India’s largest health insurance programme is targetted at poor and vulnerable populations who would be least able to afford medical care. However, this article by Chhabra and Smith shows that a large proportion of beneficiaries of both national and state health insurance schemes belong to the top half of the welfare distribution. They suggest using alternative eligibility criteria to increase awareness and uptake of schemes, as a path towards universal health coverage.

The economic and health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has hit households hard all around the world. This is true not only for the poor, but also for the near-poor and vulnerable, including those in the informal sector who are often not covered by social insurance programmes. The convergence of economic and health shocks during the pandemic has brought renewed focus to the objective of universal health coverage (UHC). Ensuring protection against the financial consequences of ill health – due to COVID or any other cause – is an unfinished agenda in many countries.

In India, the largest health insurance programme is the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), a fully government-funded scheme launched in 2018 providing coverage for hospitalisation costs up to Rs. 500,000 per household annually. It is targetted to the bottom 40% of the population (or 500 million people) based on the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011. This group is the least able to afford a potentially catastrophic, high-cost hospitalisation, and the most likely to be (further) impoverished by medical bills. In over 15 states, PM-JAY is co-branded with state insurance schemes that carry their own names; while some details may differ, PM-JAY and state schemes are broadly the same programme. However, some states such as Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, and Uttarakhand have significantly expanded eligibility.1

Does targetted health insurance reach its intended beneficiaries?

Targeting specific population groups in health insurance programmes is consistent with reforms undertaken in many other middle-income countries over the past 20 years, whereby tax-funded health financing programmes have aimed to prioritise beneficiaries in lower socioeconomic strata while also serving as a vehicle for broader institutional reforms. Targetted programmes can be a useful stepping-stone on the journey towards UHC.2

Whatever the merits of a targetted approach on paper, it is important to monitor implementation on the ground. Between policy intent and reality, operationalising a targetted approach may encounter many potential pitfalls, including errors of exclusion (that is, households in the bottom 40% being deemed ineligible), errors of inclusion (those not in the bottom 40% gaining access to the programme), shortcomings in outreach and communications (such as eligible households not being aware of the programme or their eligibility), and barriers to registration (for example, inaccessible points of service, onerous requirements with respect to proof of identity or mobile access, or informal payments to scheme gate-keepers).

With these challenges in mind, robust monitoring of beneficiary targeting can generate useful evidence about whether PM-JAY is successfully reaching its intended population. To inform this issue, new questions were added to a survey instrument administered to 129,036 households across 28 states and Union Territories (UTs)3 between January and April 2021. The survey was implemented by the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE) as part of its regular panel. In contrast to other health-related surveys (such as the National Family Health Survey or National Sample Survey (NSS) health round), the questionnaire explicitly asked about both PM-JAY and the appropriate state-specific insurance scheme, by name.

Who is utilising PM-JAY benefits?

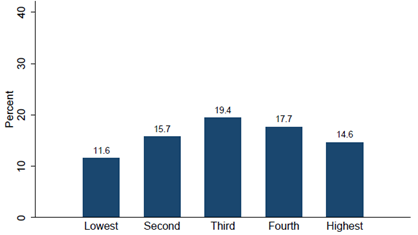

The question remains: is PM-JAY reaching the bottom 40% of the population? Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents who are enrolled in PM-JAY by socioeconomic quintile (as derived from a large number of questions about household consumption). Enrolment is highest in the middle quintile, at almost 20%, and lowest in the poorest quintile at 11.6%. There are also significant numbers of enrollees in the top two quintiles. In fact, the findings suggest there are more PM-JAY beneficiaries in the top half of the overall population in terms of welfare distribution than in the bottom half. Targeting performance therefore falls significantly short of fulfilling the objective to cover the bottom 40%.4

Figure 1. Proportion of households enrolled in PM-JAY, by quintile

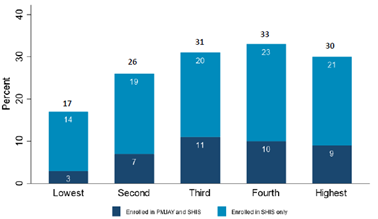

Figure 2 shows the distribution of state insurance scheme enrollees by socioeconomic quintile. It distinguishes between those reporting only state scheme enrolment and those who also said they were PM-JAY beneficiaries.5 Similar to the PM-JAY picture, Figure 2 reveals that a large share of enrolled households are in the richer quintiles – in fact, even more so. However, it is also true that many states have expanded eligibility to include significantly more than the poorest 40% of the state population, and in some cases are aiming for universal coverage. In these states, higher coverage among upper quintiles may be consistent with policy choices.

Figure 2. Proportion of households enrolled in state health insurance schemes, by quintiles

It is especially notable that Figure 1 reveals that PM-JAY enrolment is highest in the third quintile, quite the opposite of the conventional narrative of the ‘missing middle’. According to this theory, a country may neglect middle-income groups if a health financing system is built around the twin pillars of subsidised insurance for the poor and contributory, formal sector coverage for the richest. The enrolment pattern shown here reinforces the message that the policy priority should remain squarely on the poorest segment of the population, among whom PM-JAY coverage is still the lowest.

