Despite the expansion of free healthcare for the poor throughout India, many hospitals continue to charge patients out-of-pocket fees. In this study, Dupas and Jain investigate whether informing patients of their benefits helps hold hospitals accountable. They survey dialysis patients in Rajasthan entitled to insurance under a government scheme and find the impact of the information intervention manifests differently in private and public hospitals, with a decrease in out-of-pocket payments only in the latter, driven by a reduction in payment for tests and medicines.

Healthcare is a major expense for low-income families around the globe, and these costs play a significant role in exacerbating poverty. The World Health Organization estimates that out-of-pocket healthcare costs push 100 million people into extreme poverty every year (WHO, 2022). The burden of health-related expenses is exceptionally high in India, where almost 20% of households experience ‘‘catastrophic” health expenditures in a given year.

Policymakers in India and many other countries have expanded the provision of public health insurance to address this problem. However, many hospitals continue to charge out-of-pocket fees to patients and many beneficiaries of the programmes are not aware of the benefits to which they are entitled. Can ‘bottom-up’ accountability – where patients are informed of their entitlements and can push back on fees or change healthcare providers – help hold hospitals accountable?

In our study (Dupas and Jain 2023), we examine the role of hospital compliance in the effectiveness of government health insurance in Rajasthan. We surveyed patients from private and public hospitals to measure their awareness of their benefits, and also evaluated whether providing patients with information enables them to hold hospitals accountable and obtain their full benefits.

Persistence of out-of-pocket payments

Government-financed health insurance has been a key policy tool to expand healthcare access and reduce health-related financial risks in lower-income countries (Bukhman et al. 2020). Indian central and state governments have rapidly scaled up public health insurance that provides free hospital care to poor households since 2008, and by 2021, the national budget on government health insurance was Rs. 6,400 crore ($1 billion) (Shukla and Kapur 2022).

Despite these measures, out-of-pocket health spending has remained stubbornly high in India, and even increased in many countries. Evaluations of public health insurance programmes around the world find positive effects on healthcare access but mixed effects on out-of-pocket payments (Giedion et al. 2013). In India, numerous studies find that households continue to spend large amounts on healthcare despite insurance coverage (Rao et al. 2012, Karan et al. 2017, Nandi et al. 2017, Sriram and Khan 2020, Malani et al. 2021). Ensuring that insurance meets its goal of increasing financial protection requires us to understand the causes of these costs and identify scalable solutions.

One explanation for the persistence of these costs may be low awareness of insurance benefits among patients (Barik et al. 2020). This may allow hospitals to contravene programme rules and charge patients for services that should be free. Increasing ‘bottom-up’ accountability by informing and empowering the intended beneficiaries is often advocated as a way of reducing leakage in public programmes and ensuring that citizens receive their full entitlements (World Bank, 2003). Accountability measures may help patients exercise their ‘voice’ and claim their benefits from providers, and/or exercise choice and ‘exit’ to other providers that better meet their needs (Hirschman 1972, Devarajan and Reinikka 2004). However, whether such efforts are actually effective depends on the programme’s context.

Can information increase bottom-up accountability and lower costs to patients?

Our research was conducted in the context of the Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana (BSBY), a large, state-run public health insurance programme that entitles 46 million individuals in Rajasthan to free care at public and certain private hospitals.

We studied the role of hospital compliance in the effectiveness of government health insurance. We used survey data and conducted a randomised evaluation of an information intervention to test whether phone-based information about programme benefits can enable insurance beneficiaries to hold hospitals accountable and lower costs to patients.

The study was conducted among patients requiring dialysis treatment for chronic kidney disease.1 We surveyed 1,113 dialysis patients from 91 hospitals (70 private and 21 public) that accept the public health insurance program. The surveys were done by phone and used to collect data on their awareness of BSBY entitlements, care-seeking, and out-of-pocket payments over the previous month.

At the end of the survey, patients (or the relative in charge of their care) received the information over the phone. They were told that they were entitled to free care under insurance, how much the government pays hospitals to provide free dialysis, and the names of up to three other participating hospitals within 10 kilometres of their hospital. This content was designed to strengthen the two channels of accountability mentioned earlier: ‘voice’ (bargaining with their hospital to reduce their payment) and ‘exit’ (switching to a different public or non-BSBY hospital).

We staggered the rollout of the survey and information, enabling us to compare outcomes among treated individuals with those yet to be treated, as well as their behaviour before and after the intervention. We measured impacts with a follow up survey 7-8 weeks after they received the information. We looked at average effects, as well as effects on public hospitals and private hospitals accepting BSBY.

