In the fifth post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, Priyadarshini et al. leverage time use data from a study in Bihar, and find that girls take on a majority of domestic duties, and spend significantly less time studying or preparing for entrance exams. However, they note that since the pandemic, male participation in unpaid household work has increased. They also present qualitative evidence which shows that attitudes towards the conventional division of work are slowly changing among some youth.

Join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

Data from the first time use survey in India, released in 2019 before the outbreak of the pandemic, reiterates the acute time poverty faced by women and girls in the country (NSO, 2019). The data shows that women spend 19.5% of their average daily time on unpaid domestic and care work, while men spend only 2.5% of their time on such work. The available evidence suggests a clear association between time poverty, educational attainment and workforce participation for women and girls (see Nicholas 2016, Singh and Pattanaik 2019, and Chakraborty 2021). Low female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) of less than 20% in India (NSO, 2022) could also be seen as one of the manifestations of time poverty for women. The situation of women in states like Bihar (which has the lowest FLFPR (of just 6%) in the country) is even worse. In comparison to the Indian average of women spending 6.5 hours a day on unpaid domestic work, women in Bihar spend 8 hours on such work (NSO, 2019). As per a 2022 CMIE report, the unemployment rate for women in the 15-19 age group in Bihar was 76%. For the same age group, the national unemployment rate for women was 50%.

We show the association between time poverty girls’ education and work preparedness, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, in Bihar. Drawing from the time use data from a study (Ghosh and Priyadarshini, 2022) on the prevalence of early marriage in Bihar, we demonstrate the effect of the pandemic on time spent on education by young girls and boys. The mixed-method study was conducted between January and September 2021, right before and after the second wave of the pandemic, and was aimed at understanding the key triggers behind the prevalence of early marriage in Bihar. In total, 12,590 participants, comprising of married and unmarried girls (aged 14-25 years) and boys (aged 16-26 years); primary gatekeepers (fathers and mothers); and secondary gatekeepers (community leaders), participated in the study. Participants of the study represented 360 villages of 12 districts of Bihar, including six districts with high prevalence, three with medium prevalence, and three with low prevalence of child marriage.

We utilise socio-demographic information provided by the surveys and 48 questions from the Time Use tool, one of eight tools in the study. Half the items pertain to different time use activities and the remaining items capture whether time spent on the activity had increased, decreased, or remained the same since the Covid-19 pandemic. All participants were asked questions pertaining to perceived utility of education; belief, perceptions, norms and attitude towards early marriage; and tendency to control girls’ sexuality. Gatekeepers were additionally asked about their aspiration for children, tools for unmarried boys and girls included specific questions on accessibility to school; incentives of education or schools; and time use.

Gendered time-use patterns manifested in time-poverty for girls

Our findings show that girls were doing the majority of the domestic and care work (see Figure 1), while their ability to have a wider network, access to the job market (in the case of students, proxied by access to coaching classes, lack of time in preparing for examinations etc.) and exposure to media was reduced. Time spent on weaving, sewing or similar unpaid work for family was also higher among girls compared to boys.

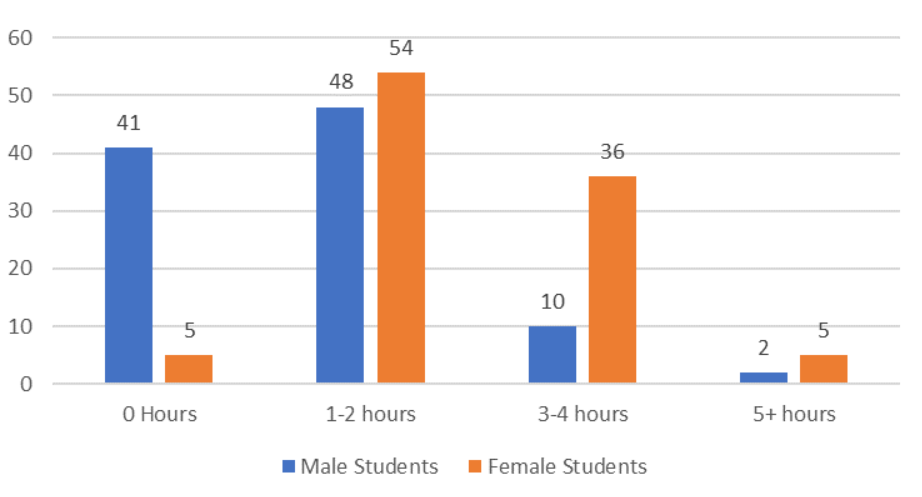

Figure 1. Reported time spent on domestic work, by percentage of total respondent

