Recent research has shown that schools often report overestimated learning outcomes, as they fear adverse consequences if they report poor performance. In this post, Gupta et al. describe a pilot study to measure reliability and validity of phone-based assessments, in which they tested students in Uttar Pradesh both over the phone and in person. They reveal that students performed similarly in both modes, and put forth some recommendations to state government looking to scale phone assessments and improve data reliability.

Debates on measuring student outcomes in India are usually about how much testing is appropriate for students, but often overlook whether student testing reflects actual student learning levels.

Recent evidence suggests that summative assessment data in the government school system is not trustworthy. Abhijeet Singh (2020) found that the student achievement levels according to a state-led census assessment were almost double that of retests by an independent third party in Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh. One possible explanation is that when this data is reported at the individual student level, students and parents care about them. When aggregated at different administrative units such as school, block, and district levels, teachers, block administrators, and district administrators respectively also start caring about it.

We can observe the same pattern in the case of the National Achievement Survey (NAS), which has high stakes for states at the national level. A recent study by Johnson and Parrado (2021) shows that state averages are significantly higher than the averages reported in the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) and the India Human Development Survey (IHDS). In short, summative data reported by schools and states indicate that students are on track, but researchers and independent third-party agencies are finding that learning outcomes in India have been overestimated.

The need for accurate learning outcomes data

This behaviour has a rich theoretical underpinning. The current set-up, in which schools are responsible for teaching, grading, tailoring instructions, and reporting, leads to a conflict of interest. Schools are held accountable for student learning, but schools are also the ones who report whether students are learning. Schools, fearing adverse consequences if they divulge poor performance, prefer to report good performance.

To what extent does not knowing the actual student learning levels affect students on a day-to-day basis? Take the example of the highly effective intervention, Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL), where teachers tailor their instructions based on student learning levels and not by their age or class. In such a programme, teachers will be misguided if assessment data do not inform them about the ‘right level’ of students’ learning. A recent study by Djaker et al. (2022) shows this to be the case – it found that teachers in India underestimate the extent to which their own students underperform in math and language. If these teachers implement TaRL in their classrooms, we may conclude that this programme doesn’t work, even though it was the input to the programme that ultimately led to its failure. Governments and aid agencies should exercise caution in promoting any similar data-driven reforms without due attention to the integrity of the underlying data itself. The quality of administrative data can place very high constraints on state capacity to target education policies effectively.

Until now, the cost of verifying learning outcomes reported by schools has been prohibitive, and this is where economical and promptly available phone-based assessments can fit in. Phones can help in reaching out to students directly in their homes. This way, states can bypass the administrative hierarchy of district, block, and school administrators, which could help ease these actors' conflicts of interest. However, reaching out to students’ homes also means that states should be careful not to make phone-based assessments high-stakes for individual students, because parents may start helping their children to answer questions.

Our findings

Before we go any further, it is critical to understand whether phone assessments differ from the regular assessments that happen in person.

