Although India has emerged as a leader in digital labour market platforms, there is a dearth of data about the gig economy. Neha Arya describes the efforts taken by the CMIE to collect data on platform workers in the CPHS, and uses this dataset to describe the demographic composition of India’s gig and platform workers. She suggests that maintaining high quality data is necessary to ensure security and improve the quality of work for workers in this dynamic labour market.

Rapid technological developments are adding new dimensions to India’s employment generation challenge, leading to questions about the quality of work and nature of employer-employee relations. In recent years, the Covid-19 pandemic also provided fertile ground for the proliferation of different work arrangements, like remote or hybrid work. The Economic Survey of 2020-21 noted that India had emerged as a leading country for flexi-staffing or gig and platform workers. Simultaneously, India emerged as the largest supplier of online labour globally (ILO, 2021). In the post-pandemic period, a large portion of the pent-up consumer demand was channelised online – this meant an increase in the fleet of gig and platform workers, particularly in delivery, logistics, and personal services.

Consequently, there are now various discussions and debates about the impact of such work on the labour market. The Fairwork India report (2022) found that five of twelve platforms scored zero points on parameters examining conditions of work in the platform economy. Further, the introduction of the Code of Social Security (CoSS) 2020, aimed at extending social security to gig and platform (among other) workers, as well as the recent passing of the Rajasthan Platform Based Gig Workers (Registration & Welfare) Bill, reflect the increasing attention these new work arrangements are receiving. Therefore, in this article, I discuss the phenomenon of rising platform work in urban India and explore the characteristics of workers engaged in such work. Knowledge of the composition of the gig and platform economy could be essential for targeted policy action and prioritising the needs of platform workers.

Estimating the extent of gig and platform work

A digital platform acts as a mediator between service providers and service requesters, using software or mobile applications (Stewart and Stanford 2017). Globally, the number of platforms has grown swiftly, from 142 in 2010 to 777 in 2020 (ILO, 2021). However, owing to a lack of official national-level data on gig and platform workers, estimates of the magnitude of the gig/platform workforce in India vary by organisations. In 2022, using an indirect approach, a NITI Aayog report estimated that there were nearly 6.8 million gig workers in India in FY2019-20, comprising 1.3% of the workforce. This was expected to increase to 1.5% of the workforce in the following year. The majority of such workers were engaged in retail trade and sales, followed by transportation sector and manufacturing sector.

However, the report arrived at these estimates by using certain characteristics of gig worker (like urban location, age, education, ownership of mobile phones, among others) and then looking at occupations (using the National Classification of Occupations, 2004) and industries where it is known that demand for gig work exists. It then uses the Employment and Unemployment surveys of National Sample Survey (2011-12) and the Periodic Labour Force Survey (until 2019-20) datasets to estimate the total workforce, and then identifies workers with characteristics similar to those of gig workers. Therefore, these estimates remain close proxies of the size India’s gig workforce at best. Examining the employment potential of the gig economy, a report by Boston Consulting Group (2021) projected that the gig economy could comprise nearly 30% of India’s non-farm workforce in the long run. Moreover, it suggests that gig jobs are most likely to be present across sectors like construction, manufacturing, transportation and logistics, and personal services.

Capturing gig workers in survey data

To try and overcome the lack of availability of relevant data on gig economy, we approached the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and highlighted the need for collecting data on India’s platform workers in their periodic Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS). Accordingly, they introduced the codes “digital platform-based self-employed” and “digital platform-based salaried temporary” to capture platform-based workers. Data from three rounds of this survey is now available.

However, there are certain limitations of the dataset that need to be kept in mind when using it. To start with, urban platform-based workers from Karnataka make up an excessively large share of the sample (around 42.6% in the wave, when such workers were first captured). However, the sample was representative across demographic indicators – the distribution of platform workers by gender, age group, education, religion and caste was broadly similar to that of platform workers across the country. Although subsequent rounds of data collection witnessed some improvement in reporting gig work, it is likely that some measurement issues persisted due to investigators being unfamiliar with the new codes.

