It is widely believed that the extent of deforestation in developing countries is large and growing over time, and that this has significant adverse effects on local livelihoods. This column presents findings of a study of the mid-Himalayan region, and contends that forest degradation, not deforestation is the key problem. It discusses the determinants of degradation and what can be done to limit it.

Deforestation in developing countries is an urgent global problem, adversely affecting climate change, soil erosion, major river basins, and livelihoods of poor households living near forests. Public discussions on the problem are frequently dominated by widely held beliefs concerning the extent of deforestation (that it is large and growing over time), and its impacts on local livelihoods (that these are adverse and large). Factors such as economic growth, local poverty and inequality are generally believed to accelerate the process. Of possible remedies, the most widely discussed one involves property rights over forests - that local communities should be granted ownership and management autonomy in order to arrest deforestation.

There are many good reasons why these propositions could be true, informed both by economic theory and casual analysis of data. Human populations use forests for household energy, fodder for livestock, and timber for wood products. Forest areas are often cleared to expand agricultural cultivation, mining exploration, residential construction or land for urban use. Economic growth that increases demand for food, energy, mineral resources, furniture and housing could thus naturally increase deforestation. Among those living near forests, the poorest households rely on forests the most for firewood, fodder and other produce - they rely more on livestock grazing, are least able to afford commercial fuels or timber, and have numerous family members (especially women and children) with a low opportunity cost of time who can be sent to collect forest products. Hence, increased poverty among neighbouring populations could increase human pressure on the forests. Heightened deforestation could therefore have a severe impact on local poverty, possibly generating a vicious spiral as this increased poverty may in turn accelerate deforestation. Women and children, the principal collectors, are likely to be the most adversely impacted. Greater socio-economic inequality of local communities could undermine their capacity to engage in collective action to impose and enforce curbs on forest use. Shifting ownership rights over forests to local communities away from the State might therefore enhance the scope and power of such collective action.

These views are commonly expressed in numerous anecdotes, media reports, scholarly treatises, policy documents of national governments and international organisations. To what extent are these upheld by results of ground-level research and data analysis? Do they apply equally to different countries or continents?

In collaboration with various researchers over the past decade, we undertook a study of the mid-Himalayan region spanning Nepal and northern India, using a variety of detailed micro-level datasets (Baland et al. 2010). For Nepal we relied on three successive rounds of the nationally representative household Living Standards Measurement Survey (LSMS) (1995-2010). For the Indian states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand that falls in the same geo-climatic zone as Nepal, we carried out detailed household, community and forest surveys during 2001-2004. The findings turn out to be similar across Nepal and the two Indian states, as well as with studies in these regions by a number of other researchers.

Increasing deforestation?

There is no clear evidence that deforestation in this part of the world is accelerating over the past few decades. For India as a whole, Foster and Rosenzweig (2003) use aerial satellite data on forest biomass and find the opposite phenomenon of reforestation. Our detailed ground-level forest surveys in Himachal and Uttaranchal indicate that the key problem is degradation rather than deforestation. Tree branches are heavily lopped, stunting tree growth and limiting foliage. 61% of forest areas sampled exhibited crown cover below the ecologically sustainable threshold of 40%. In contrast, measures of tree biomass were not alarmingly low - average basal area1 exceeded the sustainability threshold of 40 square metres per hectare. While forest areas have receded owing to growing encroachments, this accounts for a relatively small fraction of the increased times taken by households to collect firewood. Over the past quarter century, firewood collection times have increased 60% on average, but walking time to the forest increased only 10%. The bulk of the increased collection time owed to declining quality of the forest, with households taking longer to find firewood owing to trees being more heavily lopped.

Determinants of forest degradation

We study the effects of the various determinants of forest degradation on household firewood and fodder use, and on the quality of neighboring forests.

Economic growth: The effect of economic growth on degradation depends on the precise way that growth is measured. If it is measured in terms of household consumption levels, the evidence (based on estimated household Engel curves2) shows that economic growth aggravates degradation - rising consumption levels (up to the 95th percentile3) are associated with increased firewood collection/ use. However, the same is not true when growth is measured in terms of key household productive assets rather than consumption levels. Only growth in livestock assets has a strong positive impact on firewood collection. The effect of land ownership is negligible, and education and non-farm assets have a negative effect. Indeed, in Nepal villages, per household collections of firewood fell between 1995 and 2010, explained mainly by rising education and non-farm assets, shrinking livestock and greater outmigration. Hence, the nature of growth matters. If it is accompanied by occupational changes wherein local populations shift from traditional livestock or land-based occupations to modern non-farm occupations, a reduction in forest degradation can occur. The opposite may happen if growth in living standards is driven by rising income transfers from the government or remittances, or by rising livestock assets.

Demographic factors, such as the rise in population and increasing fragmentation of rural households turned out to be far more important determinants of forest degradation in the Himalayas, as compared to economic growth. Shrinking household size, growing population and slow rates of permanent out-migration have translated into fast growth in the number of rural households, raising forest degradation. A 10% growth in productive assets in the two north Indian states was estimated to raise household firewood use by less than 0.2%, while a 10% growth in population was estimated to raise it by 9.9%.

Local poverty: There is no evidence that poor households collect more firewood than non-poor households. In reality, it is the other way around. Non-poor households have greater energy needs, related both to consumption of cooked foods, size of house and of heat during the winter. Declining poverty is therefore unlikely to arrest forest degradation4.