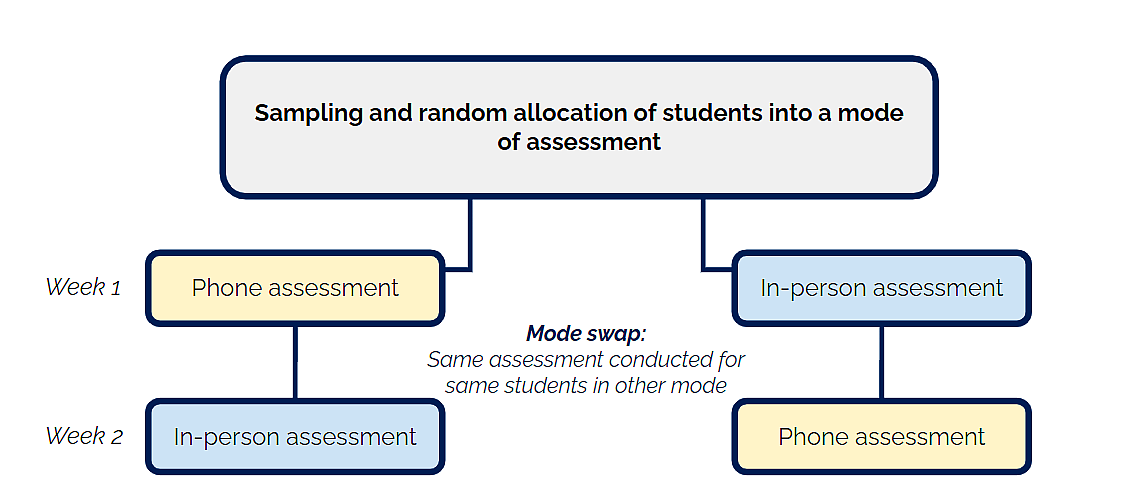

In a recent study (Gupta 2022), we aimed to establish the reliability and validity of phone assessments. We tested 449 government school students in Grade 2 and 3, in two districts of Lucknow and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. These students were tested in both modes – over the phone and in person – using the same assessment in mathematics and literacy using a crossover design, where students tested on the phone in the first period were tested in person in the second and vice versa (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Crossover research design

Many literacy questions (such as picture comprehension and reading fluency and comprehension) require visual aids, and so testing these skills using a phone could get tricky. We accomplished this by using school textbooks available at home, or sending images of questions from textbooks over WhatsApp if the family had a smartphone. For the corresponding in-person testing of students, the surveyors carried printouts of the same literacy questions.

