Lifetime risk of maternal death in developing countries is 33 times higher as compared to the developed world. This article examines the role of cultural norms in influencing maternal morbidity and mortality. It finds that, in societies with a strong cultural preference for sons and generally poor reproductive health conditions, women with a first-born girl are more likely to suffer from anaemia, and less likely to survive to older ages, relative to those with a first-born boy.

An estimated global total of 10.7 million women died from maternal causes in the 25 years between 1990 and 2015. Nearly all of these deaths were concentrated in developing countries (mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia), where the lifetime risk of maternal death is, on average, about 33 times higher than in the developed region (World Health Organization (WHO), 2015).1

In recent research (Agarwal and Milazzo 2019), we study the role of cultural factors in influencing maternal morbidity and mortality in the developing world. Our main focus is on son preference. Previous work for India suggests that, compared to women with first-born sons, women with first-born daughters are more likely to be anaemic and appear to have lower likelihood of survival. This is, at least partially, because son preference induces these women into fertility behaviours that are medically known to be associated with a higher risk of maternal morbidity and mortality (Milazzo 2018). We then ask a cross-cultural question: if son preference and the harmful fertility behaviours that follow the birth of a daughter are indeed partly responsible for the high mortality of Indian women, then, is the higher morbidity and the decline in survival into older ages especially pronounced in countries with high son preference and poorer overall maternal health conditions? And what are other socioeconomic and cultural determinants of such a decline in the survival of women with first-born girls across countries?

In an attempt to answer these questions, we use data from 218 demographic and health surveys covering 74 countries – facing different intensities of son preference and maternal health conditions – between 1990 and 2015.

Measuring son preference and maternal health conditions

In their quest for a son, women with a first-born girl may behave differently as compared to those with a first-born boy, say by increasing their fertility, reducing the use of contraceptives, and/or reducing birth spacing until their need for a son is met. To measure son preference, we study such differential fertility behaviour by asking five questions for every country-year: compared to women with a first-born boy, are women with a first-born girl significantly more likely to (1) have a greater number of children; (2) desire more children; (3) reduce spacing between the first and the second birth; (4) have ever terminated a pregnancy; and less likely to (5) use contraception?2. We believe that considering these various behavioural responses to having a first-born girl captures multiple possible manifestations of son preference, which is appropriate given the diverse cultural and reproductive norms in our multi-country study. We categorise a country-year as having high son preference if it shows son preference in at least three of the above five dimensions.3

To capture health conditions, we define a high maternal mortality risk indicator at the country-year level, if the lifetime risk of maternal death is greater than or equal to the year-specific median lifetime risk of maternal death, for all developing countries covered in the World Development Indicator database.

Joint role of son preference and health conditions in women's mortality: Suggestive evidence

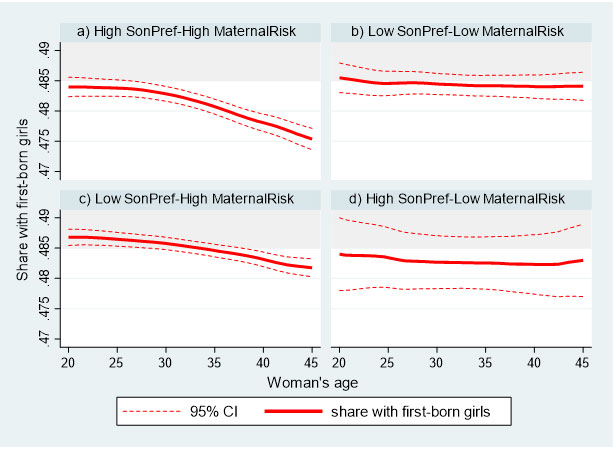

Figure 1 demonstrates our first finding. It shows suggestive evidence that the share of women with a first-born girl who survive to older ages is the lowest (and well below the biological range, represented by the shaded area) in places with both high son preference and high maternal mortality risk (Panel a). This survival disadvantage in the reproductive ages appears to be reduced in country-years that are characterised by either lower son preference or lower maternal mortality risk (Panels c and d). On the other extreme, in countries with low son preference and low maternal mortality risk, we find that there is no survival disadvantage for women with a first-born girl (Panel b).

