In 2015, the central government launched District Mineral Foundations in the districts affected by mining, which are mandated to collect royalty from all mining activities and use the funds for the welfare of the local population. In this note, Banerjee and Ranjan give an account of how lack of political commitment and misplaced bureaucratic priorities have led to dismal planning and implementation of the programme in the mineral-rich state of Jharkhand.

Dhanbad – the coal capital of India – became a household name only after ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’, a two-part Bollywood movie on coal mafias, ruled the silver screen. Jharia near Dhanbad is home to India’s largest underground coal reserves and its underground fire has been burning for a hundred years. Yet nearly half a million residents surrounding this area suffer from acute water scarcity and chronic health ailments, and have meagre livelihoods. The story perhaps is the same across all mineral-rich districts in India, particularly across the tri-junction of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha.

Mining and related activities across India have had huge environmental and human costs, leading to loss of millions of hectares of forests and biodiversity. Thousands of people, including tribals, have been displaced and have found refuge as migrant labourers in India’s growing urban conglomerates. In spite of being critical factors in India’s shining growth story, most of India’s mineral-rich districts still live with some of the highest rates of poverty and inequality, with deplorable socioeconomic and human development conditions. It was to address this burgeoning inequality that the Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana (PMKKKY) was launched by the central government in 2015, to be implemented through funds under the District Mineral Foundation (DMF). The Mines and Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 (MMDR Act, 1957) was amended through the MMDR Amendment Act, 2015 to mandate provision for collection of royalty from all mining activities in mining-affected districts by the DMF trust, a non-profit body.

The establishment of DMF in 2015 laid hopes of a significant policy change towards addressing the long-term effects of mining through immediate focus on water supply, health, education, livelihoods and skill development of mining-affected communities through participatory planning including project approvals by gram sabhas1 in scheduled areas. However, a status report published in July by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) paints a bleak picture of DMF’s implementation across all the three major mining states, that is, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chattisgarh.

The model trust deed for DMF, provided by the central government, prescribed a two-tier administrative structure for the trust. The structure comprises a Governing Council (GC) of all the members of the trust, headed by the District Magistrate and a Managing Council (MC) to manage affairs of the trust. However, the composition of these committees is decided by state governments, leading to inappropriate domination of bureaucrats and local political representatives.

Lamp-black: Jharkhand’s anomalies

Since the launch of DMF in 2015-16, Jharkhand’s 12 mining districts have had an overall accrual of Rs. 27.32 billion as royalty collected from mining companies. Developmental works worth Rs. 17.43 billion have been sanctioned, of which an overall expenditure of Rs. 5.37 billion has been undertaken.

In West Singhbhum or Chaibasa as it’s known locally, six blocks are highly affected by iron ore mining covering nearly 31 panchayats (village councils) with approximately 65-67% tribal population and abysmal health and nutritional indicators. Yet, under total funds collected by the DMF trust in West Singhbhum, no significant amount has been allocated for health and nutritional services out of the district’s Rs. 1.68 billion sanctions. This is despite the fact that in the rural areas of the district infant mortality rate is 57 per 1,000, under-five mortality rate is 96 per 1,000, about 60% children below five years of age are malnourished, and nearly 73% of all women (15-49 years) are anaemic.

As per NITI Aayog’s latest data on nutrition, more than 45% of children below five years of age in Jharkhand are stunted; 29% are wasted ; and around 48% are underweight – all substantially above the country’s average. The major burden of this vulnerable population is borne by mining-affected districts of West Singhbum, Pakur, Godda, Bokaro, Ramgarh, and Dhanbad.

Figure 1. Health and nutrition dashboard

The untied nature of funds under DMF and mandated priority in health and nutrition by the DMF trust rules in Jharkhand could have been a golden opportunity for these high-burden districts to focus on the health and nutrition indicators of the mining-affected communities. However, lack of political commitment and misplaced bureaucratic priorities have led to dismal planning and implementation of the programme in Jharkhand. Contrary to the mandate under Jharkhand DMF Rules, no consultation with gram sabha and the affected communities is being conducted in mining-affected regions. Lack of participation of gram sabha or due cognizance of its decisions by Governing Council for drawing up annual action plans and planning necessary projects further demonstrates the lack of decentralised policymaking in this regard.

In addition to this, DMF trusts across all the 12 districts have ignored multiple guidelines of PMKKKY issued by the Ministry of Mines. Mandatory compliance of transparency by public disclosure of relevant information including list of beneficiaries and projects undertaken by each DMF trust on a dedicated website is yet to be operational.

The former Chief Secretary of Jharkhand conducted a meeting in October, 2016 with officials of all mining districts to review work and prioritise focus areas for projects to be undertaken by DMF trusts across the state. In that meeting, she directed all district magistrates, as chairmen of respective DMF trusts, to focus majorly on water supply and sanitation with an aim of making all districts ‘Open-defecation free’ (ODF). As a result of such a heavy-handed directive, DMF trusts in Jharkhand have ignored all other needs of affected communities and have been forced to provide additional funds for two major central and state government’s schemes related to water and sanitation. Out of the Rs. 17.43 billion sanctioned, more than 82% has been earmarked for water supply, about 15% to construct toilets, and a meagre 0.3 % for health and nutrition.

