Right to Education Act, 2009, was designed to provide the right to free, quality school education to all 6-14 year olds in India. This article examines the influence of RTE on the expansion of private tutoring. It finds that the Act led to a significant increase in the number of private tuition centres that necessarily help the relatively well-off students who can afford them, thereby counteracting the goal of equitable access to schooling.

While the highest quality Indian schools and universities produce world-class scholars, innovators, and entrepreneurs, a significant portion of the population still cannot compete in global labour markets. India’s Right to Education Act (RTE) – passed in 2009, and implemented across the nation in subsequent years – was designed to address the important underlying issue of providing access to quality education to all 6-14 year olds in the country. Whether it has been able to achieve its objectives will remain an important question in India’s post-pandemic educational and human capital policies, going forward.

The promise of RTE was to expand the nation’s human capital while simultaneously delivering more equitable outcomes. By ensuring that all students could attend primary schools, the nation moved vigorously to help those left out of previous development.

Unfortunately, the outcomes of RTE illustrate how individual reactions to governmental programmes can subvert the intent of a programme. In recent research, we look at the causal influence of RTE on the expansion of private tutoring (Chatterjee et al. 2020). We find that universalising access to schools led to a significant expansion of private tutoring, which necessarily helps more advantaged students compared to those from low-income families. Thus, the move toward more equitable access to schools was counteracted by the expansion of tuition centres.

India’s Right to Education Act

In 2000, only 86% of Indian children were in primary schools, and the survival rate to grade 5 was 47% (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2003), underscoring India’s longstanding challenge of providing broad access to schooling. With the worldwide push for expanded school access, India began moving toward universal access, and passed the RTE following a complicated path. In 2002, the 86th amendment to the Constitution introduced Article 21(a), which stated that “the State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine.” The RTE was first presented to the parliament in 2006, but it was rejected and lack of funds was cited as the official reason. However, the RTE was approved by the Union Cabinet in 2008 and then passed through both the houses of the Parliament by August 2009, making it a national law. By 2012, all the state governments implemented the RTE by passing it in their own state legislatures.

RTE ensures that every child in the age group 6-14 years has the right to admission in a quality neighbourhood school, but does not mandate that a child must access only neighbourhood schools. Further, RTE mandates that any private unaided schools in the neighbourhood must allocate 25% of their entry-level seats (grade 1) to economically weaker sections and disadvantaged groups, and the compensation for the costs incurred by the private schools would come from the government. RTE mandates that all schools offering primary and upper-primary education must have good infrastructure in terms of a weather-proof building, boys’ and girls’ toilets, drinking water, ramps for the handicapped, a library, and so on. It also specified quality indicators for teacher preparation, class size, and the like.

Interestingly, however, the debate about RTE never considered that RTE might induce an expansion of private tutoring, and that this could offset the equity improvements from increased access to schooling.

Tuition centres

Private tutoring is widely consumed around the world, but there are few analyses of the extent and character of such education (Bray 2017). Opinions on the impact of tuition centres tend to differ across countries – ranging from a useful complement to government schools to a source of inequity in society. The net impact on welfare is difficult to ascertain from existing literature.

In India, there has been a tradition of private tutoring since the 1980s (Azam 2016) with a recent report stating that parents in India lack trust in government schools and spend as much as 35% of household income on private schooling and supplemental education. A primary motivation for private tutoring that is frequently cited by Indian households is improving performance on key exams that determine schooling options, and access to quality post-secondary schools.

RTE’s impact on private tutoring

Our research considers the offsetting effects to equity improvements of RTE arising from induced expansion of private tutoring. We develop a unique database of registrations of new private educational institutions offering tutorial services, by local district, during 2001-2015. We estimate the causal impact of RTE on the expansion of private supplemental education by comparing the growth of these private tutorial institutions in districts identified a priori as having very competitive educational markets to those that had less competitive educational markets.

The key to our identification of the causal effect of RTE on private tutoring is comparing changes in private tutoring after passage of RTE for groups with intense educational competition and groups with less competitive pressures. Our main analysis leverages this intuition, and defines highly competitive districts as those containing one of the premier technical schools – an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT). The location and governance of the original IITs were exogenously set in 1961 as per the IIT Act. The admissions competition for these undergraduate schools is especially intense as they have been traditionally viewed as a clear gateway to economic success in India. The comparison less-competitive districts are those lacking one of these institutions. While students from throughout India can attend any given IIT, the importance and competition clearly rises in the local district.