Figure 1. Share of women with first-born girl declines the most with women’s age in areas with both high son preference and high maternal mortality risk

We also find that the declining trend in the share of women with a first-born girl who survive to older ages, is concentrated among those of lower socioeconomic status who likely have limited access to healthcare, and are thus more vulnerable to experience harmful health consequences.

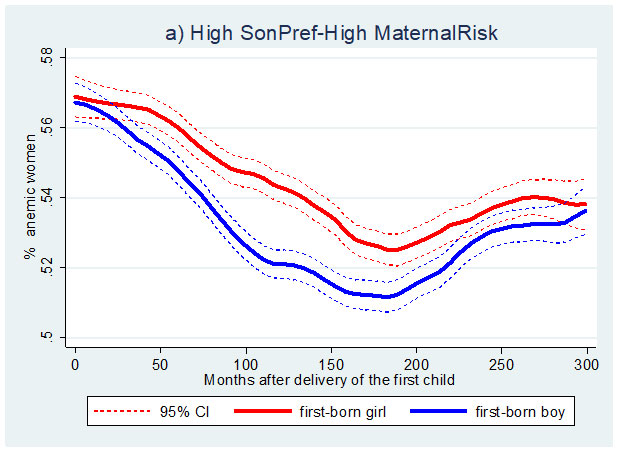

Next, we turn our attention to women’s morbidity, specifically anaemia – an indirect cause of maternal mortality.4 Figure 2 shows that in places with high son preference and high maternal mortality risk, women with a first-born girl are more likely to be anaemic compared to women with a first-born boy, after their first child’s birth. Importantly, there is no differential incidence of anaemia immediately after birth. This is consistent with the idea that women with a first-born girl engage in fertility behaviours that are medically known to increase the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality after the birth of their first child. Moreover, the anaemia patterns for the remaining three country-year groups do not reveal any significant differences by the first child’s sex.

Figure 2. Women with first-born girl experience higher likelihood of anaemia in high son preference and high maternal mortality risk areas

Summarising the decline in the share of women, by their first child’s sex

As seen in Figure 1, we are inferring the higher mortality of women with a first-born girl by examining the share of women with first-born girls by their age (that is, the declining share below the biological range, especially pronounced in Panel a). To quantify such a decline concisely (which we call ‘imbalance’), we estimate the 'slope' for every country-year.5 Therefore, imbalance provides a single summary measure, conveying whether, for each country-year, women with a first-born girl may be less likely to survive to older ages.

Socioeconomic and cultural correlates of imbalance

Having a single summary indicator of imbalance allows us to study its association with multiple factors across countries. We find several significant correlations. Economic factors, such as greater urbanisation and a lower gender gap in school enrolment, are both associated with a lower probability of imbalance. On the health front, as expected, a higher proportion of skilled birth attendance(indicating better provision of reproductive healthcare services) is negatively associated with imbalance. A higher prevalence of anaemia has a strong positive correlation with the likelihood of imbalance in a country-year, reinforcing our earlier findings on anaemia.

We also find some compelling correlations with cultural and historical variables. For instance, a higher share of women who believe that wife-beating is justified is positively associated with imbalance. Moreover, a lower average age at first marriage, which captures norms around marriage and reproduction, is positively correlated with imbalance. This is in line with previous literature finding that early marriage is generally associated with lower female education and autonomy, and a higher risk of maternal-health problems (Jensen and Thornton 2003). Interestingly, we find that a higher intensity of traditional plough use in agriculture – as a measure of the historical division of gender roles – is positively associated with our contemporaneous measure of imbalance. This finding is consistent with previous research documenting the persistence of cultural norms associated with historical agricultural practices in affecting women’s labour force participation and status in contemporary times (Alesina et al. 2013).6 Additionally, matrilocal post-marital residence is negatively associated with imbalance (while patrilocality shows a positive correlation).

Finally, as expected, we find strong evidence of the joint positive effect of son preference and maternal mortality risk on the likelihood of imbalance, which persists even after we control for a host of economic, health, cultural, and historical correlates of imbalance. In terms of changes over time, our first investigation does not reveal any evidence that the outcomes examined are worsening, but also not improving, for women with first-born girls.