In brief, the shortcomings of the current targeting approach are apparent. SECC is now over 10 years old and has not been updated, while inevitably there would have been significant household changes since then. SECC-based targeting is especially difficult to apply in dynamic urban environments. There is no obvious familiarity with SECC among households since it is not commonly used in other large programmes, creating uncertainty about their eligibility status, which serves as a barrier to access.

Alternative approaches to targeting

What can be done? A potential alternative to SECC would be to apply the National Food Security Act (NFSA) eligibility criteria which is used for subsidised food grains under the Public Distribution System (PDS). NFSA offers important advantages over SECC, since it is dynamic (regularly updated), managed directly by states, and is well understood by the population. Fair price shops are among the most common points of interface between India’s governments and citizens. They would offer a natural platform for PM-JAY communication efforts, and accordingly could improve awareness levels among the lower quintiles. However, a potential disadvantage is that NFSA ration cards might be too easily obtained by ineligible households through informal payments, and this problem could spill over to PM-JAY.

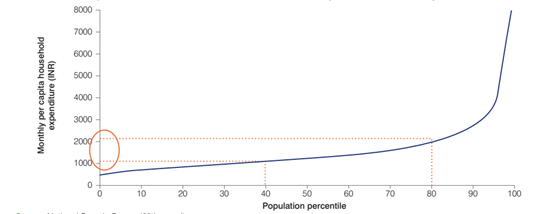

Although a transition to NFSA eligibility criteria would imply an increase in PM-JAY coverage to about 65% of the population, there is no long-term rationale for keeping eligibility at the current 40%. A far larger share of India’s population needs health insurance coverage. Figure 3 shows that the difference in monthly mean per capita household consumption between the 40th and 80th percentiles of the welfare distribution is only about Rs. 1,000, far less than a typical hospital bill. Indeed, this is why the goal is universal coverage: because the majority of India’s population is vulnerable to a catastrophic or impoverishing health shock, not just the lower quintiles. There is also abundant evidence from other countries that eliciting health insurance contributions (mandatory or voluntary) from the informal sector is very difficult and not a realistic pathway to UHC.

Figure 3. Distribution of consumption expenditure across quintiles

The main short-term obstacle to universal health coverage is the additional fiscal burden that a coverage expansion would entail, especially in states where the NFSA eligible population share is very high. But this fiscal constraint should be seen in perspective. It is also true that India’s prioritisation of health spending – as measured by the share of total government expenditures allocated to health (by the Government of India and states combined) – is among the lowest in the world. At less than 4%, India ranks 181 out of 187 countries worldwide according to the World Development Indicator database. Thus, the public purse remains a relatively untapped source for health financing in India.

In brief, a strong case can be made that significantly increasing the target population – potentially by applying NFSA criteria – is the next logical step on PM-JAY’s expansion path. A future in which no population segment is missing from India’s health coverage landscape will hopefully soon become reality.

Notes:

- In some states, only those households that are eligible under PM-JAY are covered under the co-branded banner, while other states have opted to expand coverage to ’extension populations’ beyond the PM-JAY list using their own eligibility criteria and fully funded by state resources (that is, without Union Government co-financing, as is the case for core PM-JAY beneficiaries). Delhi, Odisha and West Bengal do not participate in PM-JAY.

- It should be noted that some countries have also successfully pursued a consistently universalist approach, without targeting.

- A few UTs and northeastern states were not covered.

- For additional findings, see Bhatnagar et al. 2022.

- Since PM-JAY and state schemes are co-branded and name recognition can vary, overall coverage is measured by the share of households reporting enrolment in either one or both schemes.

- See, for example, evidence from Indonesia (Banerjee et al. 2021), Philippines (Capuno et al. 2016) and Vietnam (Wagstaff et al. 2016).

Further Reading

- Banerjee, Abhijit, et al. (2021),"The Challenges of Universal Health Insurance in Developing Countries: Experimental Evidence from Indonesia's National Health Insurance", American Economic Review, 111(9): 3035-63.

- Bhatnagar, A, S Chhabra, N Manchanda and O Smith (2022), ‘PM-JAY Awareness, Enrolment and Targeting: Evidence from a National Household Survey’, Policy Brief No. 11.

- Capuno, Joseph J, Aleli D Kraft, Stella Quimbo, Carlos R Tan Jr and Adam Wagstaff (2016), “Effects of Price, Information, and Transactions Cost Interventions to Raise Voluntary Enrollment in a Social Health Insurance Scheme: A Randomized Experiment in the Philippines”, Health Econ, 25(6): 650-62.

- Wagstaff, Adam, Ha Thi Hong Nguyen, Huyen Dao and Sarah Bales (2016), “Encouraging Health Insurance for the Informal Sector: A Cluster Randomized Experiment in Vietnam”, Health Econ, 25(6): 663-74.

19 October, 2022

19 October, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.