Following the budget speech, Deepak Mishra weighs in on the extent to which the three goals of higher growth, better distribution, and stability were met. He discusses the Finance Minister’s success in appeasing large sections of the population through better targeting of subsidies and deft tinkering of tax policy. He concedes that although this year’s budget is a step in the right direction, it does not aim for bold structural reforms or address issues such as stagnant trade performance.

The 2023-24 Union Budget is likely to be best remembered for giving everyone something to feel good about, without resorting to reckless and populist policies. It seems to have given equal weightage to three interrelated goals – higher growth, better distribution (or more inclusion), and stability – which is the right call in the given context.1 While the programmes and schemes under each priority make considerable sense, the budget falls short of announcing any bold structural reform to tackle some of the binding constraints facing the economy, especially those that can significantly improve the country’s competitiveness.

The budgetary trade-offs

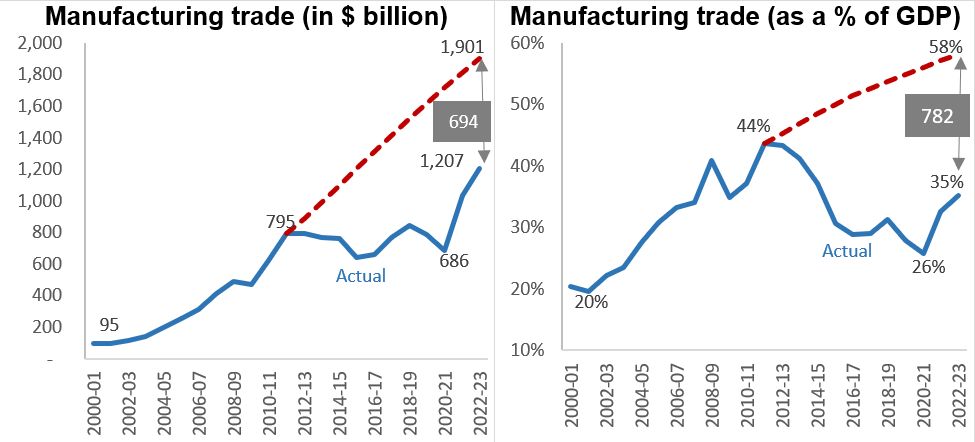

Budgets are about trade-offs. The goal of the finance minister is to allocate limited financial resources across competing demands to maximise national welfare. Like all previous budgets, the 2023-24 Union Budget had to deal with the inherent trade-off between three interrelated goals. As is customary, the budget contained announcements of several new programmes, strengthening of existing programmes, and tax and tariff changes to achieve these three goals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The trinity of competing goals, and how it was addressed by the budget

How successful was the budget in achieving these objectives?

There are two broad ways to assess the success of the budget using this framework. The first is to assess the importance assigned to each of the three priorities against the most pressing needs of the country. The second is to examine the relevance and expected impact of the announced programmes and schemes under each priority.

The budget was announced in the backdrop of four key developments. First, the Indian economy has been performing quite well, often seen as resilient amidst multiple global crises. Second, India currently holds the G20 Presidency, and is expected to play a leadership role in steering the global economy through its many challenges. Third, while India’s economy is doing well at the aggregate level, parts of it are in considerable distress (mainly the rural economy, the informal sector and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs)), and the unemployment rate is unacceptably high among the youth and women. Finally, while the post-Covid recovery has been strong, the structural constraints that led to lower growth prior to Covid need to be addressed, especially the slowdown in trade and the competitiveness of India’s manufacturing sector.

The budget appears to have given equal weight to growth, distribution and stability. Going by the expenditure allocation across initiatives, the ‘growth’ pillar seems to have been accorded the highest importance. However, if one goes by the number of schemes and programmes announced, and the share of the budget speech allocated to a single priority, the ‘distribution’ pillar seems to have received the maximum attention. As far as the ‘stability’ pillar is concerned, by pegging the fiscal deficit at 5.9% of GDP in FY2023-24, recommitting to the gliding path of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, and keeping market borrowing at the same level as last year, the Finance Minister has provided enough assurance to investors that macroeconomic fundamentals will remain strong for the foreseeable future.

Does the budget have something for everyone?

Mathematically, a budget is supposed to be a zero-sum game: if one group gets a massive increase in allocation, other groups will have to contend with a smaller increase or even a reduction. Similarly, if one sector gets a tax break, other sectors may have to fork out more. And if everyone gets more allocation or tax rebates, then the government has to borrow more from the market to balance the budget. Yet, Finance Minister Sitharaman seems to have done the impossible: the 2023-24 Union Budget appears to have given everyone something to feel good about, while ensuring that the fiscal deficit – the difference between expenditure and revenue, plus interest payments – as a share of GDP comes down.