Another limitation arises due to divergence in the nature of the CPHS and the requirements for capturing platform work. Gig workers engaged in digital labour often tend to take up ‘gigs’ both online and offline. For example, a taxi driver working with a platform could also be taking rides offline in times of low online demand, or a smaller work allocation by the platform’s algorithm. But, unless most of the work is secured through an online platform, the worker would not be captured as a platform-based worker in the dataset. This would most likely lead to an underestimation of the urban platform workforce in India.

Key findings

With these limitations in mind, I discuss some of our key findings using the dataset in its current form. Since platform work is primarily an urban phenomenon, this analysis is restricted to urban areas (IWWAGE, 2020, NITI Aayog, 2022).

Table 1. Share of urban workers by employment category

|

Employment Category |

May-Aug 2022 |

Sep-Dec 2022 |

Jan-Apr 2023 |

|

Platform workers |

2.6% |

1.9% |

2.4% |

|

Daily wage/Casual labour |

18.7% |

18.1% |

18.1% |

|

Self-employed |

37.6% |

38.7% |

38.7% |

|

Salaried-Permanent |

25.9% |

25.9% |

25.2% |

|

Salaried-Temporary |

15.2% |

15.4% |

15.6% |

|

Total Urban Workers |

100% |

100% |

100% |

The CPHS data presented in Table 1 suggests that the share of self-employed individuals in the urban workforce is the largest, followed by that of regular wage workers. As a brief check, we compare this with employment shares by category of workers from the latest available round of the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) from 2021-22, which suggests that of the total urban workers, 39.5% were self-employed, 47.1% were regular wage/salaried (compared to ~41% suggested by the CPHS), and 13.4% were casual labourers. The reference periods and employment classifications of the two are not the same, but the distribution of workers by employment category seems to be broadly similar.

Presently, platform-based workers seem to make up only a small proportion of the urban workforce. Looking at the broad industry divisions, the majority of platform workers are concentrated in the trade and services industry (77%), followed by travel and tourism (12%). This is in consonance with the findings of the NITI Aayog report.

In terms of demographic characteristics, an overwhelming majority (96%) of platform-based workers are male. Even in advanced countries like the UK and US, women’s participation in platform work is lower than that of men (Farrell and Greig 2016, Balaram et al. 2017). In India, the skew appears to be comparatively much sharper, suggesting that the flexibility offered by platform work has not sufficed to attract enough women. This could also be on account of historically low female labour force participation rates in India, or the gender digital divide, or both. Among female platform workers, most were engaged in small businesses, tailoring and dress-making services, nursing and as other health workers, or in beauty services. On the other hand, men are mostly engaged in running small private businesses or transportation.

