Children in India are among the shortest in the world. This article uses the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) data to examine the complexity and diversity of child height in the country. It finds that India's overall average child height-for-age improved between 2005-06 and 2015-16. Although important, this increase is small relative to India’s overall height deficit and its economic progress.

The average height of a population’s children is an important measure of human development. The distribution of height, in a population, reflects the health and well-being that children experience at young ages. What happens to babies and children matters for their achievement, health, and survival throughout their lives.

For decades, policymakers, researchers, and everyone concerned with child well-being have agreed on one simple fact: India's children are among the shortest in the world. Unfortunately, for the last decade or so, we have relied on one core source for this fact: the 2005-06 round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3). The NFHS is India's version of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

To be sure, other available data sources – such as the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), the HUNGaMA1 survey, and localised datasets – agreed with this basic fact. But for detailed analysis of the complexity and diversity of the height of Indian children, there is no substitute for a DHS. Years went by without new data, even as Bangladesh, Nepal, and other countries all released many DHSs. A researcher could be forgiven for wondering whether some decision-makers were indifferent to the facts about child height.

In 2015 and 2016 that changed. From January 2015 to November 2016, a new DHS was collected: India's NFHS-4. Surveyors throughout India measured a representative sample of 180,867 children below five years of age. These data were released online in January 2018. The interest from the research community was immediate: our friends and collaborators began emailing us the very morning that the data file appeared online. With rapid economic growth and other improvements in human development, health, and nutrition, researchers expected that the average child would be taller than a decade ago. But by how much? Is India catching up to the rest of the world? And who, within India, is gaining the most? For the first time in a long time, there is new data to provide answers.

What is different?

In recent research (Coffey and Spears 2018), we analysed the NFHS-4 child height data. Statistical researchers summarise child height in ‘height-for-age standard deviations2’. Height-for-age quantifies how different a population of children is, on average, from the distribution of heights among healthy children. An average height-for-age of ‘0’ would indicate a healthy population; unfortunately, numbers for sub-populations of Indian children are generally negative.

From the 2005-06 survey to the 2015-16 survey, India's overall average child height-for-age improved from -1.87 to -1.48. That is a large and important improvement. Average height improved among rural children and urban children, boys and girls, in the northern plains states and in the rest of India. These increases represent important advancements in human development.

One way to look at the statistics is that the places that are most disadvantaged within India are now about as badly-off as all of India was 10 years ago. So, in 2005-06, the average Indian 3-, 4-, or 5-year-old (living anywhere in India) had a height-for-age of -2.11. This is short enough to classify as ‘stunted’, a condition which indicates an extreme level of deprivation. Now, in 2015-16, the average rural child of these ages in Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, or Uttar Pradesh has a height-for-age of -2.06. So, the places that need the greatest policy focus are now approximately where all India was 10 years before. There has been clear progress, but there remains stable inequality.

What is the same?

