Community toilets in slums are often poorly maintained, and upgrading facilities is difficult due to low willingness-to-pay among potential users and ‘free riding’. Based on an experiment in Uttar Pradesh, this article examines the impact of one-time facility upgrade and cash incentives to caretakers. While there are improvements in the quality of facilities and reduced free-riding, more residents practise open defecation, with poor public health outcomes.

The Sustainable Development Goals highlight the importance of ensuring access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable basic services by 2030. However, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the provision of a wide array of basic services is limited by poorly maintained public infrastructure, from unreliable electricity grids to unsafe water and sanitation facilities (United Nations, 2020).

Limited investment in maintenance, mixed with low private willingness-to-pay for use and pervasive ‘free-riding’,1 can induce a ‘poor-maintenance trap’: Coordination failure between users and providers, drives effective prices for use below the marginal cost of operation, jeopardises incentives to invest in maintenance, reduces private valuations further, and sustains bad-quality public infrastructure (Banerjee et al. 2008, Berryet al. 2020, Burgess et al. 2020, Greenstone and Jack 2015). This vicious cycle is becoming an increasing concern in richer countries as well (Brutscher and Kappeler 2018, Garemo and Mischke 2013).

Low-quality basic services deriving from poorly maintained facilities, often generate dangerous threats to public health (Bartram et al. 2005), low levels of human capital, and persistent poverty (Currie and Vogl 2013, Ghatak 2015). Residents of densely populated informal settlements or ‘slums’, home to more than one billion people worldwide mostly in LMICs, are particularly affected (Marx et al. 2013).

How appropriate basic services can be guaranteed for these populations through well-maintained public infrastructure, remains an open question. While the World Bank estimates that US$ 4.2 trillion could be saved by investing in more resilient infrastructure to avoid costly upgrades (Hallegatteet al. 2019), we are yet to learn how obstacles leading to poor maintenance can be overcome (Duflo et al. 2012).

Incentivising public infrastructure maintenance to improve public service delivery

In a recent study (Armand et al. 2021), we ask whether externally incentivising maintenance can sustainably improve the quality of public infrastructure. The context is one of community toilets in India. This sanitation infrastructure, typically operating on a pay-to-use basis, provides slum residents a valued public health service. In slums, community toilets are considered the most appropriate medium-term solution for access to sanitation, a first-order issue with more than 700 million urban residents worldwide lacking access to private sanitation facilities and resorting to open defecation (Joint Monitoring Programme, WHO (World Health Organization)-UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), 2017).

Nevertheless, community toilets remain a typical example of the poor-maintenance trap. Facilities are degraded, dirty, and with a widespread presence of bacteria harmful to health. Upgrading facilities is challenging given the low willingness-to-pay among potential users and a high prevalence of free riding.

To incentivise improvements in infrastructure quality, we analyse two different interventions. First, the ‘maintenance’ intervention offered a one-off grant at the facility level, followed by a significant bimonthly financial reward to the facility’s caretaker, the person in charge of its maintenance. The reward is equivalent to 40% of the caretakers’ monthly salary and is conditional on keeping the facility clean.

Second, the ‘maintenance plus sensitisation’ intervention supplemented the maintenance intervention with an intensive sensitisation campaign to raise awareness among potential users about the importance of a well-kept facility, and of avoiding free riding to support good services.

The effectiveness of each intervention was evaluated in a field experiment that randomly allocated interventions (including a pure ‘control’ group, who do not receive either intervention) across 110 catchment areas of community toilets in slums of Uttar Pradesh. From April 2018, over a period of 18 months, responses from both sides of the market were recorded, using survey data on community toilets and slum residents, objective measurements of infrastructure quality and free riding, laboratory tests to measure bacteria prevalence, and behavioural measurements among potential users and caretakers using lab-in-the-field experiments.

