During 1994-1998, the state government of Haryana ran a conditional cash transfer programme to address the issue of child marriage: at the time of a daughter’s birth, parents from marginalised sections of society were promised a lumpsum cash transfer if the daughter remained unmarried until age 18. This article shows that the programme improved educational attainment and reduced child marriage but could not alter gender norms.

Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes that offer cash incentives if the beneficiaries satisfy certain conditions, have emerged as a widely adopted intervention to improve human capital and break the vicious cycle of poverty. One of the keys features of such programmes is the provision of a continuous frequency of payouts, which in many cases is yearly. Studies have raised concerns that the associated costs of complying can often be burdensome, especially in countries with weak institutions, often limiting their effectiveness (Brauw and Hoddinott 2011). On the contrary, programmes that depend on a one-time lumpsum payment at the end of a fixed term with limited conditionality can turn out to be effective in producing direct and indirect benefits for the recipients. In a recent study, we evaluate a programme that depended on such protracted cash benefits, the Apni Beti Apna Dhan (ABAD) programme, which was implemented in Haryana from 1994 to 1998 (Biswas and Das 2021).

Apni Beti Apna Dhan programme

Under the programme, parents who gave birth to daughters, were entitled to receive an immediate financial grant of Rs. 500 along with a long-term savings bond (with a maturity value of Rs. 25,000), which was redeemable only after the daughters turned 18 years, and if they remained unmarried. Households belonging to Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and those who possessed Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards, were eligible for being beneficiaries. We assess the long-term direct and indirect impact of the programme, that includes the likelihood of child marriage, educational attainment, and labour force participation of the potential beneficiaries apart from their time-allocation patterns, martial age, post-marital empowerment indicators, pregnancy-related indicators (for example, likelihood of institutional delivery, ante-natal check-ups), and intergenerational health indicators. We also examine how parents of the beneficiaries used such programmes in the marriage market to ensure for their daughters, grooms of higher social status such as those having a cemented house or large land parcels.

The study

We use multiple national- and state-representative datasets to evaluate programme effects. Our main data source is the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) conducted during 2015-16. We also utilise data from two rounds of the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) conducted in 2017-18 and 2018-19, along with the Time-Use Survey (TUS)1 conducted in 2019, to gauge the labour market and time-allocation effects of ABAD.

Since the ABAD programme spanned from 1994 to 1998, women who were in the age bracket of 16-21 years and were surveyed in 2015, and those in the age bracket of 17-22 years who were surveyed in 2016, are identified as women of eligible age (potential beneficiaries)2. The non-beneficiaries constitute our comparison group, including women in the older age cohort3 from Haryana and the neighbouring state of Punjab4, men in both similar and older age cohorts from Haryana and Punjab, and similar age cohort women from Punjab.

To estimate the programme impact, we use a triple difference methodology. Here, we first compare the age-eligible girls from Haryana with those who are older (first difference). We then compare this difference with similar difference between boys in Haryana (second difference). This comparison of boys and girls accounts for any difference between elder and younger girls that can emanate because of time effects. The second difference is then compared to the same second difference for Punjab (triple difference). This triple difference estimate gives the programme effect on potential beneficiaries of Haryana after accounting for the other confounding factors that can be linked to over-time improvements and also interventions other than ABAD that can influence the outcome indicator5,6.

The findings

Our analysis indicates a significant increase in education for the ABAD beneficiaries. The beneficiaries who were married were 7.6 and 6 percentage points more likely to complete secondary and higher secondary schooling, respectively. Nevertheless, we find no improvement in their labour force participation. We explore a number of factors that can explain this. First, the labour market returns to education may be non-linear and increasing, implying that individuals can take advantage of labour market opportunities only with the attainment of higher education. If ABAD had no additional impact on higher education attainment, job market benefits may have remained elusive. Our findings indicate that even though the likelihood of school completion increased, there was no further effect on higher education.