How did the Finance Minister manage to do it? These are three possible explanations:

- With the Covid-19 pandemic out of the way, and the softening of global commodity prices, the Finance Minister has a window of opportunity to roll back many subsidies by a significant amount. For example, food subsidies have been reduced from Rs. 2.87 trillion2 in FY2022-23 to Rs. 1.97 trillion in FY2023-24, and fertiliser subsidies from Rs. 2.25 trillion to Rs. 1.75 trillion. Similarly, MNREGA outlay has been reduced from Rs. 894 billion last year to Rs. 600 billion this year. Purely from an expenditure allocation perspective, the farm sector and rural poor are at a disadvantage, though they will gain from the slew of new initiatives announced.

- Some of the tax changes appear to be revenue neutral. While the budget has reduced the surcharge on income tax for high net-worth individuals, it has also closed many loopholes in the personal income tax regimen. Similarly, it has reduced basic custom duties, while simultaneously increasing cesses and surcharges, resulting in no net loss to the treasury. So, while the budget has given something to the taxpayers to cheer about, it has clawed back other benefits to ensure no significant revenue loss to the treasury.

- The final explanation lies in the ‘money illusion’: the allocation for several sectors (mainly social sectors) has increased in nominal terms, but has fallen in real terms or as a share of GDP.

In short, the Finance Minister doesn’t have a magic wand that can make everyone happy at the same time, but the expectations of lower global commodity prices, better targeting of subsidies, clever use of tax instruments and the advantage of a growing economy have helped spread budget cheer to a very large segment of the population.

Addressing the binding constraints

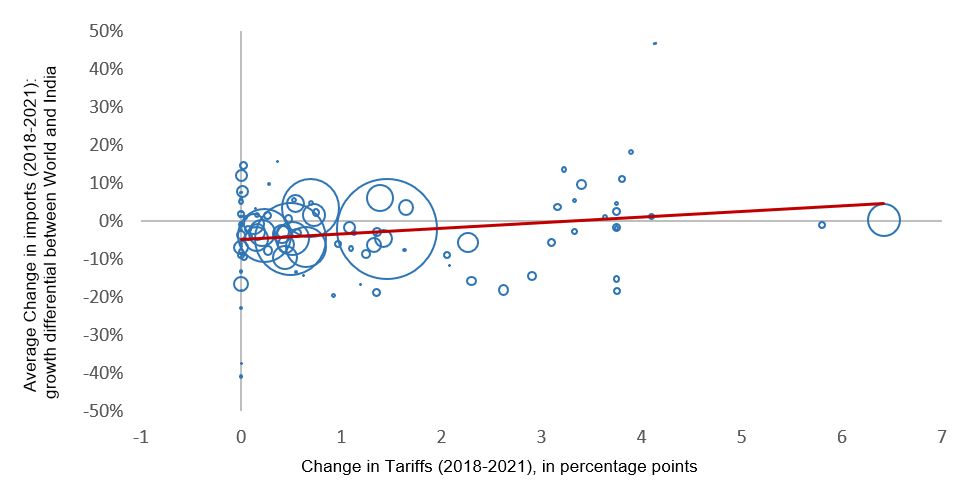

While the programmes and schemes under each priority make considerable sense, it is not obvious whether they are addressing some of the binding constraints facing the economy. Let me illustrate this using the programmes announced under the growth pillar. The budget contains several initiatives that should contribute to growth: higher capital investment, digital public infrastructure for agriculture, the Skill India digital platform, national apprenticeship promotion scheme, developing cluster-based value chains using public-private partnerships, establishment of centres for research on artificial intelligence, some modification in custom duties, and so on. However, it is not obvious if these problems will help to address one of the biggest drags on growth, namely the stagnant trade performance. As shown in Figure 2, had exports and imports grown at even 50% of the rate at which they grew between FY2000-01 and FY2010-11, India’s trade would have been close to $1.9 trillion – nearly $700 billion more than it is today.

