By March-end, countless migrant workers started fleeing India’s locked-up cities and trekking home to their villages amidst the Covid-19 crisis. Sarmistha Pal argues that government’s responses until now not only failed to cater to migrant workers’ needs, but also remain largely ineffectual in solving the cash constraints of their employers. These responses are costly as they are likely to give rise to more hunger and starvation, deaths, loss of productivity, firm closure, and ultimately mass unemployment.

The migrant crisis triggered by the lockdown policy of the government of India (GOI) to tackle Covid-19 is, once again, exposing India’s deep economic divide and apathy towards the marginalised poor. In this post, I assess the impact of government’s flawed policy responses to this crisis, taking account of concerns of both migrant workers and their employers.

Migrant workers are among the most vulnerable parts of India’s informal sector, which makes up about 90% of India’s workforce. There are more than 40 million migrant workers in the country. They are largely unorganised, and over-represented by people from the lowest castes. These workers escape poverty in their villages and migrate to cities and urban centres where they construct houses, cook food, serve in eateries, deliver takeaways, cut hair in salons, make automobiles, plumb toilets, deliver newspapers, and the like.

After a trial ‘janata curfew’ on 22 March, GOI declared a complete lockdown on 24 March. Within a week of the introduction of the lockdown, their workplaces were shut, and most employers and contractors who used to pay them vanished – according to a recent survey as high as 90% of these workers were not paid. Their savings are meagre, they have lost their livelihood, and they and their families have nothing to fall back upon. All they want is to return to their villages where perhaps they hope to survive with help from families and kinship networks. But the lockdown makes it impossible with all buses, trains, and taxis suddenly stopped. News reports said workers were stranded in railway stations. By 30 March, countless migrant workers started fleeing India’s locked-up cities and trekking home to their villages, despite being ill-treated by the police, and in one case even being sprayed with sanitisers. This contrasted starkly with the government’s response to the rich returning from abroad, who were offered immediate assistance, testing, and treatment.

It is difficult to believe that the government or its advisors were totally unaware of the potential impact of the lockdown on the sizeable group of migrant workers. While the Finance Minister announced the GOI relief package on 26 March, there was no provision for the migrant workers who work away from their homes. As the migrant problem grew out of control, the Home Minister ordered the states to stop the migrants leaving the cities. Consequently, many migrant workers were forced to be dependent on uncertain food handouts from some state governments, trade unions, or charities for survival; some reduced to begging. They were forced to live in shelters, or sleep on footpaths or under flyovers of the cities they served. When the Prime Minister (PM) extended the lockdown beyond 14 April and until 3 May, their desperation grew and many tried to flee and protest when harshly intercepted by the police.

Surely, all these could have been avoided easily if the government had cared to compensate for the costs of the sudden lockdown on these poor migrant workers. Buses could have been arranged, food and medicine provided, medical check-ups organised, and migrant workers taken to their destinations. This would have saved many lives and made lockdown successful, thus limiting the spread of the disease. But nothing was done and there is no rational explanation.

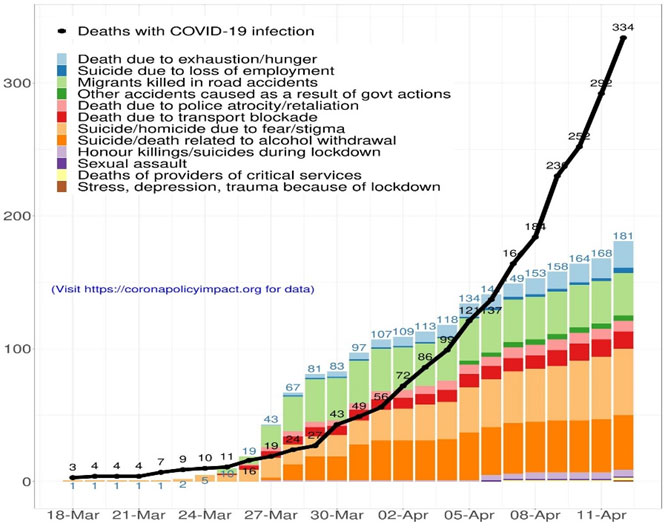

Figure 1. Trends in deaths by causes during the lockdown period.

What did the government achieve from the lockdown?

On 24 March, when the PM announced the three-week lockdown, the overall positive cases in India stood at 564. By 14 April, when it was scheduled to lift, the number of positive cases had gone up to 10,363. There is no obvious impact of the lockdown on the spread of the virus. In all likelihood, this is a lower bound of the actual positive cases, as the number of testing per million people remains abysmally low in India to date. Figure 1 further shows that rising incidence of Covid-19 deaths over the lockdown period has also been accompanied by rising deaths on various related accounts. Particularly noteworthy are the deaths on account of exhaustion/hunger, road accidents, transport blockage, suicide/homicide due to fear/stigma, many of which are direct results of the government’s flawed response to the migrant crisis and could have been averted, which would also minimise the efficiency losses of the lockdown.