Main findings

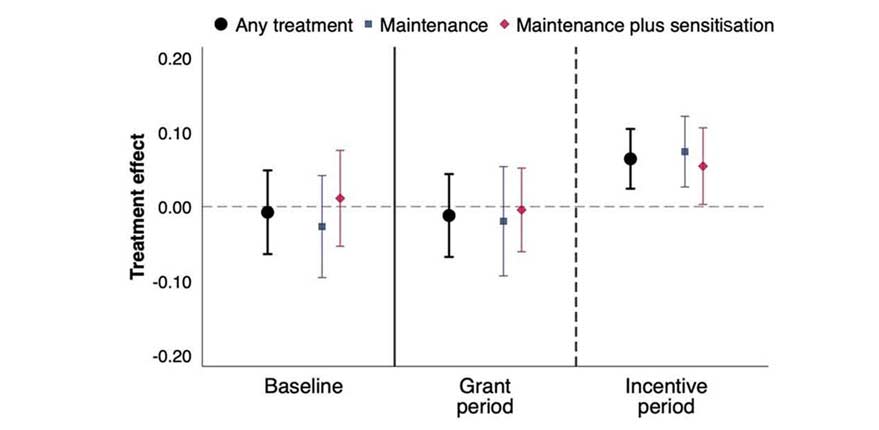

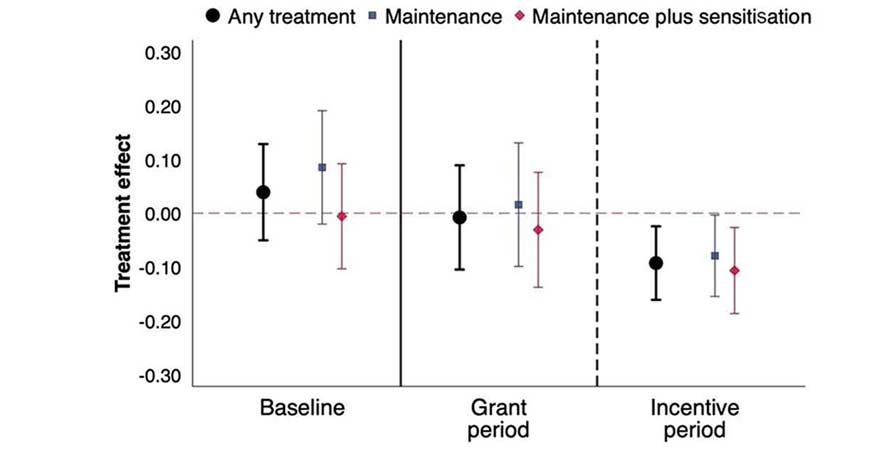

The maintenance intervention generated sustained improvements in the observed quality of facilities, accompanied by a significant reduction in free riding among users by 18 percentage points compared to the control group (Figure 1). These effects emerged only after the period in which the maintenance grant was offered (grant period), and once caretakers were incentivised financially to deliver higher quality (incentive period). This result is in line with other studies showing that cash incentives matter in the social and public sector (Bandiera et al. 2012, Burgess et al. 2012).

Figure 1.Effects on infrastructure quality (top panel) and free riding (bottom panel)

Notes:(i) Each panel presents estimates of ‘treatment effects’ based on OLS (ordinary least squares) regressions2 at the community-toilet level. (ii) Confidence intervals3 are built using statistical significance at the 10% level. (iii) Baseline includes the measurement at baseline; ‘Grant period’ includes the measurement taken after the implementation of the one-off maintenance grant but before the implementation of incentives to community toilet caretakers; and ‘Incentive period’ pools all follow-up measurements collected once the incentives were introduced.

While potential users perceive the improvements, incentivising maintenance has no effect on either the way they value use or their attitudes towards maintenance and cooperation. The incentive-compatible measure of willingness-to-pay for community toilet use was marginally reduced with the maintenance intervention, in line with a (temporary) crowding-out effect of external funding. Reductions in free riding from incentivising maintenance come at the cost of user selection imposed by providers, with a small decrease in traffic and without large increases in revenues. Providers also respond strategically to incentives by spending more time collecting fees and supervising the cleaning of the facility and less time in operating activities (conducting repairs, cleaning the facility, or spending time with the manager).

Citizens’ mobilisation is increased when external funds are transferred to improve the local facility. Slum residents respond to the maintenance intervention by asking local politicians for public intervention in the operation and maintenance of community toilets. The increase is large, at 50% over the control mean (average).

