Although many governments introduced additional benefits as part of existing welfare schemes for Covid-19 relief, there is often a significant gap between the introduction of, and access to these benefits. Based on a field experiment in Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh, this article shows that simple, low-cost, information provision interventions can improve the accuracy of households' beliefs about the entitlements they are eligible for and increase the amounts they actually receive, improving beneficiaries’ food security and well-being.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the livelihoods of millions of households, resulting in widespread poverty and food insecurity (see Gentilini et al. (2021) and Vyas (2020), among others). To mitigate these pernicious effects, many governments have introduced additional benefits as part of their existing welfare schemes. However, there is often a significant gap between the introduction of these measures and access to the benefits they entail – potentially due to ineffective communication, lack of awareness among the intended beneficiaries, complexity of the schemes, and corruption. It is therefore crucial to understand both the nature of these gaps and the measures that governments can take to ensure that programmes effectively reach their intended beneficiaries.

In a recent study (Amirapu et al. 2022), we seek to understand whether providing personalised information on access to emergency government benefits improves the knowledge, uptake, and well-being of citizens. To answer these questions, we conducted a field experiment in the city of Kanpur1 in the populous north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh between September 2020 and February 2021.

Government programmes that provided additional aid

We focus on three large programmes – the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) and the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY).

PMGKAY was announced on 26 March 2020, just days after the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown was implemented, under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana welfare package for Covid-19. Under this scheme, all ration cardholders – who were already beneficiaries of the public distribution system – were eligible to get five kilograms (kg) of wheat and rice (per person, per ration card) along with 1 kg of pulses (per household) free of cost, on top of any previous entitlements. PMUY was originally launched in 2016, to provide free liquified petroleum gas (LPG) connections to women in households with a below poverty line card. PMUY was extended starting from July 2020, allowing the recipients to obtain free-of-cost refills for a period of three months, later extended to March 2021. Under JDY, women already holding JDY accounts were eligible to receive Rs. 500 per month for three months, from April to June 20202. Additionally, the scheme allowed for poor widows, disabled people, and senior citizens to receive Rs. 1000 for three months into their JDY accounts.

In sum, all three programmes provided additional aid on top of existing entitlements. The additional entitlements formed part of a larger package of relief measures, which were announced at a similar time, and which had differing eligibility requirements. Given the pace of the roll out under the extenuating circumstances at the time, it is plausible that eligible recipients might have faced confusion and uncertainty about what aid (if any) they would be eligible for and able to receive.

The study

We conducted a baseline survey during September-October 2020 to assess the knowledge that intended beneficiaries had regarding these three programmes. We find that beneficiaries had relatively accurate knowledge regarding which programmes they were eligible for but were often misinformed about how much they were entitled to receive. In particular, we see widespread over-estimation of entitlements across all three programmes. At the same time, households’ reports of how much aid they received indicated that they were receiving less aid than their actual – and perceived – entitlement. This confirms our premise regarding information gaps in the context of such large-scale programmes – although the direction of the gap might be counterintuitive.

In November 2020, to counter these misconceptions, we provided personalised information on households' aid entitlements for each of these programmes through text messages, which were followed up by a phone call3. The endline survey was conducted between January and February 2021.

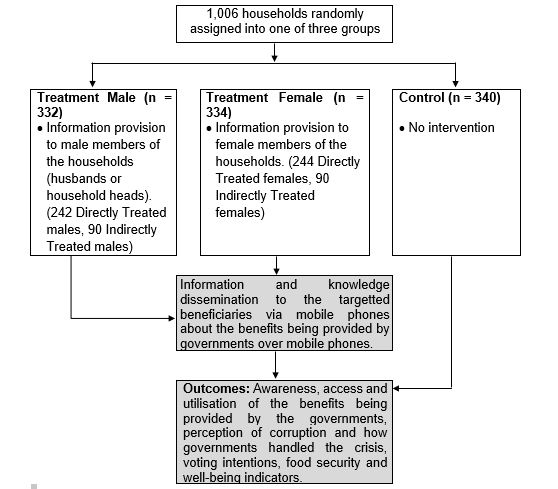

The research design involved a two-stage randomisation process with 1,006 households living in 60 slums. In the first step, we randomly allocated slums in equal proportion4 to one of three groups – either of two treatment groups, or a control group. In both treatment arms, we provided information on government benefits the household is entitled to. In one treatment arm, the information was provided to an adult male household member, while in the other arm, the information was provided to a female household member. Comparing the impacts in the two treatment arms allows us to test for the presence of gender-related frictions that may impede the flow of information within the household.

