach out to those farmers who have been left out of the benefits of the Green Revolution. It is a way to acknowledge and encourage farmers who have nurtured the ecological diversity of food grains. This can be an incentive to continue having a good crop mix which is climate resilient and reduces distress. It can also be an impetus to increase the marketable surplus of minor millets. A millets-specific policy can directly support the farmers who are at the bottom of the pyramid and provide nutrition to large sections of the population.

For a few millets (like finger millet, sorghum and pearl millets), Minimum Support Price (MSP) has been announced, but procurement remains low. As a start, governments can plan to procure locally grown millets for ICDS (Integrated Child Development Scheme), Anganwadis, Mid-day Meals, government residential schools, and such.

Such policies would require the cooperation of many Ministries – Agriculture, Rural Development, Tribal Development, Women and Child, Civil Supplies and such – as well as an intelligently managed convergence of various schemes and funds across departments. It also requires creative development of methods for increasing productivity, storage, primary processing and value addition. This is possible if this year is considered as the start to a ‘Decade of Millets’.

Notes:

- These varieties include finger millet, foxtail millet, proso millet, barnyard millet, kodo millet and little millet.

- Landraces are domesticated, locally adapted, traditional varieties of a species of plant that has developed over time, through adaptation to its natural and cultural environment of agriculture, and due to isolation from other populations of the species.

- Three-phase power systems provide three separate currents, each separated by one-third of the time it takes to complete a full cycle. With respect to its usage, single-phase power is used where electricity requirement is low and is used to run small equipment. The three-phase power can carry a heavy load to run large machinery.

Further Reading

- Deshpande, SS, D Mohapatra, MK Tripathi and RH Sadhvata (2015), "Kodo Millet-Nutritional Value and Utilization in Indian Foods", Journal of Grain Processing and Storage, 2(2): 16-23. Available here.

- India Data Insights (2023), ‘Millet cultivation in India: History and trends’, India Development Review, 24 March.

19 October, 2023

19 October, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.