While citizen mobilisation has been shown to be responsive to information in other contexts (Banerjee et al. 2020, Ferraz and Finan 2011), adding a sensitisation campaign to the maintenance intervention has no effects beyond increasing health awareness. These results shed light on the political economy of public service delivery in slums, and suggest that slum residents treat access to sanitation as a right rather than a service to purchase.

Should access to basic services be fully subsidised in slums?

A crucial question for policymakers in developing countries is whether the delivery of basic services in the poorest and most marginalised areas should be fully covered under the governments’ budgets, rather than requiring private contributions.

For community toilets, in the current maintenance model financed by user fees, revenues from completely eradicating free riding among potential users would cover the status-quo operation and maintenance costs plus the cost of the maintenance intervention (Armand et al. 2021). While reducing free riding favours financial sustainability, coordination between users and providers does not seem feasible.

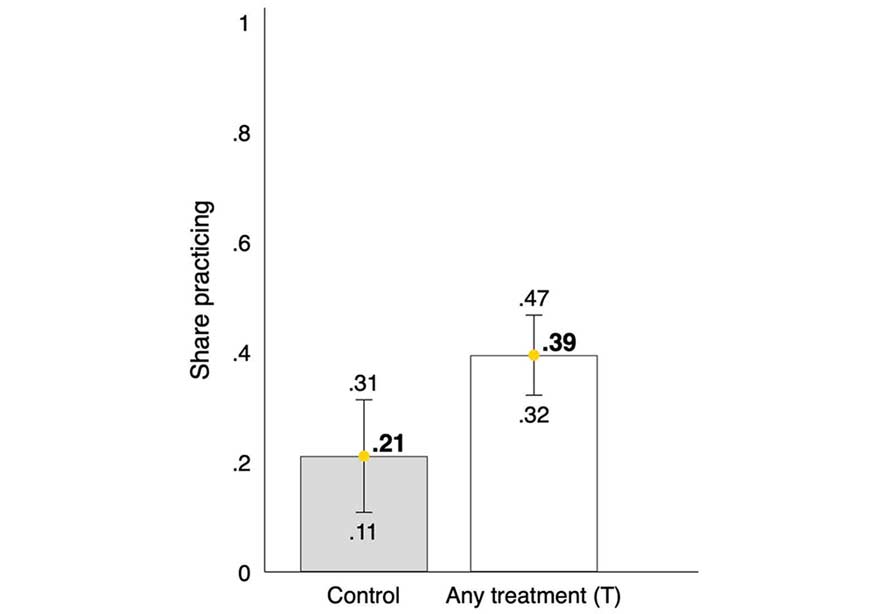

User selection can compromise public health. In treated areas, the average share of respondents who practised open defecation a year after the start of the study was 18 percentage points larger than in control areas (Figure 2). In line, the share of slum residents reporting positive health expenditures increased in response to the intervention. Such unintended consequences of subsidy provision have also been shown for India’s food subsidy programme (Kaushal and Muchomba 2013).

Figure 2. Effect on open defecation

Notes:(i) The figure shows the share of slum residents practising open defecation the day before the interview, estimated using a ‘list-randomisation’ technique. Shares are estimated as the difference in the number of items reported as ‘true’ by respondents who faced a long list (which includes the sensitive behaviour), and the respondents who faced a short list (which excludes the sensitive behaviour). We compute this average separately in the control group and in any treatment group. (iv) Confidence intervals are built using statistical significance at the 10% level.

Given the large health externalities of open defecation and the poor health conditions in slums, the government should consider providing free access to community toilets. Fully subsidising community toilets, however, is closely related to the ability of the local government to raise tax revenues and to redistribute them towards users that have little political representation (Besleyet al. 2021).

At the same time, providing community toilets for free to all residents can disincentivise its adoption or can overcrowd facilities. In Uttar Pradesh, free-to-use community toilets were also found in degraded state (Armand et al. 2020).

As the prevalence of private access to sanitation is low and coordination fails in the presence of overcrowding (Banerjee et al. 2008, Chidambaram 2020), a model with fully subsidised public infrastructure should consider imposing restrictions on the number of users per facility and/or enacting monitoring mechanisms to ensure that facilities are preserved by users.