We found that about 41% of boys do not contribute to household work at all, and about 48% spend only 1-2 hours in such work. On the other hand, over 54% of girls spend at least 1-2 hours and 36% spend 3-4 hours on unpaid domestic work. Over 5% of girls spend more than five hours on such work. However, since the pandemic, male participants’ time spent on unpaid work such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare had increased at higher rates comparable to their female counterparts (see figure 2).

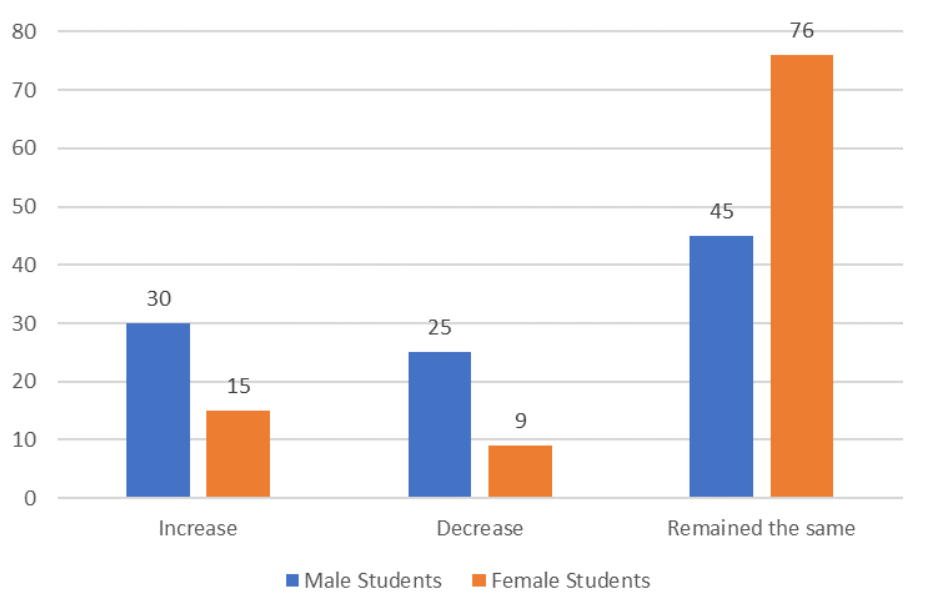

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents reporting changes in time spent on domestic work since the Covid-19 pandemic

More boys (30.36%) reported a rise in time spent on domestic work than girls (only 14.76%) since the Covid-19 pandemic. However, most youth participants (over 76% of girls and about 45% of boys) did not report change in the time they spend on domestic work since the pandemic. For most girls, time spend on unpaid domestic work either remained the same or had increased since the pandemic.

“For us lockdown made no difference, we are always in lockdown phase. We were always doing household work and during the lockdown there was more work.” – Girls from Begusarai

Time spent on educational preparation

We also found that time spent on preparing for entrance examinations for higher studies or jobs was substantially higher for unmarried boys compared to unmarried girls. In addition to attending online classes, screen time was also found to be higher among boys than girls.