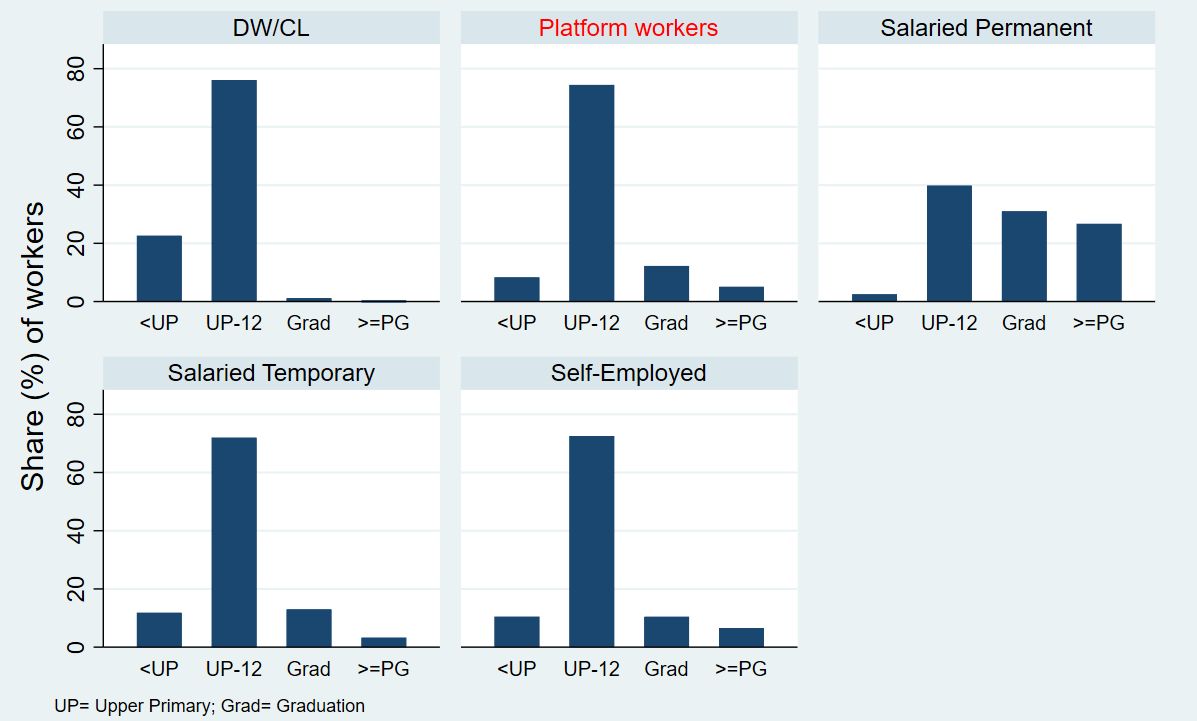

Over 80% of platform workers are married; Hindus; and work with their own establishment or vehicle. Moreover, nearly 75% had finished schooling, while some (~12%) also had graduate degrees (see Figure 1).

The high incidence of urban unemployment among educated persons above 15 years of age (9.5% as per PLFS 2021-22), could be a possible explanation for why workers with advanced degrees choose to participate in certain kinds of low-skill platform work. However, motivations of individuals for engaging in platform work is necessary for understanding this.

Figure 1. Distribution of workers across employment categories by level of education

Conclusion

The CMIE’s CPHS can fill an important gap in the data by capturing India’s platform workers. However, certain conditions need to be ensured for the data to be effective. First and foremost, a thorough understanding of what constitutes ‘platform work’ by field investigators as well as respondents is a pre-requisite for ensuring data quality. This is a crucial requirement, given the generic and ambiguous definition provided by the CoSS, where platform work refers to any work arrangement “outside of a traditional employer-employee relationship”. This could control for many transitions in and out of platform work observed across waves, as it becomes clearer which employment category a respondent belongs to. Surveys like those in the American Trends Panel in the US and Internet Use Survey in Canada, with periodic data on gig economy, have enabled understanding the scale, scope and reasons for people to undertake gig or platform work. This has facilitated various development measures to improve the working lives of gig and platform workers.

In India, Rajasthan’s new law for gig and platform workers may facilitate creation of a database of these workers in the state, while the national e-Shram portal can do the same at the country level. We can hope that labour statistics in India, led by the “Digital India” dream, are also able to reflect the realities of the dynamic labour market. This will go a long way in designing effective policy measures, especially for the expanding gig and platform economy in the country.

The author extends her sincere thanks to Professor Reetika Khera for her valuable suggestions and comments and to Mahesh Vyas (CMIE) for his support related to the CMIE dataset.

Further Reading

- International Labour Organization (2021), ‘World Employment and Social Outlook 2021: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work’, Report, ILO.

- Fairwork (2022), ‘Fairwork India Ratings 2022: Labour Standards in the Platform Economy’, Report.

- NITI Aayog (2022), ‘India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy: Perspectives and Recommendations on the Future of Work’, Report.

- Stewart, Andrew and Jim Stanford (2017), “Regulating work in the gig economy: What are the options?”, The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 28(3): 420-437.

- Balaram, B, J Warden and F Wallace-Stephens (2017), ‘Good gigs: A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy’, Report, Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, London.

- Farrell, D and F Greig (2016), ‘Paychecks, Paydays, and the Online Platform Economy Big Data on Income Volatility’, Report, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Institute.

- Periodic Labour Force Survey (2021-22), ‘Annual Report (July 2021 – June 2022)’, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

- IWWAGE (2020), ‘India’s Emerging Gig Economy: The Future of Work for Women Workers’, Report, The Asia Foundation.

27 September, 2023

27 September, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.