Figure 2. India’s goods trade, FY2000-01 to FY2022-23

Sources: Reserve Bank of India, Economic Survey 2023-24, and the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

Notes: i) The dotted red lines represent the projected trade levels, if trade was growing at 50% of the rate it grew from 2000-2011. ii) The figures in grey boxes indicate the difference between the projected or potential manufacturing trade value with current actuals, in US$ billions. For the left panel, the difference is $694 billion. For the right panel, the estimated difference is $782 billion

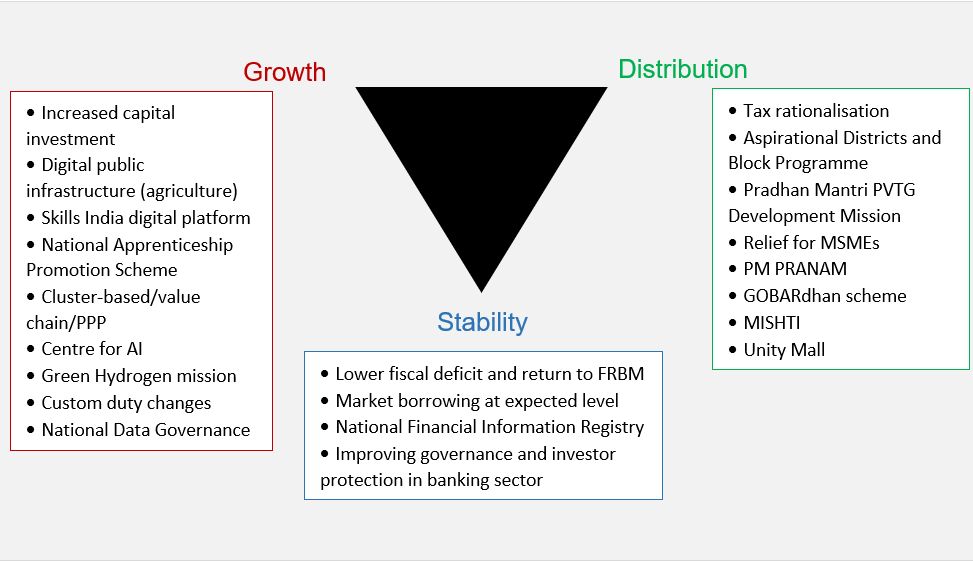

The budget makes a good start of reducing basic custom duties in key intermediate products, but the reduction is too small and too ad hoc to reverse the weak trade performance. The budgets for the past several years, against the advice of most trade economists (including those who have held important positions in the government), have increased the custom duties across many sectors. This, along with the decision to not sign any new trade agreements, has squeezed the country’s competitiveness. As shown in Figure 3, the ill-advised increase in custom duties hasn’t even translated into lower imports – if anything, imports have increased! Thankfully, this year’s budget appears to have put an end to this damaging practice. In fact, it has reduced custom duties for several products used as intermediate inputs in industries receiving Production Link Incentives (PLIs). While the reduction in duties is modest and random, if future budgets continue to lower duties to what they were in the early 2010s, it could signal a decisive break from India’s recent protectionist stance.

Figure 3. Increase in tariffs and the corresponding change in imports

Source: World Trade Organization, International Trade Centre, Economic Survey 2023-24, and the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

The bottom line

Given that the 2023-24 Union Budget is the last full budget before the next general election, people expected a mixed performance: economists were worried that there would be too many freebies; investors were anxious that the extent of fiscal consolidation would be compromised; and businesses were concerned that infrastructure spending may have been sacrificed at the altar of election giveaways. But the Finance Minister has pleasantly surprised us all by giving everyone something to feel good about, without resorting to irresponsible policies or seeking excessive populism. With the world economy facing multiple crises simultaneously, and the Indian economy struggling to return to a high growth path that is also inclusive, the budget seems to have struck the right note between growth, distribution and stability. But for those hoping for bold structural reforms to return India to the 8% growth path, the wait just got a bit longer.

Notes:

- These three priorities closely resemble the three pillars in the budget document referred to as the “Vision for Amrit Kaal”: opportunities for citizens, growth and job creation and strong and stable macro. These goals are interrelated, since measures to improve inclusion can lead to higher growth and vice-versa.

- 1 trillion equals 1 lakh crore.

03 February, 2023

03 February, 2023

By: Anil Kumar Kanungo 17 February, 2023

It's quite well written article. You emphasize a lot on growth and in your opinion, growth is one of the strongest pillars of this year's budget. I believe it's just not growth rather quality of growth that matters. In order to have quality of growth, the government needs to stress upon quality of investment. But over the years, I believe investment as a ratio of GDP is coming down which essentially reflects that our macroeconomic fundamentals are getting weaker. Looking forward to your considered opinion on this.