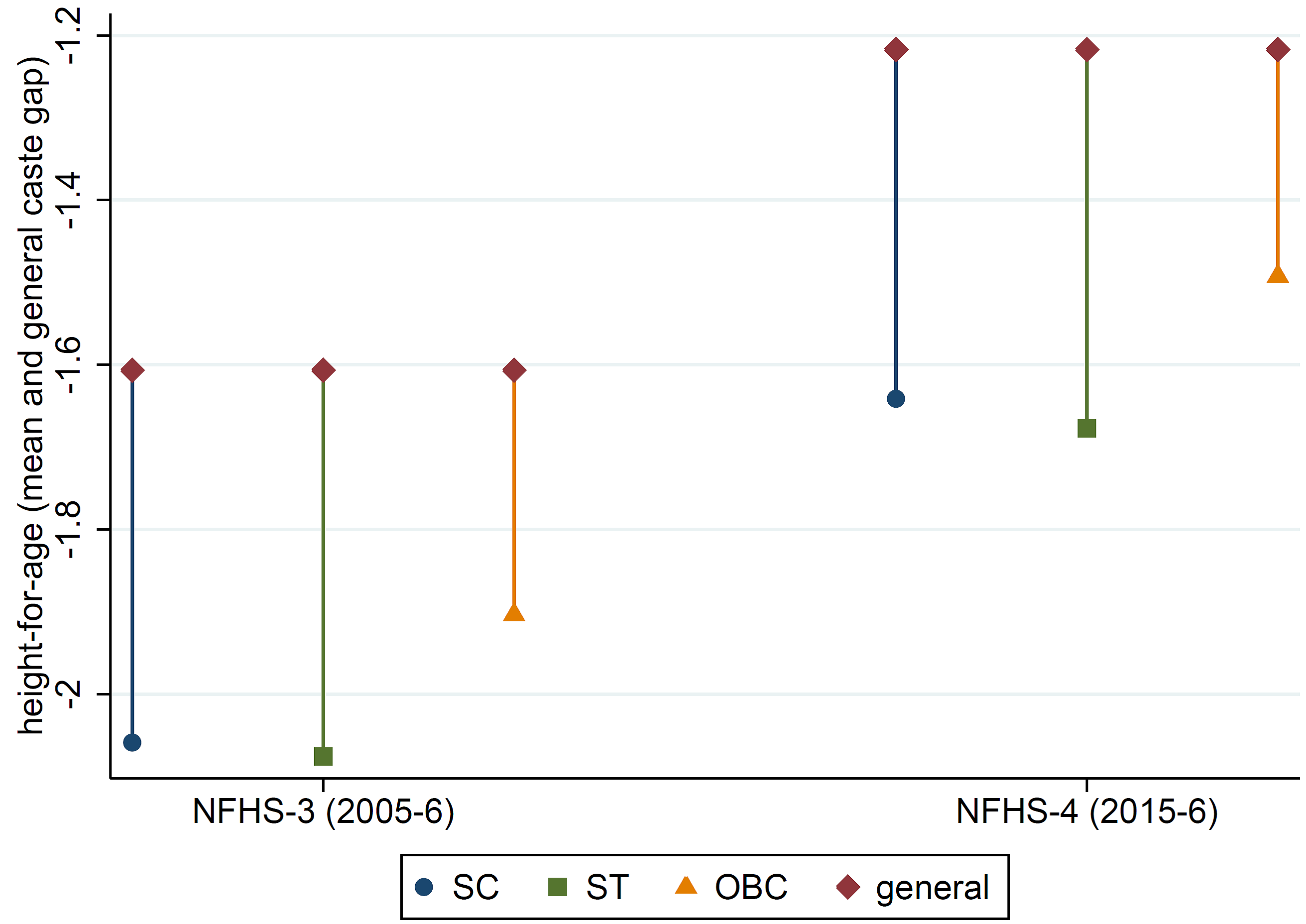

Although Indian children are now taller, on average, familiar patterns of discrimination remain intact. Caste differences in child height-for-age are particularly striking. Figure 1 below plots the average height-for-age of children belonging to Scheduled Caste (ST), Scheduled Tribe (ST), Other Backward Classes (OBC), and general caste, for the NFHS-3 and NFHS-4. Within each survey round, general caste children's dot is repeated three times to make the comparisons more visible.

Figure 1. Height-for-age by caste category, and gaps relative to general-caste children

Comparing the NFHS-3 and NFHS-4, it is clear that the dots shifted up. In other words, child height-for-age in each group increased, on average. Yet, the height gaps between children from disadvantaged castes and general castes remained similar: in both survey rounds, SC and ST children were about half of a standard deviation shorter than general-caste children, and OBC children were about three-tenths of a standard deviation shorter than general-caste children. So, despite rapid progress in economic and human development, caste gaps did not close. Further, SC and ST children in 2015 were no taller, on average, than general-caste children were in 2005. In our paper, we also discuss evidence that subtle patterns of sex discrimination also remain present in the NFHS-4 data.

Height in the rest of the world improved, too

The increase in the average height of children in India between 2005 and 2015 is important and worth celebrating. But, we conclude that the progress was modest and slow. This is because the increase must be considered in context. One context is India's rapid economic growth. For example, according to World Bank estimates, India’s real GDP (gross domestic product) per capita almost doubled. That is the sort of economic progress that one might expect to buy some more substantial improvements in human development – but familiar health disparities remain unchanged.

Another important context is international comparison. Over this decade, the average height of children in other stunted populations increased, too. As a result, India’s average child height-for-age stayed at the bottom -- especially in the disadvantaged northern plains states.