Second, because of the sticky gender norms historically prevalent in Haryana, female labour supply may have remained unaffected despite an increase in educational levels as women may not be allowed to go outside for work. If this was the case, time allocation in daily lives, among the beneficiaries, should also have remained largely unaffected despite improvements in education. Indeed, our results indicate no difference between beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries in terms of time allocated to domestic work, unpaid caregiving, socialising, practising self-care or spending leisure time7. Therefore, we argue that the norms and attitudes surrounding gender, despite the intervention, remained unchanged. This is also intuitive in the context of Haryana, where these norms are highly entrenched.

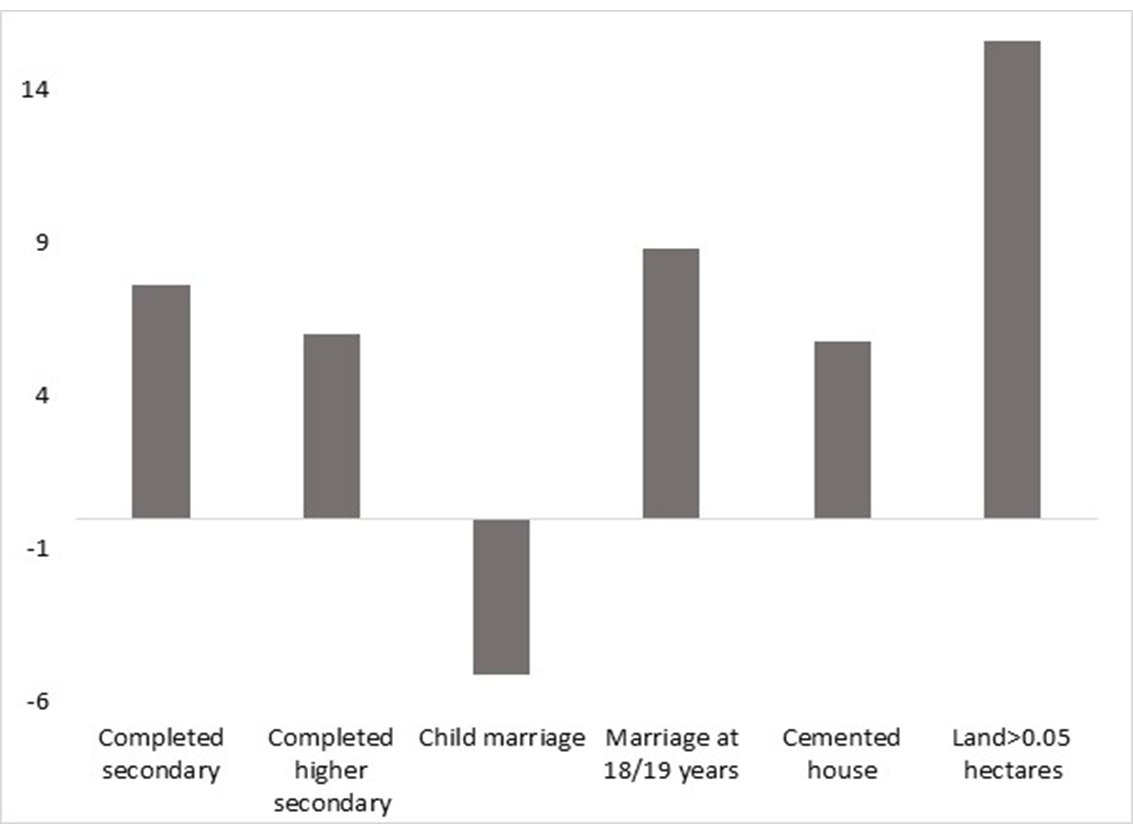

Figure 1. Effect of ABAD on selected outcomes

Note: The figure shows how much more likely the married ABAD beneficiaries are to complete a certain level of education, get married at a certain age, to belong to a marital household having assets like cemented houses or having land more than a threshold level – compared to non-beneficiary women in Haryana and Punjab.

