This year’s Economic Survey, the flagship document of the Ministry of Finance, was recently tabled in the Parliament at a time of economic slowdown and rural distress in India. In this post, Sudha Narayanan offers a critical review of the Economic Survey from the point of view of agriculture, while also proposing an alternative way of framing the issues mentioned in the report.

This year’s Economic Survey on the current state of the economy was recently tabled in the Parliament. As has been the case of late, the Survey is of two parts, the first offers the Chief Economic Adviser’s take on contemporary issues that define the times; the second report is a more traditional narrative account of the economic developments of the year. Both volumes tend to offer a mix of diagnosis and prescription, each chapter outlining a vision for the sector it addresses. This piece offers a critical review of the Economic Survey from the point of view of agriculture.

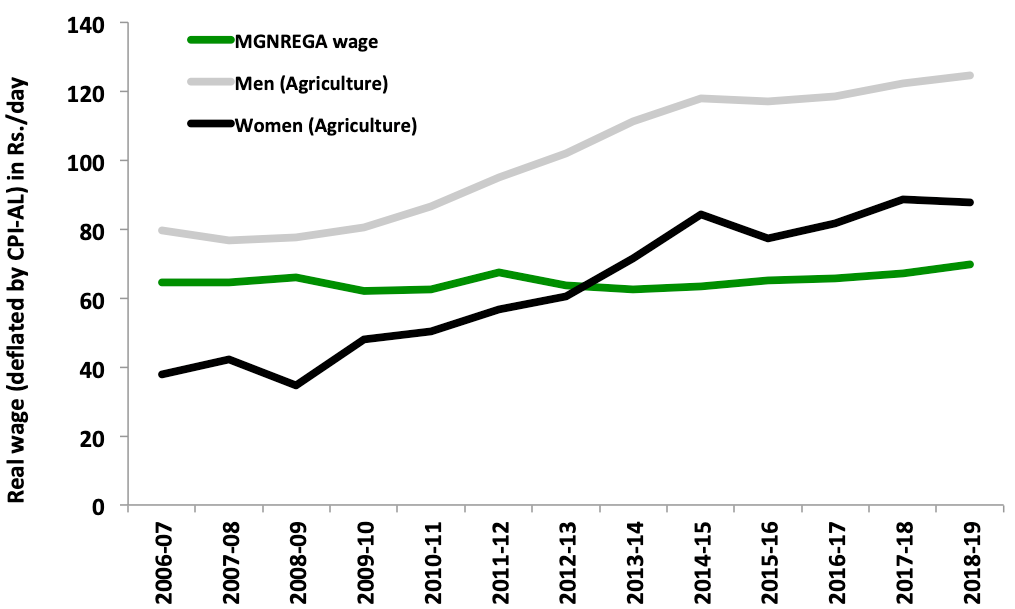

The last time the Survey had a chapter dedicated to agriculture was in 2017-18 – on ‘Climate, Climate Change and Agriculture’. Since then, growth rates in agriculture have fallen even more (from 5% in 2017-18 to 2.8% in 2019-20); these declines are greater than for the economy as a whole (which fell from 6.9% to 4.9% in the same period). Agricultural wage rates that had already decelerated by 2017-18 show few signs of recovery (Figure 1). Wages in construction are reported to have declined over some of this period. Programmes such as the MNREGA1 that cushion the impact of climatic and macroeconomic shocks for small farmers and landless workers offer neither reasonable nor timely wages. Given that 32% of agricultural household incomes come from wages (National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), 2013) agricultural households, especially the small and marginal farmers (with landholdings less than two hectares) do not seem to be doing well. For the consumer, which includes farm households as well, 2019 will perhaps be remembered as the ‘Year of the Onion’, with prices soaring, reminiscent of the 2010 and 1997-98 crises, without commensurate returns to the farmer. Embedded in these trends is a short-term economic emergency, but that also reflects longer-term challenges, in that some of these are consequences of deeper structural issues in Indian agriculture.

Figure 1. Real wages in agriculture and the MNREGA

Note: Agricultural wages are financial year average for ploughing and tilling; MNREGA wage refers to average wage paid.

Source: Author’s construction using MNREGA wage, all India official agricultural wage, and Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Workers.

Given widespread recognition that rural distress has been at the heart of the economic slowdown, it would have been entirely appropriate to devote a chapter to rural distress, with ways to address a short-term emergency while staying the course of long-term reform. Tackling this trade-off is not easy when resources are limited. It would have been timely too to reflect on the much publicised goal of doubling farmers’ income by 2022; while the 2022 is just around the corner, the target itself could not seem farther away.2 In the following section, I offer a selective summary of the salient issues relating to agriculture. I then conclude by proposing an alternative way of framing issues mentioned in the report in ways that might have been more instructive.