Key findings

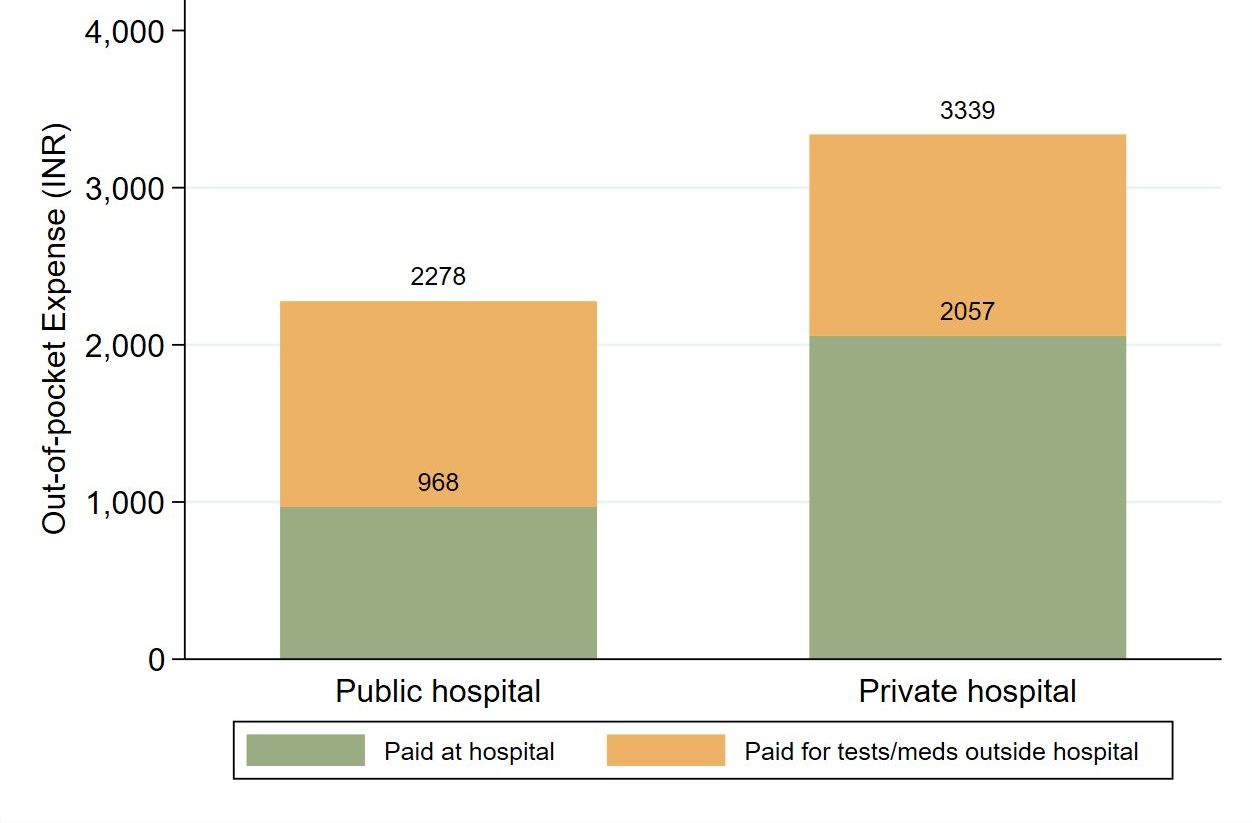

We found that awareness of benefits is low, and participating hospitals often charge unauthorised fees to poor patients eligible to receive free care. Average out-of-pocket payments for chronic kidney care patients, shown in Figure 1, are approximately Rs. 3,000 per month (the equivalent of $43, or 25% of India’s annual GDP per capita). Costs at both public (Rs. 2,300) and private (Rs. 3,300) hospitals are high, and tests and medicines that patients have to obtain outside the hospital account for 45% of the total expense on average (and 60% at public hospitals). Awareness of programme benefits is low despite patients having used insurance for several months.

Figure 1. Out-of-pocket payments at baseline

Notes: i) The figure presents the average out-of-pocket expenditure that patients at public and private hospitals paid for their dialysis treatment in the month before the survey (at baseline), before we conducted the experiment. ii) Total payments are split into the amount paid directly to the BSBY hospital and the additional amount paid for tests and medicines that patients had to obtain outside the hospital for the same visits.