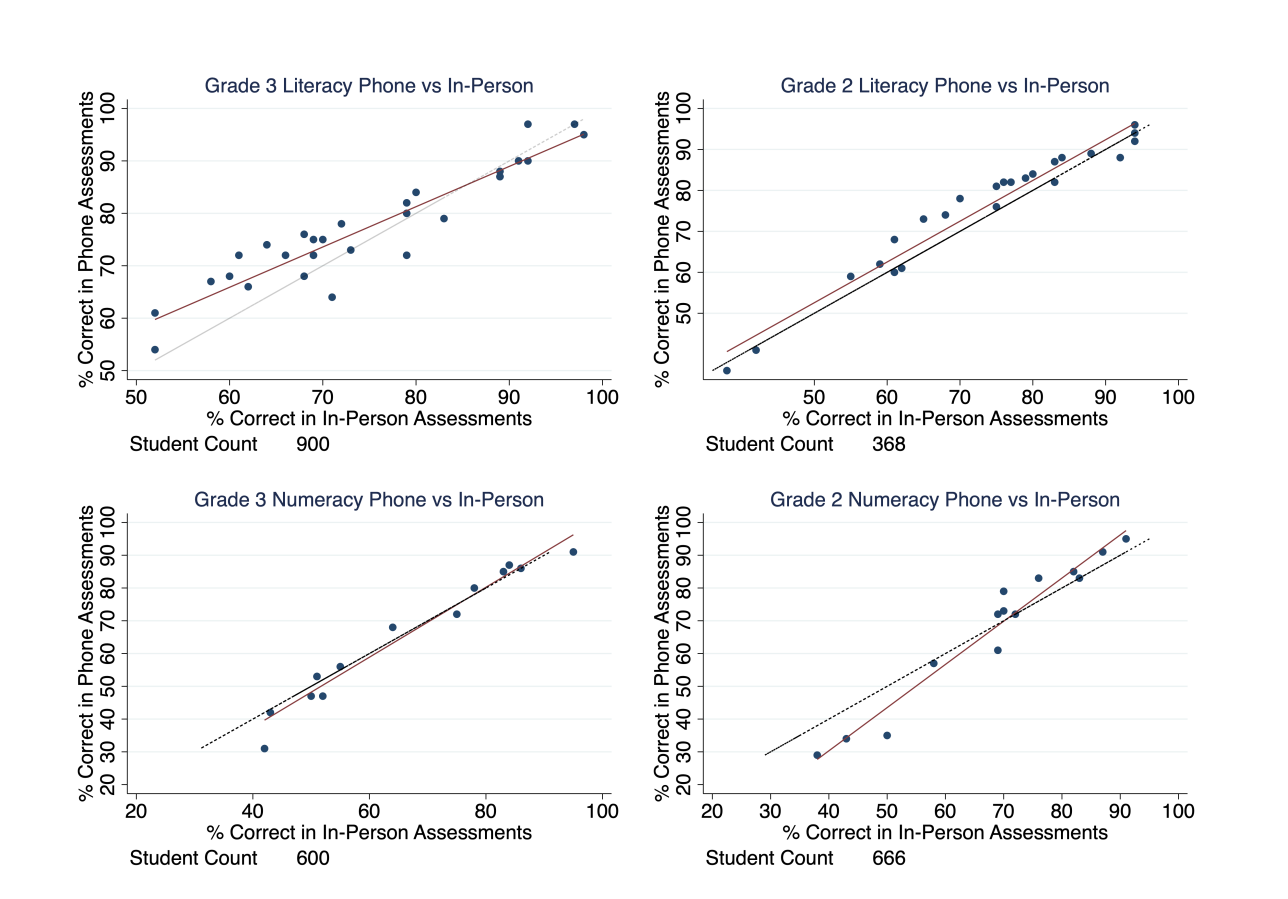

Through this small pilot, we found that phone assessments are psychometrically valid and reliable for measuring students' foundational literacy and numeracy skills (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Question performance over the phone and in-person

Notes: i) The y-axis represents the percentage of students who got questions correct on the phone, and the x-axis represents the percentage of students who got questions correct in person. ii) The 45 degree dotted line signifies that the overall performance on a given question is the same in both modes. iii) The red line represents the line of fit.

In all four graphs, the line of fit is very close to the 45 degree line. Put simply, performance on a given item is similar whether tested on the phone or in person. We also found that a given student performs similarly over the phone and in person, with a caveat that we found measurement errors in both modes. These results suggest that both modes are helpful when averaged across many students, but they can have a small margin of error for any individual student.

Effectively scaling phone-based assessments

This study shows promise, and the next step should be to evaluate whether governments can effectively integrate phone-based assessments as well. However, two concerns from this study should be tested when scaling and integrating.

First, our sample of students was more urban than the actual student population in these blocks. Our non-profit partner Rocket Learning provided us with the phone numbers of students, and at the time it mainly served urban students in the two districts. Governments can address this issue by mandating all schools to securely provide parents' phone numbers and store them in a repository.

The second concern is the possibility of distortion of data on the phone. Despite clear instructions from the surveyor, we observed that parents prompt answers to their children in both in-person and phone modes. However, prompting is 30 percentage points higher on the phone than in person surveyors cannot observe whispers and gestures on the phone easily, but can report if they have a suspicion of prompting. A video-based survey could help address some of these concerns, but the network connectivity in rural areas may not be strong enough to support that. In our estimates, prompting did not affect the outcomes, but at scale, governments should ensure that parents know that the students will not be rewarded or punished based on these scores.

The next logical step is to check if phone assessments can work at scale for primary school students, and if such assessments can improve the reliability of data reported by the school systems. To accomplish this, state governments can incentivise school systems by publicly recognising districts that report data reliably, after comparing them with parallel datasets generated by phone-based assessments. These parallel datasets need not be as large as the census assessments conducted by states; a sample assessment, like a household survey, should be sufficient.

Conclusion

Phone-based assessments are far more feasible today than ever before. The latest report by Deloitte (2022) suggests that India will have 1 billion smartphone users by 2026. United Nations projections estimate that India's population will be about 1.54 billion by 2026, and almost 65% of that population (that is, 1 billion people), will be aged 15-64, which overlaps with the majority of smartphone users’ ages as well. Even with conservative estimates, the projections favour almost universal household smartphone access within the next five to ten years. This increased access presents an opportunity for states to reach out to children through parents’ smartphones to assess their learning levels, without worrying about accessibility in remote areas.

Phone assessments could prove to be far more economical than third-party assessments such as ASER. They can be conducted more frequently, and provide district administrators and teachers with timely information. Call center infrastructure already exists in many states. Taking these considerations into account, state governments should consider exploring phone-based assessments to potentially improve data quality and usher in a culture of honest reporting.

Further Reading

-

Deloitte (2022), ‘Technology, Media, and Telecommunications - Predictions 2022’.

-

Djaker, S, AJ Ganimian and S Sabarwal (2022), ‘Primary- and middle-school teachers in South Asia overestimate the performance of their students’, Working Paper.

-

Gupta, S, K Satyam, N Gupta and R Ahluwalia (2022), ‘Can Phone Assessments Generate Reliable Student Learning Data?’, Central Square Foundation, 22 November.

-

Johnson, Doug and Andres Parrado (2021), “Assessing the assessments: Taking stock of learning outcomes data in India”, International Journal of Educational Development, 84.

-

Singh, A (2020), ‘Myths of Official Measurement: Auditing and Improving Administrative Data in Developing Countries’, RISE Working Paper 20/042.

11 January, 2023

11 January, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.