A version of this article first appeared on VoxEU.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- In social sciences, the free-rider problem arises when some of those who avail of public goods and services do not pay the prescribed amount for them, or underpay.

- OLS measures the effects of the treatment on infrastructure quality and free riding.

- A confidence interval is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects. A 90% confidence interval (or confidence interval with statistical significance at the 10% level), means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 90% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Further Reading

- Armand, A, B Augsburg and A Bancalari (2021), ‘Coordination and the poor maintenance trap: An experiment on public infrastructure in India’, CEPR Discussion Paper Discussion Paper 16284.

- Armand, A, B Augsburg, A Bancalari and B Trivedi (2020), ‘Community toilet use in Indian slums: Willingness-to-pay and the role of informational and supply side constraints’, 3ie Impact Evaluation Report 113.

- Bandiera, O, K Jack and N Ashraf (2012), ‘No margin, no mission? Motivating agents in the social sector’, VoxEU, 13 March.

- Banerjee, A, N T Enevoldsen, R Pande and M Walton (2020), ‘Public information is an incentive for politicians: Experimental evidence from Delhi elections’, NBER Working Paper 26925.

- Banerjee, A, L Iyer and R Somanathan (2008), ‘Public action for public goods’, in T P Schultz and J Strauss (eds.), Handbook of Development Economics (Volume 4).

- Bartram, Jamie, Kristen Lewis, Roberto Lenton and Albert Wright (2005), “Focusing on improved water and sanitation for health”, Lancet, 365(9461): 810-12.

- Berry, James, Greg Fischer and Raymond Guiteras (2020), “Eliciting and utilizing willingness to pay: Evidence from field trials in Northern Ghana”,J ournal of Political Economy, 128(4): 1436-73.

- Besley, T, C Dann and T Persson (2021), ‘State capacity and development clusters’, VoxEU, 18 June.

- Brutscher, P-B and A Kappeler (2018), ‘Addressing Europe’s infrastructure gaps’, VoxEU, 18 April.

- Burgess, Robin, Michael Greenstone, Nicholas Ryan and Anant Sudarshan (2020), “The consequences of treating electricity as a right”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1): 145-69.

- Burgess, S, P Carol, M Ratto, E Tominey and S Von Hinke Kessler Scholder (2012), ‘On the use of high-powered incentives in the public sector’, VoxEU, 6 September.

- Chidambaram, Soundarya (2020), “How do institutions and infrastructure affect mobilization around public toilets vs. piped water? Examining intra-slum patterns of collective action in Delhi, India”, World Development, 132: 104984.

- Currie, Janet and Tom Vogl (2013), “Early-life health and adult circumstance in developing countries”, Annual Review of Economics, 5(1): 1-36.

- Ferraz, Claudio and Frederico Finan (2011), “Electoral accountability and corruption: Evidence from the audits of local governments”, American Economic Review, 101(4): 1274-311.

- Garemo, N and J Mischke (2013), ‘Infrastructure: The governance failures’, VoxEU, 30 March.

- Ghatak, Maitreesh (2015), “Theories of poverty traps and anti-poverty policies”, World Bank Economic Review, 29: S77-S105.

- Greenstone, Michael, and B Kelsey Jack (2015), “Envirodevonomics: A research agenda for an emerging field”, Journal of Economic Literature,53(1): 5-42.

- Hallegatte, S, J Rentschler and J Rozenberg (2019), Lifelines: The resilient infrastructure opportunity, World Bank, Washington DC.

- Joint Monitoring Programme WHO-UNICEF (2017), ‘Monitoring: Sanitation’, WHO and UNICEF.

- Kaushal, N and F Muchomba (2013), ‘Nutritional impact of India’s food subsidy programme’, VoxEU, 24 December.

- Marx, Benjamin, Thomas Stoker and Tavneet Suri (2013), “The economics of slums in the developing world”, Journal of Economic Perspectives,27(4): 187-210.

- United Nations (2020), Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations Economic and Social Council.

08 October, 2021

08 October, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.