What does the Survey say about agriculture?

Although a dedicated chapter for rural and agrarian issues is absent, Volume I, Chapter 4 titled, ‘Undermining Markets: When Government Intervention Hurts More than it Helps’, refers to at least three major policies pertaining to agriculture. The first is the Essential Commodities Act, 19553 (ECA); the second pertains to foodgrain stocking policy, that is, procurement undertaken by the Food Corporation of India (FCI), in particular; and the third are debt waiver schemes as a whole. All three policies indeed require reconsideration, in part because, as the report argues, they have each had undesirable unintended consequences, possibly at a high cost. The report characterises these policies as unambiguosly “needless” that deserve to go. These prescriptions are however based on a patchy diagnosis and the analysis offered as justification is notably unencumbered by nuance.

Across the world there is agreement that in the context of agricultural markets, especially in developing countries such as India, we need new forms of regulation or intervention that would replace anachronistic ones – rather than an absence of regulation – since the structure of spot markets is rarely competitive. This possibility is not entertained at all in this chapter.

While the arbitrary use of ECA has been flagged as a problem for decades and many committees have recommended its removal, its removal will neither solve the problem of volatility nor of the wholesale-retail market spread. Indeed, evidence of the ineffectiveness of the ECA does not suggest that we need no regulation – but that that we need more effective and transparent regulation in agricultural markets. For example, one prescription has been that government intervention (through purchase and sale of commodities) in commodity markets can be linked to transparent price bands or thresholds; the ECA could therefore be used more effectively and transparently (Chand Committee Report, 2018).

In the same chapter, the report offers a contrast between gram dal (a legume) and rice to show how the ECA is ineffective in reducing both volatility and the wholesale-retail price wedge (Figure 8a and 9a, Volume I). Whereas rice price, which did not attract ECA action in that period remains stable, gram dal does not, despite ECA action. A few pages later, however, the report criticises rice procurement policies for thwarting competition. Ironically, the report does not recognise that the stability in rice prices portrayed in Figures 8a and 9a is primarily due to heavy market intervention, even if in the process government procurement crowds out competition. These examples, based as they are on comparisons such as these, confuse rather than clarify.

The question is simply not about doing away with current forms of regulation or intervention, but to be able to identify what form of regulation works best to achieve what objective, and the optimal level of regulation that we need. To deem many of these as “needless” and as undermining competition is to presume that these markets are competitive to start with, or would be in their absence – a deeply flawed assumption with agricultural markets in India. As for procurement, given that much of the procurement costs are in fact transfers to farmers (averaging around 60% over 2010-17), dismantling of procurement might be associated with costs of its own if farmers are not compensated in other ways. The analysis seems to neglect the trade-offs of removing these policies.

On debt waiver, the report suggests that it is unambiguously harmful to provide full waivers, and that it is challenging and costly to identify those who are truly distressed. While it is indeed valid that debt waivers should not be used routinely, suggesting that it has no place even in the short term as a palliative, seems to be ill-founded4.

The Survey’s Volume II offers a more cautionary approach to policy reform in its customary chapter on ‘Agriculture and Food Management’. It also covers a broader range of issues. Three things stand out as contrasts to recent editions of the Economic Survey.

First, it is bereft of the exuberance of earlier years when discussing the strategy of doubling farmers’ incomes, and schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bhima Yojana (PMFBY). Instead, we have a staid account that covers many issues – the need for support to mechanisation, micro-irrigation, income support, procurement programmes, insurance, storage, food processing, dairy and fisheries, and agricultural research.

Second, unlike previous report, it does not articulate a strong, coherent vision for agriculture, except in the concluding section – that outlines how farmer incomes might be doubled and highlights policies that are relevant for smallholder-dominated agriculture. Yet, the concluding vision does not tie in particularly well with the rest of the chapter. The Survey (Volume II) also does not seem unduly worried about dipping growth rates in agriculture, suggesting instead that this is consistent with structural transformation. This is perhaps more worrying than the declining growth rates itself since it suggests a vision of agriculture that seems inconsistent with rural realities, wherein land and farming are the fallback option for many, given that many do not find jobs in other non-farm sectors.

A third and especially disconcerting issue is the absence of continuity from previous years. Several promising and not so promising schemes with substantial allocations that were discussed in recent editions of the Economic Survey find no place in this one. For example, discussions on Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM), Zero-Budget National Farming (ZBNF) find no place in the recent Survey. Similar omissions include the Draft Seeds Bill of 2019 and the ‘One Million Farm Ponds’ programme from 2017-18. Some of these, such as FPOs and e-NAM are important in shaping the institutional context in which smallholders operate. Has the government perhaps dropped these as focal points for reform? It is hard to tell.