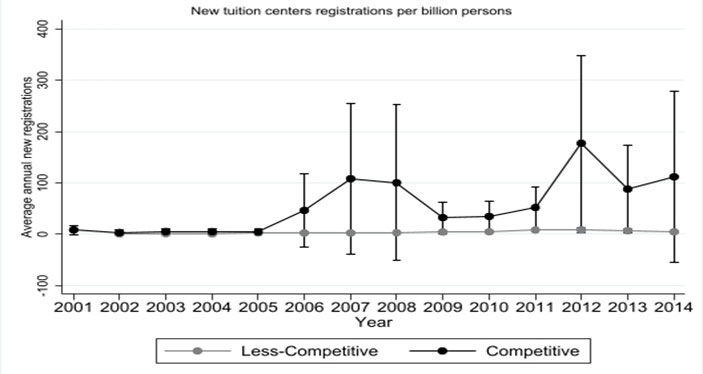

The intuition behind our ‘difference-in-differences’ approach is that, if the educationally competitive and the less-competitive districts are following common trends in the development of tuition centres before RTE, those trends would continue in the absence of RTE. Deviations from trend after the introduction of RTE are interpreted as the causal effect of RTE on private tutoring. In the empirical analysis, we verify and validate this parallel trend assumption.

Figure 1 provides a visual display of the expansion of tuition centres between 2001 and 2015. The monthly registrations are flat until just before the final enactment of RTE, but thereafter show some increase with the anticipation of RTE, and a strong jump after enactment in the educationally competitive districts.

Figure 1. Parallel trends of new tuition centre registrations, per billion persons

Overall, we find a strong causal impact of RTE on the private tutoring market. Our baseline findings show that, with the expansion of school access due to RTE, the number of private tutoring centres in India expanded at a monthly rate of 53 per billion people in our educationally competitive districts. For the post-RTE period through 2015, this implies a conservative, estimated expansion of about 172,000 tuition students in the 14 IIT districts. While India has a wide range of tertiary schools, the IITs actually have just 10% of this number of new tutoring students enrolled in them.

Conclusions

Tuition centres may facilitate human capital generation either at the remedial or competition/excellence margin, but our results also show that, while the intent of education for all is noble, private behaviour can offset the equity enhancement implied by the expanded access. The issue is highlighted by the pre-RTE observation about the rise in shadow education in India of Amartya Sen (2009): “Underlying this rise is not only some increase in incomes and the affordability of having private tuition, but also an intensification of the general conviction among the parents that private tuition is “unavoidable” if it can be at all afforded (78 per cent of the parents now believe it is indeed “unavoidable” – up from 62 per cent). For those who do not have arrangements for private tuition, 54 per cent indicate that they do not go for it mainly or only because they cannot afford the costs.” The RTE compounded this problem.

The active neglect of the issue of tuition centres by Indian policymakers and administrators has recently also incentivised the rise of digital education firms in India, such as Byju’s. These firms induce private behaviour by offering personalised services (such as dedicated mentor, one-to-one tutoring, etc.). They also charge different prices for varying levels of personalised services (like freemium model1) to increase its coverage and strengthen its market position. In addition, these new digital education firms may contribute to legitimisation of current practices of shadow education where students are taught strategies to score higher in competitive exams like JEE (Joint Entrance Examinations) for IIT entrance, and NEET (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test) for entrance into medical courses. Finally, the rise of in-person and online tuition services only weakens the role of teachers since students may choose to reserve their attention and effort for tuition classes and not towards teachers during school hours. In essence, the rise of digital tutoring firms like Byju’s threatens the purpose and existence of formal education itself, further deepening the adverse welfare implications of our findings in terms of equity and educational outcomes of India’s millions with RTE (for example, Jha et al. 2019).

While it is beyond our basic analysis of RTE, policymakers should consider these implications, building especially on the recently approved 2020 National Educational Policy of India. The answers are quite clear to us. High-quality education must be provided to all. It is not sufficient to mandate universal access without continuous monitoring of the quality of the delivery of education in the ecosystem. This needs to happen both for the brick-and-mortar shadow education startups in India, and their more recent digital siblings.

A version of this article has been published on VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/unintended-consequences-education-all-india-s-right-education-act

Notes:

- Freemium is ‘a pricing strategy by which a product or service is provided free of charge, but money is charged for additional features and services.’

Further Reading

- Azam, Mehtabul (2016), "Private Tutoring: Evidence from India." Review of Development Economics, 20(4):739-761.

- Bray, Mark (2017), "Schooling and Its Supplements: Changing Global Patterns and Implications for Comparative Education", Comparative Education Review, 61(3):469-491.

- Chatterjee, C, EA Hanushek and S Mahendiran (2020), 'Can Greater Access to Education Be Inequitable? New Evidence from India’s Right to Education Act', National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 27377, Cambridge, MA.

- Jha, J, N Ghatak, P Minni, S Rajagopal and S Mahendiran (2019), Open and Distance Learning in Secondary School Education in India: Potentials and Limitations, Taylor & Francis.

- Sen, A (2009), 'Introduction: Primary schooling in West Bengal', in Pratichi Research Team (eds.), The Pratichi Education Report II - Primary Education in West Bengal: Changes and Challenges, Pratichi (India) Trust, Delhi.

- UNESCO (2003), 'Global Education Digest, 2003: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World', UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Montreal.

10 August, 2020

10 August, 2020

By: Kaushik Choudhary 14 August, 2022

I am thankful for your efforts in highlighting the fact that quality education is not available for poor and underprivileged. Quality education has been turned into a comodity that brought and sold . Those who are already well off can afford these private coaching and tutors. Being from a somewhat poor family had made access to quality education difficult and sometimes impossible.