This is not all as there are further knock-on effects. Without sufficient government support during the lockdown, a large proportion of these migrant workers are starving and suffering from malnutrition. Given the well-established link between nutrition and productivity, it is expected that malnourished workers prone to diseases will also have lower productivity, if and when the economy restarts, and factories reopen in May. The WHO (World Health Organization) reports that adequate nutrition can raise one’s productivity levels by 20% on average, and therefore malnourishment would cause about 20% loss of productivity. Even if the government policy of holding back the migrant workers in the cities help their employers to secure a local pool of migrant workers at low cost, government’s dogged refusal to support the migrant workers comes with a costly loss of productivity.

Low productivity of malnourished workers will eventually affect their prospective employers – the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) – who have been struggling since the 2016 demonetisation exercise, despite currently contributing to about 58% of GDP (gross domestic product). These companies are facing different problems – employee health and safety issue, decreasing demand, broken supply chain issue, weakening of long-term financial capacity, which in turn constrains their long-term investment.

Under pressure to facilitate the flow of more money to struggling MSMEs, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on 17 April announced a targeted long-term repo operation (TLTRO) of Rs. 500 billion aimed at small and mid-sized non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and micro finance institutions (MFIs). First of all, this relief package was announced after more than three weeks of the lockdown and no one knows when the money will reach the target MSMEs. It is estimated that an average SME in the US has about 27 days of cash to survive on average. While we do not have a corresponding estimate for the Indian MSMEs, a delay of three weeks before government announcement can prove fatal for many of these struggling MSMEs. In a statement, the Secretary General of Federation of Indian MSMEs has complained that banks are not disbursing funds to cash-poor firms despite RBI orders. Second, serious doubts remain about the demand for this new loan scheme from MSMEs, when future economic outlooks remain uncertain amidst the ongoing crisis of confidence in India’s financial sector since the collapse of the IL&FS (Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services) in late 2018. No one knows exactly how many MSMEs would actually apply for this bank loan scheme.

Export-sector firms had demanded for a comprehensive economic package for the industry to provide relief in payment of wages, statutory obligations, rentals, and utilities. In the absence of adequate government support to compensate for the unexpected costs, firm-level financial returns are unlikely to be sufficient to cover the social costs, that is, private costs of production of MSMEs plus the unexpected costs of the lockdown (including potential loss of workers’ productivity). If some of these firms go burst, large scale unemployment is inevitable. The latest CMIE report suggests that unemployment rate has been worsening fast since the lockdown and now stands at 26% in the third week of April. If the MSME issues remain unaddressed, we cannot rule out the possibility of mass unemployment even after the lockdown is lifted.

What should be done to compensate for the unexpected costs of lockdown?

The authorities say that the lockdown is key to saving lives, but the utter neglect of the concerns of both workers and employers is proving costly. On the one hand, government’s refusal to pay the quarantine incentives to migrant workers has hit their consumption badly. On the other hand, absence of prompt government action to cushion the cash constraints of MSMEs is likely to drive even viable firms out of business, raising the prospect of mass unemployment. Unexpected costs of the lockdown have thus inserted a wedge between social and private costs of workers and MSMEs. Without adequate government funded incentives, markets, on their own, will fail to account for the unexpected costs of the lockdown in these uncertain times.

Even if the migrant workers are held back in the cities after their jobs are gone, they need to be supported with food and shelter. Emergency issuance of temporary PDS (public distribution system) cards or universalising PDS (quite affordable given the huge stock of foodgrain with the Food Corporation of India) until the economy restarts could be a quick solution to avert starvation. The proposed loan scheme for MSMEs too seems unfit to ease their cash constraints (which is different from a solvency problem) urgently, and hence, may fail to generate the expected demand for the scheme. Instead, prompt cash transfers directly from the government to MSME accounts is likely to be more effective. Online GST (goods and services tax) payment accounts can be used to accomplish these cash transfers readily. Unnecessary delays to do so would lead to more hunger, starvation and deaths (in excess of Covid deaths), loss of productivity, closures of MSMEs, and ultimately mass unemployment. It is a race against time and all efforts need to be devoted now to ensure that this temporary shock does not turn into a much longer-term one.

The author has benefitted from discussions with Indraneel Dasgupta, Sugata Ghosh, and Bibhas Saha.

03 May, 2020

03 May, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.