Governments around the world are frenetically announcing an expanding slew of rapid response measures to address the fallouts of Covid-19 pandemic. The fiscal price tag on these measures is massive and growing rapidly. In this post, Datt and Bajaj argue for an alternative way of financing the fiscal response in India: the Reserve Bank of India could directly buy government bonds to the tune of the fiscal response, offering money to the government account, and then write it off.

The Covid-19 pandemic is both a major health and economic crisis. As country after country desperately tries to ‘flatten the curve’ of rising infections, the resulting disruption of economic activity is of a scale we have not witnessed in living memory. Synchronous recession in a large number of economies around the world is a foregone conclusion. Governments around the world are frenetically announcing an expanding slew of rapid response measures – augmenting resources for front-line first-response agencies in the health sector, providing immediate relief to afflicted populations whose lives and livelihoods have been disrupted, if not destroyed, and propping up as much of the economy as possible. The fiscal price tag on these measures is massive and growing rapidly.

There has already been some chatter about how this unprecedented fiscal response can be financed, whether it will lead to unsustainable fiscal deficits and government debt, and whether it will have to be financed through higher tax burdens in the future. The main argument of this piece is that none of these is an issue. This is because there is an alternative way of financing the fiscal response. The simple alternative mechanism is for the central bank to buy government debt equivalent to the size of the fiscal response, and then to write it off.

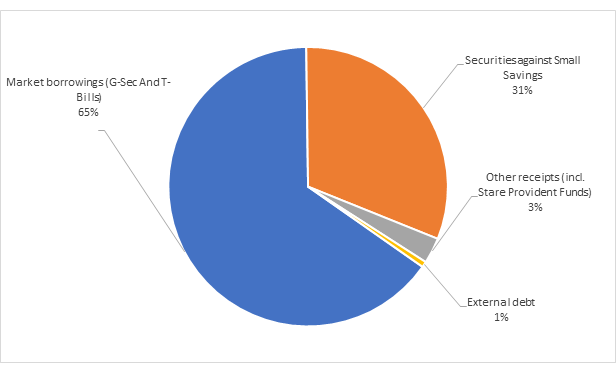

To explain the mechanism, note first how governments typically finance their fiscal deficits. As an illustration, the fiscal deficit of the Government of India (GoI) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2019-20 (as per the revised estimates) was Rs. 7.67 trillion, equivalent to 3.8% of GDP (gross domestic product). Figure 1 shows how this deficit was financed. About 65% of the deficit was financed by sale of government securities in the market (private sector), and another 31% was through issuance of government securities to the small savings fund (household sector). Though the relative share of market borrowings has generally been higher in earlier years, the key point is that nearly all of the fiscal deficit is financed by issuing government securities to the private or household sector.

Figure 1. Financing of GoI’s fiscal deficit: FY 2019-20

Source: Union Budget, 2020-21, Ministry of Finance, GoI

Note: G-Sec refers to government securities; T-bills refers to treasury bills.

With the looming recession, the appetite and the ability of the private sector for holding additional government securities could be limited1. Issuing government securities against the national small savings fund may be similarly compromised. However, there is an alternative mechanism. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) could directly buy government bonds (call them ‘Corona bonds’, if you like) to the tune of the fiscal response, offering money or more pertinently, crediting an equivalent amount to the government account. This will inflate government debt on the one hand and expand RBI’s balance sheet on the other. But this need be only temporary. Having thus monetised the additional government debt, the RBI could soon write off the government debt and shrink its balance sheet. There is also no need to finance the fiscal response through higher taxes in the future.

Such monetisation of government debt is an anathema to many economists. Of course, you do not want to resort to such a mechanism as the normal mode of operation, in the interest of preserving the independence of the central bank and to discourage unscrupulous government spending. The normal procedures for financing fiscal deficits exist for a reason. However, these are not normal times. Writing off government debt incurred in (and limited only to) the exceptional circumstances of supporting urgent relief effort is justified.

Is there a risk of inflation? If the RBI monetises government debt, this will certainly inject more liquidity into the economy. Whether it impacts inflation will depend on the supply response. There are reasons to believe that this risk is small. First, with the impending recession, the economy is well below its potential and may remain so for quite a while. Second, current levels of inflation are not high and will be further helped by low global oil prices. Third, if a good part of the fiscal response is specifically directed towards maintaining supply chains and facilitating firms (especially small and medium enterprises) to reopen without an overhang of unpaid debts, rents, and other obligations, which would otherwise put them out of business, it will go a long way to mitigate the risk of inflation. By playing this supportive role, government spending can in fact crowd in rather than crowd out private spending. We also note that maintaining supply chains is a priority in any case, irrespective of the size and mode of financing of the fiscal response, and should continue to be so. Fourth, the Covid-19-induced supply shock is already morphing into a demand shock as people’s livelihoods and incomes plummet, creating a deflationary overhang. A sizeable fiscal response can stem this tide without a major risk of fuelling inflation.

To conclude, no government, including GoI, should shy away from mounting the needed fiscal response to Covid-19 on grounds of limited fiscal space. The pragmatic though unorthodox alternative of the central bank monetising and then writing off government debt offers a way out.2 The problem of financing the fiscal response in our view is a complete red herring.

Notes:

1. In these uncertain times, the private sector will also be looking for a reasonable rate of return on government securities, which could put an upward pressure on interest rates.

2. As we write this, we note that a very similar argument has also just been made by Jordi Gali (‘Helicopter money: The time is now’). See chapter 6 in https://voxeu.org/system/files/epublication/COVIDEconomicCrisis.pdf.

12 April, 2020

12 April, 2020

By: Gaurav Datt 16 April, 2020

Yes, it is correct that our proposal implies that the realized equity component of RBI’s economic capital would be less than what it could have otherwise been (while the size of the RBI’s balance sheet does not change). But, we would not characterize this as “the government raids the RBI”. RBI’s risk buffers exist precisely for a “rainy day”, and we currently seem to be facing a downpour. Any shortfall in the risk buffers could be replenished through future surpluses of the RBI. As we caution in the note, this is not recommended as a normal course of business, but as a mechanism limited to the exceptional and urgent need for financing a rapid and substantial fiscal response to the Covid19 crisis. As for the risk of inflation, we already discuss this in the note and consider this risk to be limited for the reasons mentioned in the note. This is consistent with the Monetary Policy Committee’s recent assessment too: “Weaker overall demand outlook and lower crude oil prices should keep upside risks to inflation firmly contained, even in the face of temporary supply chain disruptions and scope for opportunistic use of pricing power. Arresting risks to the growth outlook and preserving financial stability should, accordingly, receive the highest priority…The need of the hour is to do whatever is necessary to shield the domestic economy from the pandemic.” (Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting March 24, 26 and 27, 2020).