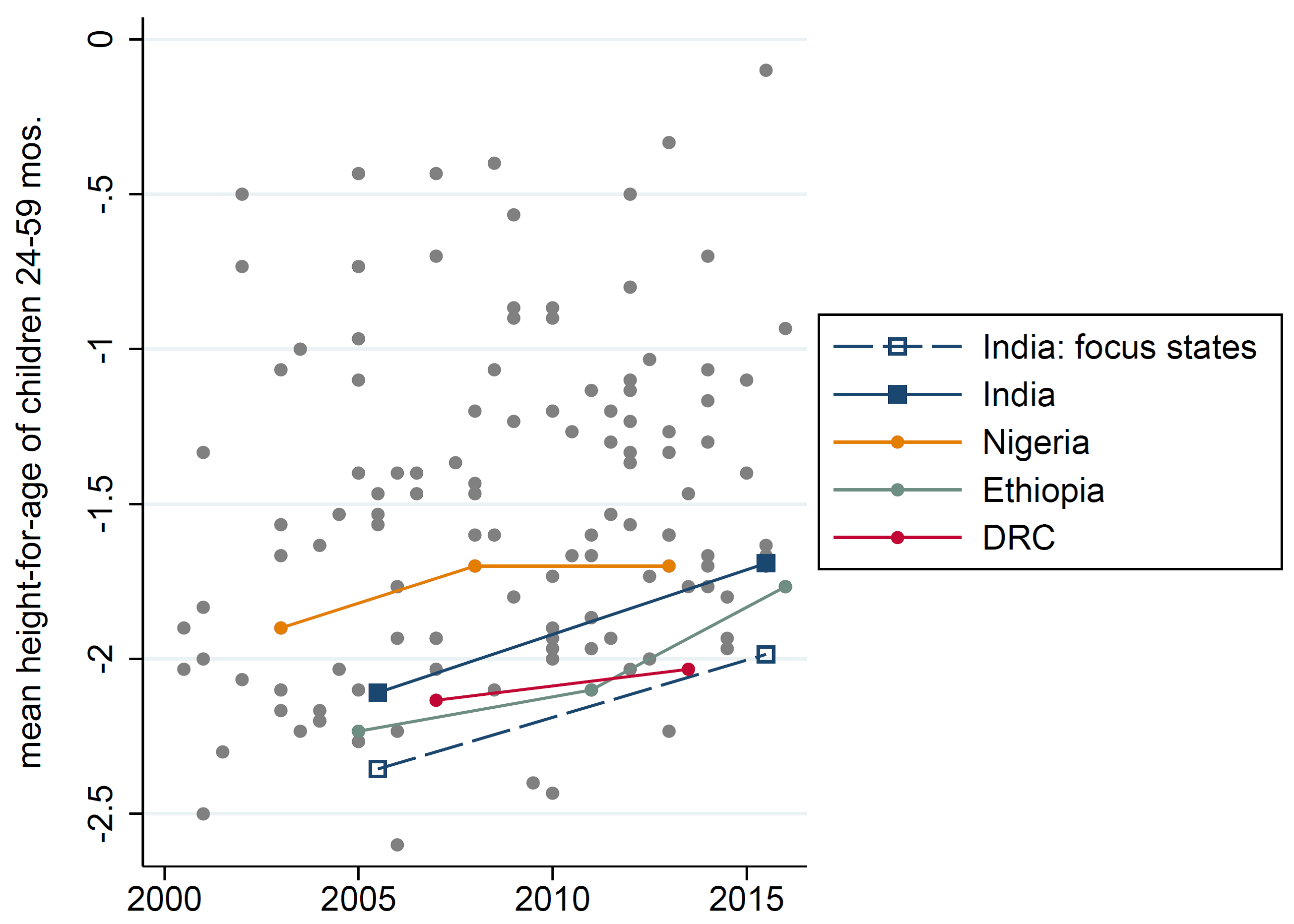

Figure 2. India’s change in child height-for-age, in international comparison

Source: NFHS-3, NFHS-4. Reprinted from Coffey and Spears (2018).

Notes: India’s NFHS-3 and NFHS-4 are represented by connected solid squares. The hollow squares and dashed line concentrate on four disadvantaged states that we call the ‘focus states’: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. Other DHS surveys are represented by grey circles.

Figure 2 compares the trend of average child height-for-age over time in India with the evolution of child height-for-age in the rest of the developing world studied by the DHS. Each point plots the mean (average) of height-for-age among children aged 24 to 59 months (after the height-for-age faltering of very early childhood has largely occurred), in a DHS survey conducted between 2000 and 2015. These points reflect 133 DHS surveys conducted in 70 different countries.