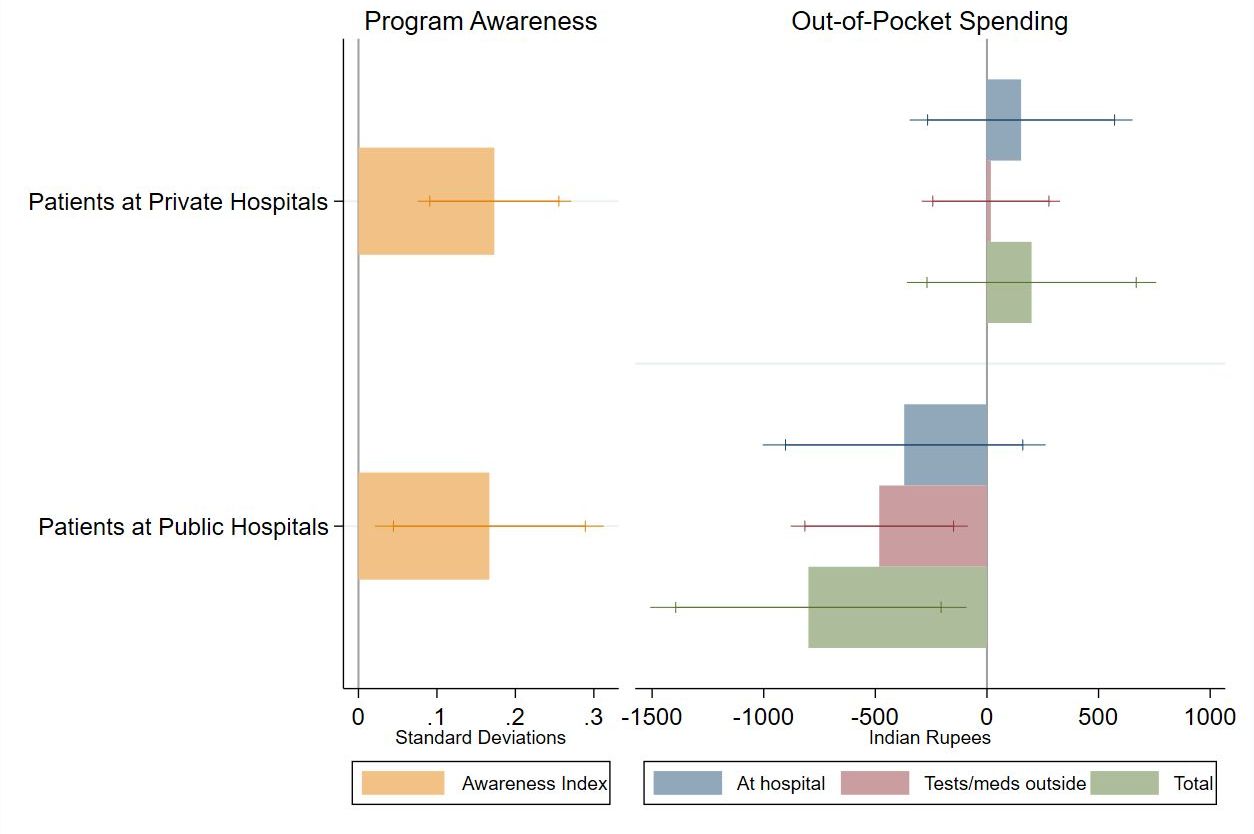

However, we found that providing patients with phone-based information led to large and significant increases in their awareness of their BSBY entitlements (see Figure 2). We find a 0.17 standard deviation2 gain on an awareness index which comprised of six questions, and these effects are as big (or bigger, in some cases) among poorer, less educated, and female patients. With the information in hand, patients exercised both ‘voice’ and ‘exit’ – they increased the amount they negotiated and were also more likely to switch to other hospitals relative to those in the control group.

Figure 2. Impact of phone-based information on awareness and spending

Notes: i) The figure presents the impact of the phone-based information intervention on patient awareness of their benefits under the BSBY insurance programme, and on their out-of-pocket expenditure for their care in the last month. ii) Patients are split by whether they were visiting a public or private hospital at baseline.

While these actions did not decrease out-of-pocket payments on average, there was substantial heterogeneity by hospital sector. At private hospitals, the information did not lead to a change in what patients paid out-of-pocket. Even though patients were more likely to bargain and some (though not by a huge number – we noted a 5.4 percentage point change) switched to other hospitals, the hospitals were relatively unreceptive to bargaining, and those who switched were more likely to go to a hospital that didn’t accept public insurance.