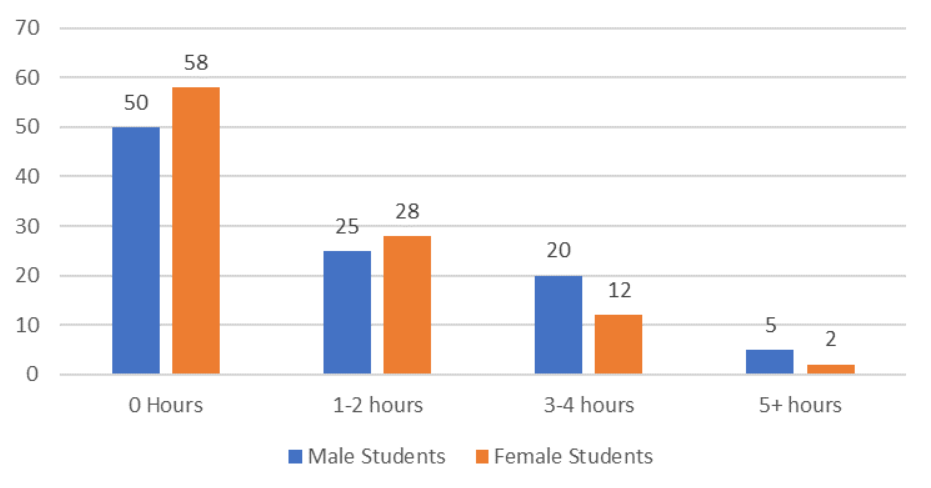

An important finding is that a large number of youth (49.79% of boys and 57.79% of girls) reported not spending even an hour on their educational preparation through self-study or preparation for entrance exams. Nonetheless, the gender gap was evident – in comparison to 20% of boys, only 12% of girls spend 3-4 hours on educational preparation see Figure 3). At 4.81%, the proportion of boys spending more than five hours on educational preparation was more than double that of girls (1.75%).

Figure 3. Time spent on educational preparation, by percentage of total respondents

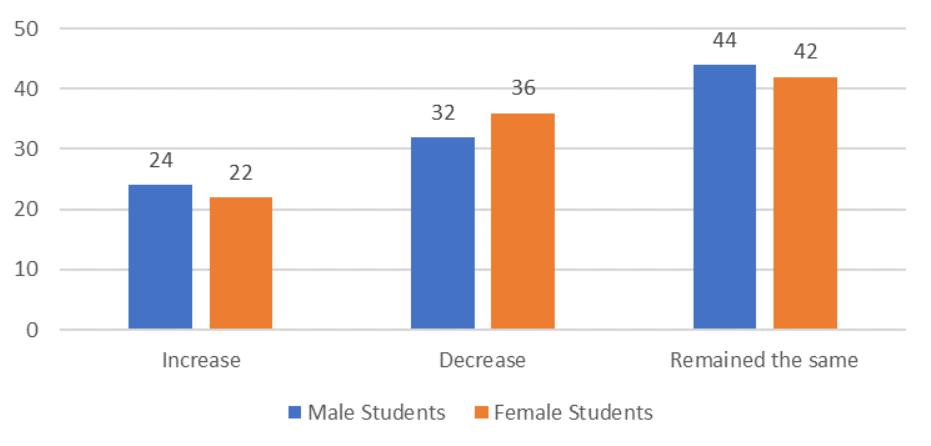

While a large share of boys and girls did not report any change in their time use on educational preparation, about 36% of girls and 32% of boys did report a decrease in time used for educational preparation since the pandemic. Over 24% of boys and about 22% of girls also reported an increase in their time-use for this purpose since the pandemic (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentage of respondents reporting changes in time spent on educational preparation since the pandemic

A significant correlation was observed between gendered patterns of time use, and the educational attainment of heads of households and households’ class and caste affiliation. Time spent on preparing for entrance examinations increased with when educational attainment of the household head was higher, irrespective of participants’ genders. Unlike participants from socially marginalised castes (SC/ST), participants from privileged castes (including OBCs and General Category) spend 3-4 hours on this activity. Participants from more developed villages and districts with low prevalence of early marriage also spend more hours on entrance examination preparation.

How have boys’ gender perceptions changed?

Qualitative data from the study reiterates that young females are overburdened with domestic chores. In two focus group discussions (FGDs), girls recognised domestic work as the responsibility of girls or women. In the other ten FGDs, girls expressed their discomfort with the burden of domestic and care-work, and noted that it affects their health. Additionally, they realised this burden was obstructing them from achieving their career aspirations. They also recognised that working for income was crucial for both men and women, as it would help them to utilise their education, contribute to the family income, and become independent.