India was near the bottom of the child height-for-age distribution in 2005-06, and remained near the bottom of the distribution in 2015-16. Only a few countries had average child height as low as the ‘focus states’ in India did in 2005-06. No country measured in recent years has child height-for-age as low as the focus states in 2015-16. Average height-for-age did increase between 2005 and 2015 among children in the focus states, but not by enough to change their position at the bottom of the distribution, or to raise them above poorer large countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Why has progress been so slow?

The release of the NFHS-4 in January 2018 was rightly a cause for celebration among researchers and policymakers concerned with the health and well-being of India’s children. After all, there had been no high-quality, national, individual-level data about child height released in a decade. Unfortunately, though, what the NFHS-4 tells us about child height tempers reason to celebrate. Children grew taller, on average, by about four-tenths of a height-for-age standard deviation. But change was slow, relative to the size of the challenge, and familiar patterns of disadvantage, discrimination, and disease are still present. The hundreds of millions of children living in the focus states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan are particularly disadvantaged – they are at the bottom of the worldwide distribution of child height-for-age. Because one in five births worldwide now occurs in India, these facts about child height in the NFHS-4 are sobering news for anyone concerned about human well-being.

Policymakers need to know why economic development did not translate into more rapid improvements in child height. We find that this question is no mysterious puzzle. Improvements in height were limited because the determinants of height increased only slowly.

One important determinant is open defecation, which spreads germs and disease that keep children from growing to their full potential. In our 2017 book ‘Where India Goes’ (Coffey and Spears 2017), we described how the continuing importance of untouchability and caste-related norms of ritual purity and pollution mean that India has seen a much slower decline in open defecation than other developing countries. Indeed, between the NFHS-3 and the NFHS-4, open defecation in India went down by only 16.4 percentage points, from 55.3% to 38.9%. This small change in average exposure to open defecation would predict an increase in average height-for-age of only about 0.08 of a height-for-age standard deviation due to improved sanitation. This modest improvement would be about one-fifth of the increase in child height between 2005-06 and 2015-16. In other words, the small improvement in open defecation is consistent with the small change in child height.

Another critical factor is maternal nutrition. Women in India are underweight, especially at the ages when they are likely to get pregnant. The low social status of young women deprives them – and their babies – of the body mass that they need to grow and nurture the next generation. In a work-in-progress, one of us (Coffey 2018) has computed the pace of improvement in maternal nutrition implied by the NFHS-4. In 2015, 29% of pre-pregnant women were underweight. This figure is an improvement over the 2005 level of 42%. And yet, it implies that about 3 in 10 pregnant women started pregnancy underweight.

Unfortunately, policymakers should not be surprised by the slow pace of improvement in child height. The determinants of child height continue to change slowly. Moreover, the root causes of India's stunting reflect social forces and social inequality: gender discrimination in the case of maternal nutrition, and untouchability in the case of open defecation. These factors and forces should be at the centre of efforts to improve child health and height in India.

Notes:

- HUNGaMA is an initiative of Naandi Foundation that aims to create a hungama – Hindi for ‘stir’ or ‘ruckus’ – for change in the fight against hunger and ma

- Standard deviation is a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values from the mean value (average) of that set.

Further Reading

- Coffey, Diane (2015), “Prepregnancy body mass and weight gain during pregnancy in India and sub-Saharan Africa”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(11): 3302-3307.

- Coffey, D (2018), ‘Changes in maternal health in India: 2005-2015’, Working paper.

- Coffey, D and D Spears (2017), Where India goes: Abandoned Toilets, Stunted Development and the Costs of Caste, Harper Collins.

- Coffey, Diane and Dean Spears (2018), “Child Height in India”, Economic & Political Weekly, 53(31): 87-94. Available here.

- Coffey, Diane and Dean Spears (2018b), “Open Defecation in Rural India, 2015-16: Levels and Trends in NFHS-4”, Economic & Political Weekly, 53(9).

- Coffey, Diane, Dean Spears and Sangita Vyas (2017), “Switching to sanitation: understanding latrine adoption in a representative panel of rural Indian households”, Social Science & Medicine, 188: 41-50. Available here.

- Ghosh, Arabinda, Aashish Gupta and Dean Spears (2014), “Are Children in West Bengal Shorter Than Children in Bangladesh?”, Economic & Political Weekly, 48(8): 21-24. Available here.

11 February, 2019

11 February, 2019

By: Ramji 12 February, 2019

wonderful analysis, so how to record the girls boys heights data by Govt, should the govt record the height annually thru aadhar card, bank account, insurance policy renewal, passport holders