At public hospitals, however, the information led to a 35% (approximately Rs. 800) decrease in out-of-pocket payments. This impact was driven by an increase in patients requesting free medications and tests from the hospital (using ‘voice’ as opposed to ‘exit’). Indeed, the reduction in payments incurred by public hospital patients came from a decrease in the likelihood and amount of payment for tests and medicines purchased outside the hospital rather than a reduction in expenses incurred at the hospital. In the control group, 53% of public hospital patients reported having to get and pay for these items outside the hospital (largely because hospital staff say they are out of stock or unavailable on the premises); this decreased by 13.2 percentage points in the treatment group.

Our findings demonstrate that simple phone-based information provision can be an effective method for strengthening awareness of public benefits, including complex health insurance programmes.

Conclusion

Expanding healthcare access and protection from health-related financial risks are global priorities, and government health insurance programmes are being rapidly scaled up around the world as a means of achieving these goals. Our research adds to the body of evidence on the need to increase accountability in these systems, and shows that information interventions are one tool to help reach that goal.

In India, the information intervention helped beneficiaries of public health insurance advocate for themselves at public hospitals and get their due benefits. The intervention didn’t have the same impact at private hospitals, however, indicating that changing the pricing behaviour of profit-maximising private companies may require top-down monitoring or changes to hospital financial incentives.

This research suggests that bottom-up programmes can help hold public hospitals accountable and reduce healthcare costs for low-income families. Since public hospitals serve poorer and more socially disadvantaged individuals than private hospitals, the information intervention is likely to greatly benefit poor households who would otherwise be paying out-of-pocket.

However, national health insurance programmes will likely continue to need appropriately designed incentives, including adequate monitoring and accountability systems, to achieve their goals and benefit the target population.

Notes:

- These patients were selected because i) dialysis is a high frequency, long term, and expensive service, so the potential gains from information are substantial, and ii) it is a standardised service, with relatively little variation in treatment procedure across patients and hospitals, and iii) unlike much of the research, which focuses on primary care, it allows us to study the effects of patient-driven accountability in the context of specialized, life-saving hospital care.

- Standard deviation is a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values from the mean value of that set.

Further Reading

- Barik, D, S Pramanik and S Desai (2020), ‘Insured but Not Covered: Rising Insurance Coverage Should be Accompanied by Awareness of Entitlements’, NCAER National Data Innovation Centre Measurement Brief 2020-02.

- Bukhman, Gene, et al. (2020), “The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion”, The Lancet, 396(10256): 991-1044.

- Devarajan, Shantayanan and Ritva Reinikka (2004), “Making Services Work for Poor People”, Journal of African Economies, 13: i142-i166.

- Dupas, Pascaline and Radhika Jain (2023), “Can beneficiary information improve hospital accountability? Experimental evidence from a public health insurance scheme in India”, Journal of Public Economics, 220. A version of this paper is available here.

- Giedion, U, E Andrés Alfonso and Y Díaz (2013), “The Impact of Universal Coverage Schemes in the Developing World: A Review of the Existing Evidence”, UNICO Studies Series No. 25, World Bank.

- Hirschman, AO (1972), Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, Harvard University Press.

- Karan, Anup, Winni Yip and Ajay Mahal (2017), “Extending health insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare”, Social Science & Medicine, 181: 83-92.

- Malani, A, et al. (2021), ‘Effect of Health Insurance in India: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, NBER Working Paper 29576.

- Nandi, Sulakshana, Helen Schneider and Priyanka Dixit (2017), “Hospital utilization and out of pocket expenditure in public and private sectors under the universal government health insurance scheme in Chhattisgarh State, India: Lessons for universal health coverage”, PLoS ONE, 12(11):

- Rao, Mala, et al. (2012), “A rapid evaluation of the Rajiv Aarogyasricommunity health insurance scheme in Andhra Pradesh, India”, BMC Proceedings, 6(O4).

- Shukla, R and A Kapur (2022), ‘Budget Briefs: Ayushman Bharat - GoI, 2021-22’, 13(2), Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research.

- Sriram, Shyamkumar and M Mahmud Khan (2020), “Effect of health insurance program for the poor on out-of-pocket inpatient care cost in India: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey”, BMC Health Services Research, 20(839).

- WHO (2022), ‘Monitoring progress on universal health coverage and the health-related Sustainable Development Goals in the South-East Asia Region - 2022 update’, World Health Organization.

- World Bank (2003), ‘World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People’.

24 April, 2023

24 April, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.