“This is not right [men not sharing domestic workload] … that is why we are poor. Today both men and women need to earn and take care of the family. If both can work outside, both can work at home too. If it’s not happening, it should happen… women too have a body, how much work-burden they could bear… we have to work at home, take care of the children and there is so much to do… we don’t want to be poor like our parents. We want to work and earn a living. We want to have a job.” – Girls from Katihaar

In 10 out of 12 FGDs, boys reinforced the conventional division of work, envisioning women as homemakers and men as breadwinners. But some of them also argued that both men and women should share domestic workload and work for income...

“That is what our elders have decided. Husband should earn and wife should look after the family… she [a newly married bride] should stay at home [and not go outside for work or study]. People will criticise that his wife is going out… men should preserve the pride of family… my wife will stay at home and look after family, I will earn.” – Boys from Jehanabad

Some community leaders or secondary gatekeepers also realised that young women, especially married women, cannot spare time for studies due to household responsibilities. But none of the parents acknowledged that their daughters are spending more time on domestic chores and hence unable to spare time for studies or job preparation. Parents reported they are withdrawing their daughters from school or marrying them off early, mainly because of societal pressure and security concerns, but also because of daughters’ poor performance in school. The gender gap in aspiration for children was evident in their parents’ response. About 55-57% of parents shared they would like to educate their daughters only up to higher secondary, while 51-56% of parents would like to educate their sons to levels more than higher secondary, and even up to completion of a master’s degree.

“Yes, she [my daughter] went to school but failed twice in intermediate. Last year we couldn’t get her re-admitted because of lockdown… I had no plans about her marriage… but such was the fate. I found a good match... If she would have cleared her exams, I would have never married her off and have send her to college… also - it was a good proposal, so I didn’t refrain.” – A parent from Jehanabad.

Conclusion

As these findings show, young people’s time use patterns reinforce gender stereotypes, and the pandemic seems to have deepened the divide. The burden of unpaid domestic work is often manifested as time poverty for girls, who are not able to spend enough time on studies and preparation for entrance exams for higher studies/jobs. Perceived utility of girls’ education was also very low amongst parents. Higher educational attainment of household heads, households’ class and caste affiliation, and overall development level of the village are some of the factors contributing to bridging the gender gap in this regard.

We also find that attitudes toward domestic workload and gender relations are changing among some youth in rural Bihar, regardless of gender. Boys in two FGDs expressed comparatively more gender-equitable attitudes toward women earning an income. Most girls (in 10 out of 12 FGDs) reinforced the need to alleviate the domestic and care-work burden faced by girls and women. This also indicates an early internalisation of gender norms by both females and males, and that most girls are cognisant of the disproportionate burden of unpaid work that prevents them from engaging in activities required for strengthening their potential for better livelihoods. Nonlinear and complex time use patterns between time spent on household work and socio-demographic factors indicate that the highly patriarchal norms in rural Bihar are now shifting and being challenged.

“It [gendered division of domestic work] should change now, both men and women should be equal. If I am going out to work, then she should also go out. We see in the village that the bride is not allowed to go out than what is the use of her being educated? Husbands earn and they don’t help at home. But it should change – husband should help wife [especially] if he is going out to work for income.” – Boys from Motihari

Further Reading

- Chakraborty, Shiney (2020), “COVID-19 and Women Informal Sector Workers in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 55(35): 17-21.

- Chakraborty, S (2021), “Exploring time use and care Work: Why are so many women absent from the workforce in Bihar?”, Sakshamaa Briefing Paper, Centre for Catalyzing Change.

- Ghosh, S and Priyadarshini, A (2022), ‘Early marriage in Bihar: Drivers for changing attitude and reducing prevalence’, Sakshamaa Study, Centre for Catalyzing Change, forthcoming.

- National Statistical Office (2019), “Time Use Survey – 2019”, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Statistical Office (2022), “Periodic Labour Force Survey - Quarterly Bulletin, April-June, 2022”, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- Nichols, Carly E (2016), “Time Ni Hota Hai: Time poverty and food security in the Kumaon hills, India”, Gender, Place & Culture, 23(10): 1404-1419.

- Singh, Pushpendra and Falguni Pattanaik (2019), “Economic status of women in India: paradox of paid–unpaid work and poverty”, International Journal of Social Economics, 46(3): 410-428.

14 March, 2023

14 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.