Many low-income households in India have been pushed into poverty by high healthcare costs. Uptake of the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, the government-run national health insurance programme for below poverty line households, has been less than optimal. This article examines the impact of offering hospital insurance to a sample of above poverty line households in Karnataka. It finds significant peer effects in increasing insurance utilisation; hospital insurance however doesn’t have any significant effect on health outcomes.

Household financing of healthcare in developing countries is a significant challenge, especially for low-income families. In 2018, households in India paid 62% of health expenditures out-of-pocket (World Health Organisation, 2021). Many households are pushed into poverty by high health costs, and healthcare is often foregone due to financial concerns (Berman and Ahuja 2008).

To address these challenges, in 2008 the Indian government launched a publicly-financed national hospital-insurance programme for below-poverty-line households, called the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). The programme provided insurance largely for free. This decision was based, in part, on the concern that cost-sharing would reduce enrolment; however, uptake remained below 100% even with a nominal premium (Berg et al. 2019, Mukherji et al. 2012). Moreover, utilisation among enrolees was less than optimal (Garg et al. 2020). Had enrolment and utilisation been high, the fiscal cost would have been much greater, a common criticism of publicly-financed health insurance schemes in countries with low fiscal capacity (Oxfam 2008). The health impacts of utilisation are poorly understood, and this experience raises several pressing questions.

First, could lower middle income countries like India reduce pressure on public finances by offering the opportunity to buy unsubsidised, actuarially fair insurance without reducing programme uptake? Second, why was healthcare utilisation low among the newly insured? As with other new technologies, individuals (and even providers) may not know how to use it. Adoption may be slow and subject to learning-by-doing and information spillovers, as individuals learn from other users. And finally, does health insurance actually improve health in lower middle income countries?

The study

To address the questions above, we conducted a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) between 2013 and 2018 to study the impact of expanding hospital insurance eligibility under RSBY (Malani et al. 2021). The experiment offered above poverty line households, who lacked hospital insurance, access to RSBY. The study was conducted in the state of Karnataka: the sample included 10,879 households (comprising 52,292 members) in 435 villages, making this amongst the largest health insurance experiments ever conducted.

Treatment varied at two levels. First, sample households were randomised to one of four treatments:

i) Free RSBY insurance

ii) The opportunity to buy RSBY insurance at the actuarially fair price

iii) The opportunity to buy RSBY insurance, along with an unconditional cash transfer equal to the RSBY premium

iv) No intervention (control group)

These different treatments allow us to determine how premiums affect uptake, and shed light on the trade-off between greater uptake and higher government expenditure on insurance premium subsidies. The fraction of sampled households in each village that were randomised to receive treatment for each option of insurance access varied. This allows us to estimate the within-village spillovers from households that get access to insurance on enrolment of other households, and from households that enrol in insurance on utilisation of other households.

This spillover may be important through several potential channels. As insurance is a relatively new product in India and neighbours’ experience may affect enrolment or utilisation (Chatterjee et al. 2018, Debnath and Jain 2020). Alternatively, the limited supply of beds may affect access for households if neighbours’ utilisation is high relative to capacity.

The study included a baseline survey involving multiple members of each household, that was conducted 18 months before the intervention. Outcomes were measured twice, at 18 months and 3.5 years after the start of the intervention, to allow us to study both the short- and long-term effects of insurance. These two sets of outcomes may differ for various reasons, including learning-by-doing, the accumulation of health benefits from medical care (Black et al. 2017), negative experiences that lead households to stop utilising insurance, or crowd-out or congestion that builds up over time.

Effects of insurance access on uptake

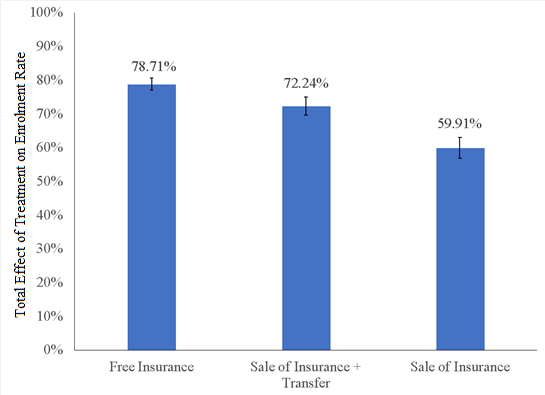

A wide array of health outcomes were measured, covering outcomes reported in many prior studies (Baicker et al. 2013, Haushofer et al. 2020), including mental health, mortality, and several biomarker outcomes. Our primary finding is that unsubsidised sale of insurance achieves relatively high uptake: accounting for spillover effects, the option to buy RSBY insurance increased uptake by 59.91% relative to the control group, while the unconditional cash transfer increased utilisation to 72.24% and the conditional subsidy to 78.71% (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effects of insurance access on insurance enrolment

Note: The black standard error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. A 95% confidence interval means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Utilisation of insurance: the effect of spillovers on early gains

The second finding is that although enrolment in insurance raised utilisation by 6 percentage points in the short run; however, many enrolled households were unable to use insurance to cover the costs of health care, not just due to supply-side constraints, but also demand-side obstacles such as households forgetting their card or trying to use RSBY at non-participating hospitals.

In addition, utilisation fell over time: six-month utilisation was just 1.60% in the free insurance group after 3.5 years. Instead of positive learning-by-doing effects, it seems that households were discouraged by the difficulty of using the new insurance product.