One gets the feeling that, instead of acknowledging what this year means for long-term agricultural reform, the Survey has taken refuge in showcasing numbers for programmes that involve some form of transfers to farmers. These are presented as achievements without reflecting on the implementational challenges. For example, there is useful, if limited, acknowledgement of the challenges associated with the PMFBY , but virtually none of those associated with PM-KISAN (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi), PMKSY (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana), and direct benefit transfers (DBT) for fertilisers. Each of these programmes have faced significant impediments in implementation. Serious discussions of the successes and failures of past initiatives are is crucial to our understanding of the path we can reliably take to reform the agricultural sector.

Agriculture today is a complex mosaic of actors, including those involved in organic and alternative agriculture, farmers’ organisations seeking to revive millets, and private-sector, technologically-driven agricultural start-ups in the finance, extension, and marketing space. This is the right time to reflect on the consequences and prospects of these actors in the agricultural ecosystem. Another notable ‘slide back’ is the silence on the predicament of women farmers – a concern that found place in earlier Surveys.

Reframing the discussion: what the Economic Survey could have done

Indian agriculture, with all its diversity and plurality, is at a turning point. There are difficult trade-offs between short-term exigencies and long-term structural reform. The need of the hour is to seek ways to address the short-term distress via palliatives, without foregoing the long-term vision for agricultural reform.

There are two immediate challenges associated with the latter. The first is to outline the choices between forms of regulation that would best work for Indian agriculture in the long run and assess our preparedness in terms of institutions and technological capacity, along with a roadmap to get there. This would require balancing the interests of producers and consumers. The second is choosing between forms of support. There is great merit in moving away from input subsidies and price-based support that have had harmful environmental and distributional consequences to more transparent income support. Yet, the design and delivery mechanism of these remain challenging, especially because these policies would need to reach tenant and women farmers, who will increasingly be the farmers of the future. We already know that the identification of farmers, of clear land records, and the chaos associated with the linking of Aadhaar in direct payments schemes all pose huge challenges.

Much of the innovation in the design of farmer support has come from the states, with some from the Centre, and each has its own design, target group, and modality of transfer. Examples include Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana (BBY), a price deficiency payments system in Madhya Pradesh; DBT for fertilisers; the Krushak Assistance for Livelihood and Income Augmentation (KALIA) in Odisha; the Rythu Bandhu in Telangana; the PM-KISAN and PMFBY across India; and the Bihar Rajya Fasal Sahayta Yojana (BRFSY). There is much to learn from these diverse models as we shape the nature of support that works best for farmers. The Economic Survey would have been the ideal place for such a discussion.

In short, the Economic Survey 2019-20 missed an opportunity to clearly outline a path for long-term reform – forms of regulation and support that might work best for Indian agriculture – while clarifying the urgency of short-term measures to tide over the current crisis. In doing so, it gives the impression that the Survey lacks a clear, forward-looking policy strategy with respect to agriculture.

Notes:

- MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at state-level statutory minimum wages.

- The Dalwai Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Incomes (2016) had pointed out that to achieve the target, real incomes of farmers would have to grow at a compound annual rate of 10.4%. It is only belatedly that it has been clarified that target of doubling farmers’ incomes refers to doubling it in nominal terms. Rajiv Kumar, Vice-Chairman, NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog, deemed it “doable“ in an interview on NDTV with Prannoy Roy, on 1 February 2020.

- The essential Commodities Act, 1955 was enacted to regulate production and distribution of certain commodities considered to be ‘essential’ for consumption, in order to protect consumer interests and to make them available to consumers at fair prices.

- See Narayanan and Mehrotra (2019), for a review of these arguments and studies that emphasise a role for such debt waivers and Sen (2017).

Further Reading

- Government of India (2020), ‘Economic Survey 2019-20’, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, New Delhi, January 2020.

- Narayanan, Sudha and Nirupam Mehrotra (2019), ‘Loan Waivers and Bank Credit: Reflections on the Evidence and the Way Forward’, Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 44(4): 198-210.

- National Sample Survey Office (2014), ‘Key Indicators of Situation of Agricultural Households in India: NSS 70th Round (January-December 2013)’, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- Sen, P (2017), ‘Are farm loan waivers really so bad?’, Ideas for India, 23 June 2017.aivers and Sen (2017).

05 February, 2020

05 February, 2020

By: Udit 16 February, 2021

Economic survey valid idea 19-20