The recent imposition of a ban on wheat exports, in a bid to ensure food security, has meant that farmers will not realise the benefits from the recent increase in global wheat prices. In this post, Kumar and Mandal discuss the trade-off between food security and farmers’ income and the strategies and policy options that can be employed to balance these priorities, amidst international conflict and climate change.

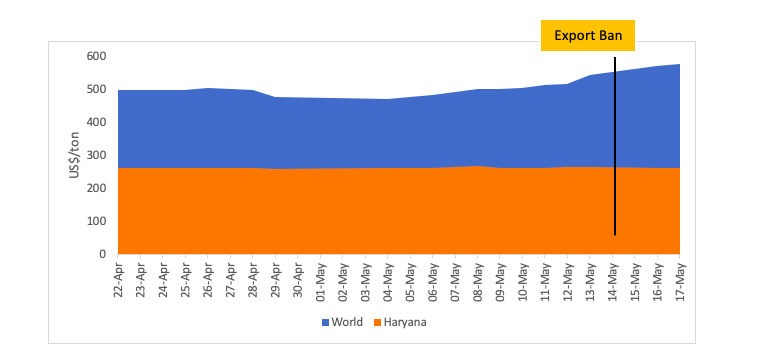

India is the second largest producer of wheat in the world and accounts for around 14.1% of global wheat production1. The country is gradually emerging as a global supplier of wheat, which is evident from recent exports of wheat to the tune of 7.85 million tonnes up to March in Financial Year (FY) 2021-22, an all-time high and a sharp increase from 2.1 million tonnes in the previous year (FY2020-21). In February 2022, as per Second Advance Estimates of the Government of India, it was expected that India would set a new record of producing 111.32 million tonnes of wheat. However, this was subsequently revised downwards to the extent of 105 million tonnes for the 2021-22 crop year (see Figure 1).

A key factor that led to the decline in wheat production was the negative effect of heat stress at the dough stage2 that affected the grain filling. As per the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the north-west and central parts of India experienced two early spells of heatwaves during the middle and end of March 2022 – this sudden rise in temperature resulted in a decline of wheat productivity by 10-15%. Turmoil in the international wheat market due to the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has disrupted the global supply chain of wheat, increasing the opportunities of wheat exports from India.

Figure 1. Wheat production trends in India

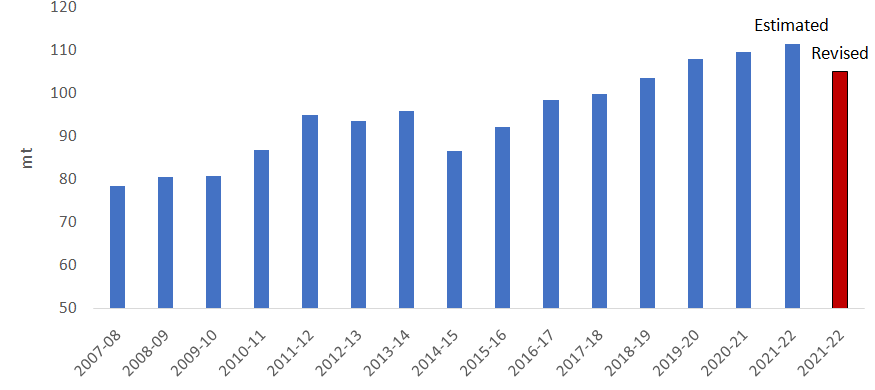

However, declining wheat yield due to the sudden rise in temperature has affected government procurement, as well as India’s ambitious export plan, in favour of ensuring food security within the country. Until 10 May 2022, the government had procured 17.8 million tonnes of wheat, which was around 59% less than the previous year’s purchase (43.34 million tonnes) and roughly 60% less than the expected purchase target for FY2022-23 (see Figure 2).