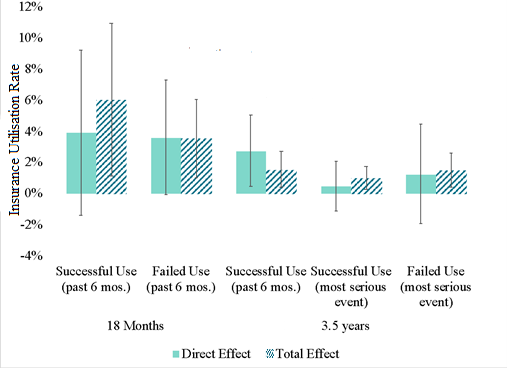

Finally, we found that spillovers play an important role in promoting insurance utilisation. Without those spillover effects, the overall effect of the intervention on utilisation would not be statistically significant (see Figure 2). This is consistent with other findings in the literature on insurance utilisation (Chatterjee et al. 2018, Debnath and Jain 2020) and suggests peer effects in learning how to utilise insurance.

Figure 2. Effects of insurance enrolment on insurance utilisation

Notes: i) The first two bars on the x-axis correspond with the outcomes measured at 18 months; the last three bars correspond with the outcomes measured at 3.5 years. ii) Regression coefficients were transformed to show percentage point changes from the control group. iii) The direct effect only includes the coefficient on treatment. iv) The total effect is constructed as the sum of the direct effect and 0.9*(spillover effect), with spillover effect being the estimated effect on a treated household of assigning all other sample households in the village to the same treatment. v) Successful use means the household used RSBY to pay for medical treatment. vi) Failed use means that the household attempted to use RSBY to pay for care but were unable to (for many possible reasons). vii) The most serious event is defined as an accident which caused a household member to miss at least two days of work, a childbirth or a stillbirth. If none of those occurred, it is defined as the most expensive health event or the one that led to the longest hospital stay.

Impact of insurance on health outcomes

Overall, we find that, after adjusting for multiple tests, health insurance failed to show statistically significant treatment effects on health-related outcomes across the two rounds of surveys. There are several possible explanations for this finding: firstly, too few households successfully used insurance to move the needle on health outcomes, underscoring that merely access is not enough in the face of obstacles to successful use. Low quality of health care (Das et al. 2012) is also a possible explanation.

A second possibility, considering the clinically-significant health effects (which are, on average, 11% of the standard deviation for each outcome), is that even this study, which is amongst the largest health insurance experiments ever conducted, may lack adequate power to estimate the health effects of insurance (Goldin et al. 2019, Kaestner 2021). Recent research has shown that a sample size of millions may be required to find the effects on rare outcomes (Goldin et al. 2019).

Nevertheless, these findings have implications for the implementation of public insurance in India, and perhaps other low- and middle-income countries. First, requiring higher-income households to pay for public insurance may reduce the fiscal cost of public health insurance, without seriously compromising uptake. Second, demand- and supply-side barriers to utilisation may significantly curtail the efficacy of an ambitious health insurance programme. Third, spillover effects on insurance utilisation point to the importance of understanding the role of peers in the marketing of health insurance and other such financial products.

This article is published in collaboration with VoxDev.

Further Reading

- Baicker, Katherine et al. (2013), “The Oregon experiment — effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes”, New England Journal of Medicine, 368(18): 1713-1722.

- Berg, Erlend, Maitreesh Ghatak, R Manjula, D Rajasekhar and Sanchari Roy (2019), “Motivating knowledge agents: Can incentive pay overcome social distance?”, The Economic Journal, 129(617): 110-142. Available here.

- Berman, Peter and Rajeev Ahuja (2008), “Government health spending in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 46: 26-27.

- Black, Bernard, Jose-Antonio Espín-Sánchez, Eric French and Kate Litvak (2017), “The long-term effect of health insurance on near-elderly health and mortality”, American Journal of Health Economics, 3(3): 281-311.

- Chatterjee, Chirantan, Radhika Joshi, Neeraj Sood and P Boregowda (2018), “Government health insurance and spatial peer effects: New evidence from India”, Social Science and Medicine, 196: 131-141.

- Das, Jishnu et al. (2012), “In urban and rural India, a standardised patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps”, Health Affairs, 31(12): 2774-2784.

- Debnath, Sisir and Tarun Jain (2020), “Social connections and tertiary health-care utilisation”, Health Economics, 29(4): 464-474.

- Garg, Samir, Kirtti Bebarta and Narayan Tripathi (2020), “Performance of India’s national publicly-funded health insurance scheme, Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), in improving access and financial protection for hospital care: Findings from household surveys in Chhattisgarh state”, BMC Public Health, 20(1): 949.

- Goldin, Jacob, Ithai Lurie and Janet McCubbin (2019), “Health Insurance and Mortality: Experimental Evidence from Taxpayer Outreach”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(1): 1-49.

- Haushofer, Johannes, Matthieu Chemin, Chaning Jang and Justin Abraham (2020), “Economic and psychological effects of health insurance and cash transfers: Evidence from a randomised experiment in Kenya”, Journal of Development Economics, 144(C). Available here.

- Kaestner, Robert (2021), “Mortality and science: A comment on two articles on the effects of health insurance on mortality”, Econ Journal Watch, 18(2): 192-211.

- Malani, A et al. (2021), ‘Effect of health insurance in India: A randomised controlled trial’, NBER Working Paper No. w29576.

- Mukherji, Arnab, Prateek Rathi and Gita Sen (2012), “Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana: Evaluating utilisation, roll-out and perceptions in Amaravati district, Maharashtra”, Economic and Political Weekly, 47(39): 57-64.

- Oxfam (2008), ‘Health insurance in low-income countries: Where is the evidence that it works?’, Joint NGO Briefing Paper.

01 July, 2022

01 July, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.