In the second step of the randomisation process5, we randomly selected 75% of sample households within the treated slums to directly receive the intervention. We refer to these households as being ‘directly treated’. The remaining 25% of sample households did not receive any contact from the research team, but could possibly receive information from the directly treated households within the same slum. Thus, they would have been ‘indirectly treated’. By studying intervention impacts on these indirectly exposed households, we can measure within-slum information spillovers.

Figure 1 summarises the experimental design.

Figure 1. Experimental design

Updating beliefs based on information provision

Recall that our baseline survey indicated that surveyed households consistently overestimated their entitlements across all three programmes. We find that after the intervention, treated households updated their beliefs regarding their entitlements from these programmes and lowered their perceived entitlement amounts6 to the actual entitlement amounts. By contrast, households in the control slums continued to overestimate their entitlements.

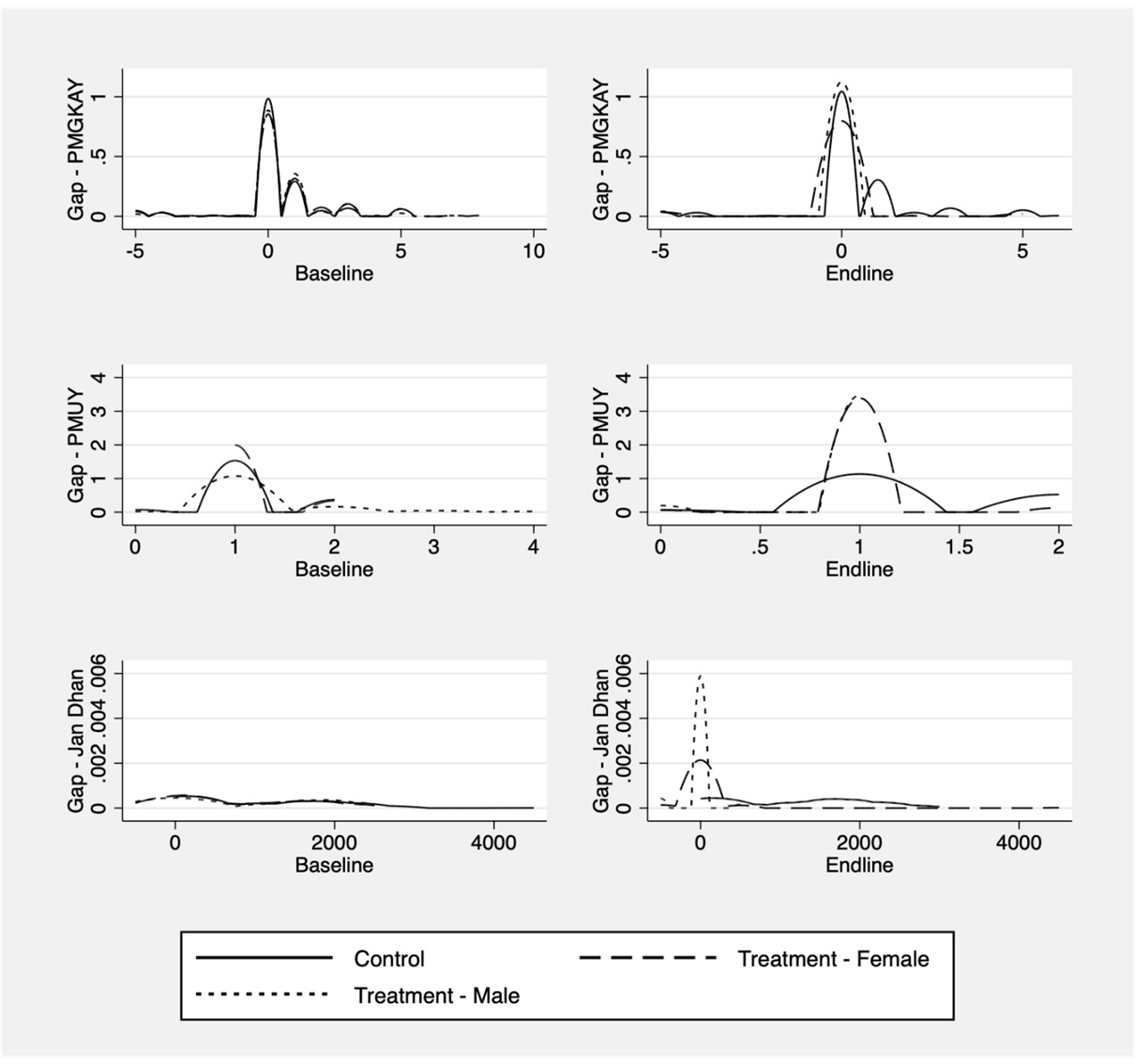

In Figure 2, we plot the distributions of the gap between how much each household believes it is entitled to versus how much it is actually entitled to7, for both the baseline and endline surveys. These distributions are plotted separately for the treated households in each treatment group and the control group and include only those households that reported knowledge of the existence of the programme8.

Figure 2. Gap in perceptions (in per-person/per-household terms)

Notes: (i) Figure plots distributions of the gap between what respondents believe they should receive from programme and actual entitlements for each of the three programmes. (ii) Figure only plots data for respondents who were aware of the programme. (iii) The units for the horizontal axes in each row are kg, LPG cylinders, and rupees, respectively. The gap is denoted on these axes, where 0 indicates no misperception. (iv) The vertical axes measure the density of responses at a given value on the horizontal axes.

Figure 2 clearly demonstrates a shift in the perceptions among treated households in the two treated arms, given that for these groups and for all programmes there are a larger number of observations centred around zero in the endline survey. In contrast, the distribution in the control areas closely resembles that at baseline, meaning that there was no updating of misperceptions over this time period in the absence of the intervention. Thus, this simple, low-cost, information-provision intervention improved the accuracy of households' beliefs, by shifting beliefs about entitlement amounts downwards.