The data also shows very limited evidence for the reverse link between forest degradation and current living standards of neighbouring populations. An increase in firewood collection time by an hour in northern India (comparable to the collection time observed over the past quarter century) was estimated to lower household consumption by less than 1% uniformly across poor and non-poor households. The reason is that households accumulate firewood during lean agricultural seasons, when the opportunity cost of their time is low. It is possible, however, that there will be some adverse effects on local livelihoods in the long run, if current degradation trends continue.

Local inequality or collective action: Neither is there any evidence that increased inequality of consumption or land ownership in neighbouring villages is associated with greater pressure on adjoining forests. Informal collective action to regulate forest use in northern India is conspicuous by its absence, except in a few locations. This does not reflect a general inability to engage in collective action, as indicated by functioning informal cooperatives in the context of other local public goods, such as irrigation or temples. Part of the reason could be the fact cited above: a more degraded forest has a negligible impact on current household livelihoods. So local communities do not worry about the condition of neighbouring forests or try to regulate use of forest products.

Local community ownership and management: Both Nepal and India have transferred ownership and responsibility for management of forests to local communities, in the form of forest-user-groups (FUGs) in Nepal and Van Panchayats (VPs) in northern India. These local organisations have created and enforced rules for firewood and fodder use by their members, and engaged in reforestation programmes. Studies have found a 10-20% reduction in household firewood use in either region as a result of these changes5. In northern India these findings are corroborated by reduced lopping of forests transferred to VPs, compared with neighboring state and open access forests.

Costs of household energy substitutes: Our studies in northern India show that a household’s use of firewood is sensitive to the cost of alternate modern fuels, especially Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG). A subsidy of Rs. 100 ($2 approx., one-third the cost in the early 2000’s) on an LPG cylinder was estimated to reduce household firewood use by 20-27%.

Concluding remarks

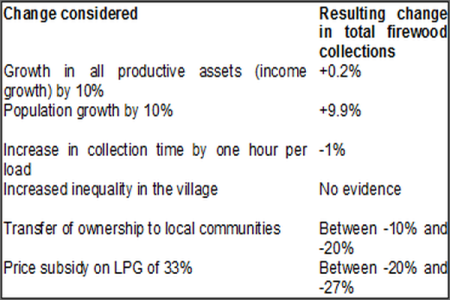

In summary, many commonly stated views - such as effects of economic growth, poverty reduction, or local inequality on forests, or of the reverse effects of forest degradation on local livelihoods - turn out either to be invalid, or require serious qualification, in the Himalayan context. Our main findings are summarised in the following table:

Table 1. Effects of various changes on firewood collections

What appears to be true instead is the following. Forest degradation is a serious problem, from the standpoint of its larger, non-local ecological and climate change impacts, as well as possible long-run impacts on local livelihoods. It results mainly from firewood and fodder use by households that live near the forests. Informal collective action by neighbouring local communities is unlikely to make a serious dent on the problem. Transfer of ownership and management to local communities is, however, likely to help moderate firewood use and encourage forest regeneration. Subsidies and increasing availability of modern energy substitutes will induce households to rely less on the forest. In the long-run, the most effective means of limiting degradation will be policies that control population growth, promote education, growth of non-farm occupations and permanent out-migration.

A version of this article has appeared in Poverty in Focus, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, United Nations Development Programme, and as a Policy Brief of the South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics (SANDEE).

Notes:

- Basal area is the term used in forest management to define the area of a given section of land that is occupied by the cross-section of tree trunks and stems at their base.

- An Engel Curve describes how household expenditure on a particular good or service varies with household income.

- A percentile is a measure used in statistics to indicate the value below which a given percentage of observations in a group of observations fall. For example, here, the 95th percentile is the value of consumption below which the consumption levels of 95% of the households fall.

- This result applies to both Nepal and northern India, and holds for different estimation methodologies.

- Estimating the impact of these changes raises a number of methodological problems – these are the results of the most careful studies available.

Further Reading

- J.M. Baland, P. Bardhan, S. Das and D. Mookherjee (2010), “Forests to the People: Decentralization and Forest Degradation in the Indian Himalayas”, World Development, 38(11), 1642-1656.

- J.M. Baland, S. Das and D. Mookherjee (2011), `Forest Degradation in the Himalayas: Determinants and Policy Options,’ in S. Barrett, K.G. Maler and E. Maskin (eds.), Environment and Development Economics: Essays in Honour of Sir Partha Dasgupta, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- J.M. Baland, P. Bardhan, S. Das, D. Mookherjee and R. Sarkar (2008) “Environmental Impact of Poverty: Evidence from Firewood Collection in Rural Nepal”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(1), 2010, 23-61.

- J.M. Baland, P. Bardhan, S. Das, D. Mookherjee and R. Sarkar (2007), `Managing the Environmental Consequences of Growth: Deforestation in the Himalayas’, in Suman Bery, Barry Bosworth and Arvind Panagariya (eds.), India Policy Forum 2007, Sage Publications.

- J.M. Baland, F. Libois and D. Mookherjee (2012), ’Firewood Collections and Economic Growth in Rural Nepal 1995-2010: Evidence from a Household Panel’, Working Paper no. 247, Institute for Economic Development, Boston University.

- A Foster and M. Rosenzweig (2003), “Economic Growth and the Rise of Forests”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118: 601-637.

- E. Somanathan, Prabhakar, R. and Mehta, B.S. (2009), ‘Decentralization for cost-effective conservation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 106(11), pp. 4143-4147.

10 March, 2014

10 March, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.