Conclusion and policy relevance

The findings of this multi-country research emphasise the interactive role of economic and cultural factors in influencing maternal morbidity and mortality, and show the far-reaching negative health consequences of son preference. Ideally, mitigating the negative effects of son-preferring fertility behaviour on maternal health requires policies on at least two fronts: First, interventions to change deep-rooted discriminatory cultural norms and attitudes towards women (Beaman et al. 2009, La Ferrara 2016, Dhar et al. 2018, Banerjee et al. 2019). Second, public health interventions targeted to treat maternal anaemia and improve women’s access to reproductive health services should be implemented (as also emphasised in two of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals).7

Notes:

- Lifetime risk of maternal death is the probability that a 15-year-old female will die eventually from a maternal cause – assuming that current levels of fertility and mortality (including maternal mortality) do not change in the future – taking into account competing causes of death (WHO, 2015).

- The assumption that the sex of the first-born child is random is widely supported in the literature (for instance, Dahl and Moretti 2008, Heath and Tan 2018).

- Our findings are largely unchanged by choosing different cut-offs to define high son preference, and to excluding India from the analysis.

- Most maternal deaths are due to direct causes including severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure, complications from delivery, and unsafe abortions. Anaemia, malnutrition, and pre-existing conditions such as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), diabetes and cancer, are some of the indirect causes (Say et al. 2014, Ronsmans and Graham 2006). Some studies attribute as much as one quarter to 40% of maternal deaths to anaemia (Gragnolati et al. 2005, Kalaivani 2009).

- Specifically, the indicator of imbalance equals 1 if the slope is significantly negative for any of the age groups, and if the average share of women with first-born girls in the age group 30-49 is less than the minimum biological sex ratio.

- As argued in Boserup (1970), and later shown by Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn (2013), societies with historical plough usage tended to have lower historical female labour force participation (as men have comparative advantage in agriculture that relies on plough use), and show lower female labour force participation and less equal gender norms persisting into modern times.

- Goal 3 is to ‘Attain healthy life for all at all ages’, and Goal 5 is to 'attain gender equality, empower women and girls everywhere’. The specific target under these two goals is to ‘Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights’.

Further Reading

- Agarwal, N and A Milazzo (2019), ‘Son Preference, Maternal Health and Women’s Survival: A Cross-Cultural Analysis’, Working Paper.

- Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano, Nathan Nunn (20130, “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2):469-530.

- Banerjee, A, E L Ferrara, and V H Orozco-Olvera (2019), ‘The entertaining way to behavioral change: Fighting HIV with MTV’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 26096.

- Beaman, Lori, Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, Rohini Pande and Petia Topalova (2009), “Powerful women: does exposure reduce bias?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4):1497-1540.

- Boserup, E (1970), Woman’s Role in Economic Development, George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London.

- Dahl, Gordon B and Enrico Moretti (2008), “The Demand for Sons”, Review of Economic Studies, 75(4):1085-1120.

- Dhar, D, T Jain and S Jayachandran (2018), ‘ Reshaping Adolescents’ Gender Attitudes: Evidence from a School-Based Experiment in India', NBER Working Paper No. 25331.

- Gragnolati, M, M Shekar, M Dasgupta, C Bredenkamp and Y-K Lee (2005), ‘India's Undernourished Children: A Call for Reform and Action’, Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper, World Bank.

- Heath, Rachel and Xu Tan (2018), “Worth fighting for: Daughters improve their mothers' autonomy in South Asia”, Journal of Development Economics, 135(C):255-271.

- Jensen, Robert and Rebecca Thornton (2003), “Early female marriage in the developing world”, Gender and Development, 11(2):9-19.

- Kalaivani, K (2009), “Prevalence & Consequences of Anaemia in Pregnancy’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, 130(5):627-633.

- La Ferrara, Eliana (2016), “Mass media and social change: can we use television to fight poverty?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 14(4):791-827.

- Milazzo, Annamaria (2018), “Why are adult women missing? Son preference and maternal survival in India”, Journal of Development Economics, 134:467-484.

- Ronsmans, Carine and Wendy J Graham (2006), “Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why”, Lancet, 368:1189-1200.

- Say, Lale, Doris Chou, Alison Gemmill, Özge Tunçalp, Ann-Beth Moller, Jane Daniels, A Metin Gülmezoglu, Marleen Temmerman and Leontine Alkema (2014), “Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis”, The Lancet Global Health, 2(6):e323-e333.

- World Health Organization (2015), ‘Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division’, November 2015.

16 July, 2020

16 July, 2020

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.