Table 1. Jharkhand's DMF funds

| Sectors | Sanctioned amount (in Rs. bn ) |

Percentage of total sanctions (%) | Expenditure (in Rs. bn) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking water | 14.33 | 82.2 | 2.892 |

| Sanitation | 2.74 | 15.7 | 2.332 |

| Health | 0.051 | 0.3 | 0.012 |

| Other (includes infrastructure and renovation works such as bridges, boundary walls, and training centres) | 0.315 | 1.8 | 0.142 |

| Total | 17.436 | 5.379 |

Source: Department of Industries, Mines and Geology, Jharkhand, April 2018.

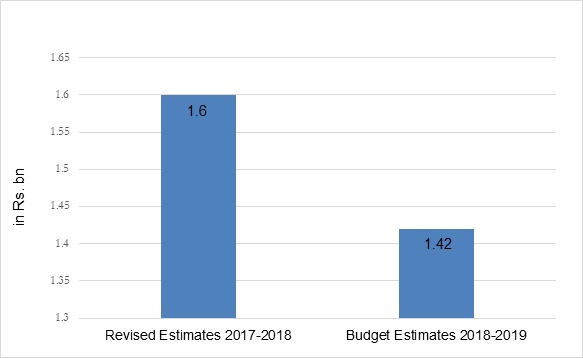

However a close scrutiny of the state budgets (2017-18 and 2018-19) of Jharkhand clearly shows that the allocation for construction of pipelines under rural piped water supply scheme has been reduced by more than 10%.

Are DMF funds supposed to solely make up for the budget deficit of the state government in these priority sectors? Although it is appreciable that clean water supply has been given importance, a blanket approach like this surely warrants deeper questions on the statutory requirements under the DMF Trust Act.

Figure 2. Rural piped water supply schemes under Jharkhand state budget

When the central government already boasts of its stupendous success under the Swachh Bharat Mission2(SBM) (rural), such forced allocation of money from a special fund to build toilets and make villages ODF should rather merit more scrutiny and questions regarding the efficacy of SBM implementation in these districts of Jharkhand.

In Dhanbad, not even a single rupee has been earmarked for Jharia, one of the worst-affected areas in the district. Even though Dhanbad falls under Critically Polluted Areas (CPA), there had been no spending on healthcare. Further, the piped water supply schemes in most of the districts covered under DMF, including Dhanbad and West Singhbhum, seem to concentrate only on basic water purification treatment and do not account for treatment of thick concentration of heavy metals/minerals (such as iron, mangnese, lead) dissolved in the groundwater.

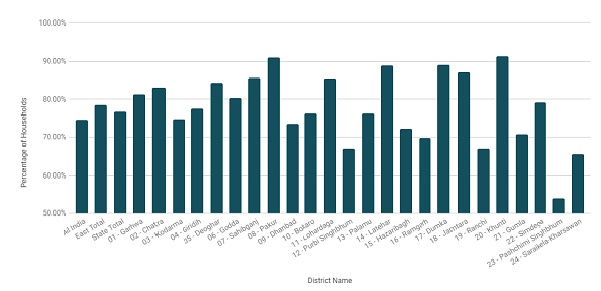

More than half of the working-age population in mining-affected districts like Dhanbad, Bokaro, Ramgarh, etc., are non-workers. In most of these districts, in over 2/3rd of households, the highest earning member’s salary is less than Rs. 5,000 per month, as per the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC), 2011. Yet, no district has planned a single project to address the issue of unemployment and sustainable livelihoods for the people living in mining-affected areas as well those who have been displaced and rehabilitated in other parts of the district.

Figure 3. Percentage of households where highest earning member earns less than Rs. 5,000 per month

With increasing global demand of iron ore and rich minerals from India, mining will continue in full thrust across India’s mining corridor. However policymakers and elected representatives should brace for devastating socioeconomic and environmental costs if appropriate steps for mitigation are no taken with immediate effect. In spite of tall promises, the DMF trust and PMKKKY scheme are gradually turning into yet another case of well-conceived government policy gone astray, driven by the usual top-down bureaucratic planning approach without adequate consultations with stakeholders to address the actual needs and lived realities in the mining-affected areas.

Notes:

- Gram sabhas a body consisting of all persons whose names are included in the electoral rolls for the Panchayat at the village level. According to the Constitution, gram sabha exercises such powers and performs such functions at the village level as the legislature of a state. For instance, they approve of the plans, programmes, and projects for social and economic development.

- India’s Swachh Bharat Mission began in 2014 with the ambitious goal of bringing widespread open defecation down from close to 70% of rural Indians to zero by 2019.

08 October, 2018

08 October, 2018

By: Dai software 20 April, 2021

This content is well-detailed and easy to understand. Thank you for creating a good content! on demand app development company