Based on our observations in the field and discussions with farmers and other key stakeholders, we find that shortfall in wheat procurement can be attributed to a number of factors: first, farmers preferred to sell their wheat produce to private traders, as the price offered by them was higher to the tune of Rs. 150-200 per quintal above the minimum support price (MSP) of Rs. 2,015 per quintal offered by government agencies. Additionally, private players purchased directly from the farmers’ fields – this was another incentive for farmers in terms of saving on transportation, loading and unloading charges, market fee etc. Therefore, private traders become the obvious choice for farmers to sell their produce. Second, many farmers, mostly large and medium farmers, also chose to hold on to their wheat produce in anticipation of a further hike in wheat prices in the international market due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The higher prices, brought about by strong export demand, were expected to compensate part of their losses of income due to the reduced production caused by heat stress. However, their expectation has not been realised, as on 13 May 2022, the government chose to ban wheat export with the view to ensure food security in the country. Third, the shrinking of grains due to heatwaves in wheat-growing areas led to grain stock not meeting Fair and Average Quality (FAQ) norms, which in turn became a technical hurdle in wheat procurement by government agencies. On 15 May, the FAQ norms were revised downwards and smaller grains were accommodated through Under Relaxed Specifications (URS) category, but this undue delay had a negative impact on the procurement process.

Figure 2. Wheat procurement for central pool

The trade-offs between food security and farmers’ income

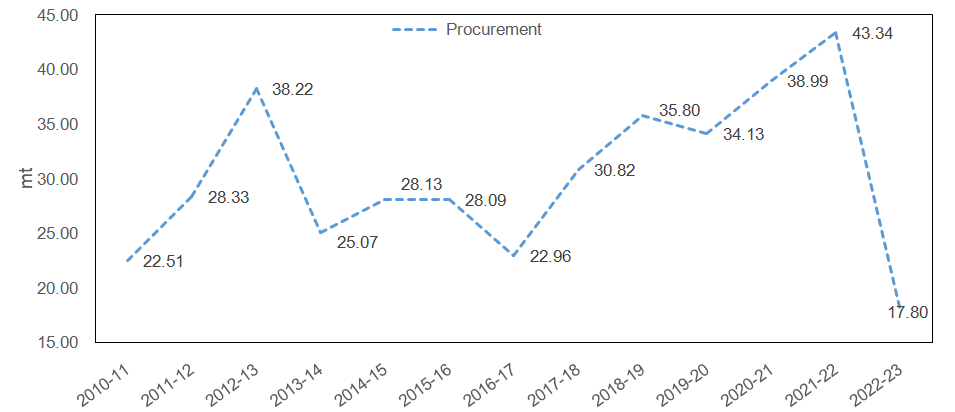

The ban on wheat exports led to depressed domestic wheat prices. For instance, Figure 3 shows that from 22 April to 12 May, that is, before the ban, prices in the international market were, on average, US$ 498 per tonne, as compared to domestic market price (for instance, in the state of Haryana) averaging US$ 263 per tonne. After the imposition of the ban on exports from India, international prices began rising significantly, to US$ 545, US$ 570, and US$ 576 per tonne, well over the pre-export ban price of US$ 518 per tonne on 12 May, and are continuing to rise.

On the other hand, prices in the domestic markets have either been the same or have fallen (as seen in Figure 3), as domestic prices of agricultural commodities are highly integrated with international prices. However, if government interventions or restrictions are enforced, it results in market distortions which do not favour domestic producers, and affect price integration. Strategically, the government sought to protect consumers, ensuring that food was available to the masses at affordable prices rather than allowing the export of wheat in the global market – thereby foregoing the higher returns expected by producers.

Figure 3. Wheat prices in Haryana and the world, in US$ per tonne

Source: International Grain Council and Directorate of Marketing & Inspection, Government of India (2022

Impact on wheat-growing farmers

The three-fold impacts of heat-stress, rising fuel prices and export ban, on wheat growers were evident as: (i) The unprecedented rise in temperature in the month of March has been viewed as a clear manifestation of climate change, the effects of which are likely to increase in the coming years. In Punjab and Haryana, as per our calculations, this resulted in a loss of Rs. 10,609 to 15,913 per hectare3; (ii) The ban on wheat exports, after which prices started to fall in some areas (for instance, in Haryana and Punjab), was another setback for farmers. However, given the dynamic situation of the international market, it is difficult to assess the likely impact on the domestic market prices if there had been no ban on wheat export. In an integrated global market, if there was no market distortion and the export ban had not been imposed, the domestic price of wheat would have likely been positively correlated with global prices and farmers would have possibly received an additional Rs. 100-200 per quintal; (iii) farmers have also been under stress on account of surging fuel prices. Higher fuel prices would also directly affect the cost of cultivation, since wheat is one of the most mechanised crops in India. Whether the farmers’ losses are going to be compensated by the government through the announcement of an additional bonus to wheat this year is yet to be seen.