In terms of the actual access to benefits, we find that directly treated households in treated slums receive around 6 kg more – on average – in foodgrains from PMGKAY and just over Rs. 100 more – on average – from JDY relative to control households in control slums. Thus, the intervention also increased access to benefits, even as it lowered expectations of entitlement amounts.

In the context of corruption and policy ineffectiveness, receiving this information from researchers at a reputed Indian university may have increased respondents’ confidence in the legitimacy of the information about the entitlements and their ability to obtain them. This changes the willingness of households to undertake efforts to obtain the benefits for which they are eligible, and explains the increase in benefit receipts when beliefs are revised downwards.

We also consider whether the intervention impacted households' food security, mental health, and life satisfaction. First, we find that the intervention reduced food insecurity. Moreover, we observe a simultaneous reduction in expenditures – for food and total expenditures – among the treated households. This suggests that these households substituted away from purchasing food from the market on account of higher receipt of food aid.

Turning to our measures of mental health and life satisfaction, we document significant improvements in the mental health, and financial and life satisfaction of respondents from treated households. In summary, having more accurate knowledge of benefit entitlements appears to have improved households' actual benefit receipts, thereby improving their food security and financial situation, in turn resulting in better mental health.

We do not find significant differences between the effects on households for which the male adult received the information relative to households for which the female adult received the information, suggesting relatively frictionless information sharing within the household on this issue.

We also find little evidence of information spillovers across households in the community, suggesting that the information was not widely shared outside the household. This is possibly due to the fact that the bulk of the information provided was tailored to each household's eligible entitlements, but could also be due to sparser social networks in urban settings9, combined with the fact that our sample included only a small percentage of households within the sampled slums.

Policy implications

Our findings are striking: first, we document that slum-dwellers in Kanpur systematically overestimated the amount of government benefits that they were entitled to. Second, we find that a simple, low-cost intervention (providing personalised information through text messages and phone calls) can substantially improve the accuracy of people’s beliefs regarding their entitlement amounts. Third, we find that, although residents’ beliefs about entitlement amounts were shifted downwards, their actual receipt of benefits went up. The greater access to benefits directly translated into lower food insecurity and better mental health.

