In October 2010, the government of Andhra Pradesh issued an emergency ordinance, bringing microfinance activities in the state to a complete halt and causing a nationwide shock to the liquidity of lenders, especially those with loans in the affected state. Using this massive dislocation in the microfinance market, this article identifies the “general equilibrium” impacts of a reduction in credit supply, which encompass changes to wages, employment, and consumption in the economy.

Microfinance is big business in India: in 2017, an estimated 40 million Indian households received 63 million microcredit loans from the approximately 223 microfinance institutions (MFIs) operating there (Ray 2017). Previous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in various contexts have focused on how borrowers stand to benefit from loans, either by investing in a household business (Banerjee et al. 2018, 2017) or accelerating consumption of durable goods such as buying a new roof (Ben-Yishay et al. 2017). While it is important to evaluate borrowers’ outcomes at the individual or household level, it is equally important to understand how the widespread availability of microcredit (approximately 20% of Indian households participate) affects the economy at a regional or even national level. These so-called “general equilibrium” impacts to the economy, which encompass changes to outcomes such as wages, employment, and consumption, are the focus of our research (Breza and Kinnan 2018).

Context: Andhra Pradesh’s ordinance

In October 2010, the state government of Andhra Pradesh (AP), India, issued an emergency ordinance, bringing microfinance activities in the state to a complete halt. The aim of the ordinance was to check the rising unrest in the state of AP after media reports of MFIs’ alleged coercive practices led to public outcry and backlash. The contraction in the supply of microcredit – caused by the ordinance – sent shockwaves far beyond AP. Affected MFIs could not collect on outstanding loans in AP, and larger lenders were reluctant to lend to MFIs, fearing similar actions by other states. Since the emergency ordinance came as a surprise, the microfinance crisis that followed serves as a natural experiment to measure the impacts of the loss of microfinance on rural households.

Our study

To focus on the effects of microloans per se, and not the other aspects of the AP ordinance (such as the de facto forgiveness of outstanding loans that households in AP had at the time of the ordinance), we look at households living in districts outside of AP. These households were affected indirectly, to the extent that the lenders operating in their districts were affected. Micro-lenders with a large presence in AP at the time of the ordinance experienced default on a large share of their total loan

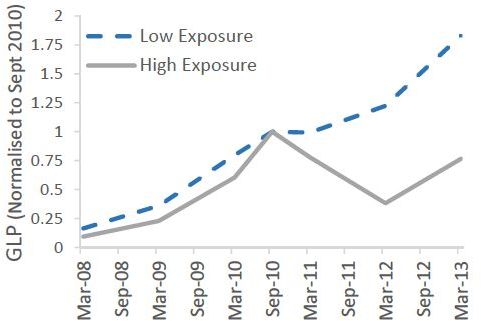

Figure 1 below shows how lending evolved over time. The dashed line shows lending by MFIs with low exposure to AP and the solid line shows lending by MFIs with high exposure to AP. Prior to October 2010, both groups of MFIs were experiencing similar rates of growth. After the ordinance was issued in October 2010, the lending patterns of the two groups diverged sharply. The low-exposure group continued to see growth in lending much as they did earlier, but the high-exposure group saw its lending fall sharply. This group of lenders did not begin to experience loan growth again until mid-2012. This is when the Reserve Bank of India assumed sole regulatory authority over the microcredit sector, resolving the risk of other states taking actions similar to that of AP.

Figure 1. Lending patterns of MFIs with high vs. low exposure to defaults in Andhra Pradesh

This figure shows the intuition for our research strategy. We are able to compare outcomes in two types of districts: those where the lenders operating there before the ordinance

RCTs and natural experiments

RCTs and natural experiments have different insights to contribute to the ongoing evaluation of microfinance’s impact

Results: Reduced rural wages and disproportionate impact of the poor

It turns out, the loss of credit had a measurable impact on the economy. The lower credit supply was associated with a 5–9% drop in rural wages. Because people had less money to spend, consumer spending, investment, and entrepreneurship also dropped. These effects were experienced by everyone in the economy, regardless of whether they had directly received microfinance. The results show that revoking credit can be very costly.

Another insight from the study is that some households were disproportionately affected by the sudden loss of access to credit. Households in the poorest fifth of the income distribution, who rely on casual labour for a large share of their income, were worst affected by the fall in wages. Intermediate-wealth households, who are often best positioned to use a microloan to expand their business, experienced the largest declines in consumption.

Concluding remarks

One could argue that the short-term losses due to a reduction in credit borrowed could be offset by future gains from not having to make repayments on these loans. However, we hypothesise that the present losses would lead to long-term volatility in wages, earnings, and consumption. Moreover, some effects of the credit crunch could persist, due to, for instance, durable investment or adjustment costs. Hence, the loss in total welfare resulting from a pronounced short-term consumption fall will not be fully offset by a future stream of slightly higher consumption.

Our results show that the actions of politicians in AP had large negative externalities on microcredit supply to the rest of the country. MFIs were no longer able to finance creditworthy borrowers in other states, which in turn led to decreased wages, earnings and consumption. This episode shows that microfinance, despite its small loan sizes, can have meaningful impacts on rural economies.

This article first appeared on VoxDev: https://voxdev.org/topic/finance/measuring-equilibrium-impacts-credit-evidence-indian-microfinance-crisis

Further Reading

- Banerjee, A, E Breza, E Duflo and C Kinnan (2018), ‘Do credit constraints limit entrepreneurship? Heterogeneity in the returns to microfinance’, Working paper.

- Banerjee, A, E Duflo and R Hornbeck (2017), ‘How much do existing borrowers value microfinance? Evidence from an experiment on building microcredit and insurance’, Working paper.

- Ben-Yishay, Ariel, Andrew Fraker, Raymond Guiteras, Giordano Palloni, Neil Buddy Shah, Stuart Shirrell and Paul Wang (2017), “Microcredit and willingness to pay for environmental quality: Evidence from a

randomised-controlled trial of finance for sanitation in rural Cambodia”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 86:121–140. - Breza, E and C Kinnan (2018), ‘Measuring the equilibrium impacts of credit: Evidence from the Indian microfinance crisis’, Working paper.

- Ray, A (2017), ‘Microfinance institutions are struggling for survival. Here’s why’, The Economic Times, 4 October 2017.

13 July, 2018

13 July, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.