Next, we assess the programme’s effect on age at marriage and post-marriage indicators among the beneficiaries. Our findings indicate a reduction in the likelihood of getting married before 18 years of age by 5.1 percentage points. This can be owed directly to the intervention as the cash incentive in the programme was linked to the girls remaining unmarried till 18 years of age. But what happened once the beneficiary received the money? We observe that the likelihood of getting married at 18-19 years increased by about 8.8 percentage points, implying that the ABAD programme did not substantively improve gender-centric norms. This is further highlighted by the fact that we find no changes in post-marriage empowerment indicators8; ante-natal and post-natal care, institutional delivery, duration of breastfeeding; and intergenerational outcomes like children being underweight, wasted or stunted.

Other marital returns

With the implementation of the ABAD, if the educational attainment of beneficiaries improved with no changes in their relative bargaining position after marriage or labour force participation, what then may have incentivised parents to invest in their daughter’s education? Our findings on the rise in marriage at 18-19 years complements those by Das and Nanda (2016) who document that ABAD receipts were being used as dowry in the marriage market. In contexts like Haryana, where early marriage and dowry were prevalent, it is possible that parents used dowry along with greater education of daughters to ensure better quality grooms and offset the cost of delayed marriage.

Here, our findings indicate that ABAD beneficiaries were more likely to get married in households with cemented houses and those with more than 0.05 hectares of land, often considered to be indictors of social status within a community. Further, we observe that ABAD beneficiaries who had completed secondary education were more likely to get married into such households. These pieces of evidence allow us to argue that parents may have utilised the ABAD transfers and improved their daughter’s education, to enhance their social status by marrying a better-quality groom.

Concluding remarks

Overall, we find evidence indicating that a CCT like ABAD that depended on the ‘promise’ of monetary benefits, was successful in increasing years of education among beneficiaries in addition to reducing the prevalence of child marriage. However, the programme failed to alter gender norms as indicated by an increase in the likelihood of marriage right after receiving the transfers, along with no improvements in labour force participation or other indicators of women empowerment. In fact, we observe that the programme transfers, and the associated educational gains were being used to secure grooms of higher social status. Our results underscore the need for complementary interventions that can alter societal norms and attitudes towards women, along with CCTs like ABAD, to derive optimal benefits.

I4I is on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- The TUS provides information about the time duration for which different activities are performed by the sampled population on the day prior to the survey.

- Henceforth, referred to as beneficiaries.

- Age group of 22-27 years and 23-28 years who were surveyed in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

- Haryana was carved out of the state of Punjab under the Punjab Reorganisation Act of 1966, indicating similar historical experiences shared by the residents of these two states. The Union Territory of Chandigarh is the joint capital of both Haryana and Punjab, and the two states have comparable sex ratios, literacy rates, and cropping patterns, making this a relevant comparison group.

- Using a similar strategy, we separate out the age-eligible individuals and comparison group for those surveyed in the PLFS and TUS. Our sample consists of individuals belonging to SC and OBC households.

- The results are robust to the inclusion of poor families based on BPL card ownership and wealth and per capita consumption expenditure percentile in our study.

- Time-use allocation change remained statistically insignificant for unmarried and married women, separately.

- The indicators include women’s ability to decide about her own health, large household purchases, visiting family, and the husband’s general attitude towards the wife such as asking whereabouts, accusing of being unfaithful, and limiting family visits.

Further Reading

- Biswas, S and U Das (2021), ‘What's the worth of a promise? Evaluating the longer-term indirect effects of a programme to reduce early marriage in India’, Global Development Institute Working Paper 2021-055, University of Manchester.

- Brauw, Alan de and John Hoddinott (2011), “Must Conditional Cash Transfer Programs be Conditioned to be Effective? The Impact of Conditioning Transfers on School Enrollment in Mexico”, Journal of Development Economics, 96(2): 359-370.

- Das, Priya and Priya Nanda (2016), ‘Are Conditional Cash Transfer Programs Gender Transformative?’, IMPACCT Policy Brief, International Center for Research on Women.

03 November, 2021

03 November, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.