Our work contributes to a growing literature on the effects of providing information on government benefit entitlements10. Our personalised information provision intervention provides some compelling findings which can inform emergency relief policy design. We demonstrate that low-cost but credible information interventions can have a substantial impact in such contexts11. In particular, providing such information can correct the target beneficiaries’ perceptions about benefit entitlements and change their behaviour, resulting in increased access to benefits. The similarity in the results across the gender treatment arms suggests that there is relatively frictionless information sharing within the household and that the success of the intervention is not dependent on which household member is provided the information.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Kanpur is the largest city in Uttar Pradesh and is home to one of the largest slum populations in the country (Sawhney 2016).

- Like PMGKY, this scheme was also announced on 26 March.

- This included information on the exact entitlement the household was eligible for, as determined from data provided at baseline, via text messages and follow-up voice calls.

- That is, a sample size of 20 slums in each of the three groups.

- We carry out a cluster randomised controlled trial using a randomised saturation design (as in Baird et al. 2018) to additionally measure information spillovers among households living in the same slum. Cluster randomised controlled trials with a randomised saturation design randomise not only the clusters that receive the interventions, but also the proportion of households within the cluster that receives the intervention. The latter thereby varies the intensity of the intervention within a cluster, allowing for the identification of within-cluster spillovers.

- In the case of Jan Dhan, they also lowered their beliefs on the number of household members eligible to receive aid from the programme.

- We evaluate this on a per-person or per-household basis, as per the scheme.

- For legibility, we do not show the distributions for the untreated households in treated slums, which largely follow those for the control group households.

- For more context on social networks in urban settings, see Banerjee et al. (2021).

- See Abramovskyet al. (2016), Carneiro et al.(2019) for studies on Colombia and Chile, respectively.

- There are several studies which find limited effects (see for example, Berg et al. (2021)). Also, the existing literature is focussed, for the most part, on providing health-related information (see, for example, Banerjee et al.(2020) and Islam et al. (2021)).

Further Reading

- Abramovsky, Laura, Orazio Attanasio, Kai Barron, Pedro Carneiro and George Stoye (2016), “Challenges to promoting social inclusion of the extreme poor: Evidence from a large-scale experiment in Colombia", Economia, 16(2): 89-141.

- Amirapu, A, I Clots-Figueras, B Malde, A Mitra, D Pakrashi and Z Wahhaj (2022), ‘Personalized Information Provision and the Take-Up of Emergency Government Benefits: Experimental Evidence from India’, Working paper. Available here.

- Baird, Sarah, J Aislinn Bohren, Craig McIntosh and Berk Ozler (2018), “Optimal Design of Experiments in the Presence of Interference", The Review of Economics and Statistics, 2018, 100(5): 844 – 860.

- Banerjee, A, E Breza, AG Chandrasekhar, E Duflo, MO Jackson and C Kinnan (2021), ‘Changes in Social Network Structure in Response to Exposure to Formal Credit Markets’, NBER Working Paper No. 28365.

- Banerjee, A, M Alsan, E Breza, A Chandrasekhar, A Chowdhury, E Duflo, P Goldsmith-Pinkham, BA Olken, B Golub and A Peter (2020), ‘Messages on Covid-19 prevention in India increased symptoms reporting and adherence to preventive behaviors among 25 million recipients with similar effects on non-recipient members of their communities’, NBER Working Paper No. 27456.

- Berg, Erlend, D Rajasekhar, and R Manjula (2022), “Pushing Welfare: Encouraging Awareness and Uptake of Social Benefits in South India”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(2): 901-939.

- Carneiro, Pedro, Emanuela Galasso and Rita Ginja (2019), “Tackling social exclusion: evidence from Chile”, The Economic Journal, 129(617): 172-208.

- Gentilini, Ugo et al. (2021), ‘Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: A real-time review of country measures’, Report, World Bank.

- Islam, Asad, Debayan Pakrashi, Michael Vlassopoulos, and Liang Choon Wang (2021), “Stigma and misconceptions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: A field experiment in India”, Social Science and Medicine, 278: 113966.

- Sawhney, Upinder (2016), “Slum Population In India: Extent And Policy Response”, International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 2(1): 2147-4478.

- Vyas, Mahesh (2020), “Impact of Lockdown on Labour in India", The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(S1), S73-S77.

01 June, 2022

01 June, 2022

By: Nakul 01 June, 2022

Excellent article! The hypothesis was interesting for a study in itself but more importantly, the subsequent article was written simply enough for a layperson (like myself) to follow. I also appreciated the length of the article which didn't go into too much depth so as to lose my interest.