Strategies and policy options

The export ban, combined with rising fuel prices and heat-stress, has led to policy debates on several related issues, particularly – what could be the best possible solution for the government to safeguard farmers’ interest, while also ensuring food security in the country?

The ban on wheat exports, apart from being a blow to India’s image of being a credible supplier of wheat in the international market, also led to farmers losing the opportunity to realise better prices this year. The now repealed 2020 farm laws, particularly the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, could have provided farmers an opportunity to realise better prices by giving them some leeway for maintaining stock limit.4

Once again, such a move has also reinforced the allegation of the government being biased toward consumers at the expense of farmers. As per the buffer stock norms, the total stock required as of April was 21.04 million tonnes (13.58 and 7.46 million tonnes of rice and wheat, respectively). However, the actual stock was much higher than these norms – with 32.2 and 24.7 million tonnes of rice and wheat, respectively, being available (FCI, 2022). In such a case, open market distribution in domestic and international markets would have been a suitable option, as this would have benefitted farmers without affecting the interests of domestic consumers.

The potential aggressive buying behaviour of private players, on account of market expectations of a surge in international wheat prices, could have also been factored into the procurement plan of the government. In order to be competitive with private players, an additional bonus of Rs. 200-300 per quintal over the MSP could be offered during procurement. Such an offer can be made as a short-term policy measure to ensure procurement, while also protecting farmers’ income.

As the more acute impact of climate change seems inevitable, heat tolerant varieties of wheat (such as DBW 107 and DBW 1735) should be promoted, and agronomic strategies such as advancing sowing dates, applying additional doses of nitrogen fertilisers, and irrigation at the grain filling stage can be undertaken, to moderate the effect of heat stresses. Heat stress and its consequences (shrinkage grains) can also be taken into consideration while revising the FAQ norms to avoid undue delays in wheat procurement by government agencies.

Although the situation this year is unprecedented, incidents of heat stress are likely to increase in the future. A ‘quick response strategy’ needs to be devised, in consultation with all the stakeholders involved, in order to maintain both food security and a secure income for farmers.

Views expressed in this article are personal and do not reflect the opinions of any organisations.

I4I is on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Global wheat production was 761 million tonnes in the year 2020 (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2022).

- The dough stage is a critical stage of grain formation in which kernels rapidly accumulate starch and most of their dry weight. Kernels attain a doughy consistency at this stage.

- In Punjab and Haryana, due to heat-stress the decline in production is around 10-15% of the average wheat productivity (around 4.9 tonnes per hectare) with the average prevailing price of Rs. 21,650 per tonne

- The Act stipulated that a stock limit may be imposed only if there is: (i) 100% increase in retail price of horticultural produce; and (ii) 50% increase in the retail price of non-perishable agricultural food items. The increase will be calculated over the price prevailing immediately preceding 12 months, or the average retail price of the last five years, whichever is lower.

- DBW is the prefix name referred to wheat varieties released from ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research)-Indian Institute of Wheat and Barley Research, Karnal, Haryana.

Further Reading

- Directorate of Economics and Statistics (2020), ‘Agricultural Statistics at a Glance’, Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Farmers Welfare, Directorate of Economics and Statistics.

08 June, 2022

08 June, 2022

By: Danish 09 June, 2022

How "Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, could have provided farmers an opportunity to realise better prices by giving them some leeway for maintaining stock limit" This would have rather benefited to the private players who had the wherewithal to create large warehouses & cold storage who would have taken the 50% gap to hoard/stockpile using extensive forecasting & speculation instruments . I never saw farmer (even a big one) stockpiling hundreds of tons for reasons abound. Now the ECA, if I can recall, does not impose the stock limit on the processors or value chain participants or exporters. Any private player will not invest in warehouses & cold storage without using the leverage of full supply chain including but not limited to being processors, value chain participator and to whatever possible extent being a exporter. Why would private players would pay the farmers anything from a margin of 50%. On the contrary they would obliterate the small traders who provide multitude of supports other than outright purchasing from the farmer from the inception till delivery. This systemic strangulation of small traders will put the farmers at the mercy of private players either directly or for a better word " a death by thousand cuts" I am hopeful that you would have some solid reasoning of ECA stock limit waiver benefit accruing to the farmers rather than private business or at least a major chunk. How 50% would be shared in the best case scenario. Regards