The ongoing wave of technological revolution across the globe is set to fundamentally change the way goods are produced and services are delivered. Using a task-based framework, this article seeks to examine the impact of technology on the nature of jobs in India. It finds that in keeping with global trends, non-routine cognitive task intensities of jobs have increased, and manual task contents – both routine and non-routine – have declined.

Technological progress has been the single most important driver of economic growth in the modern history of mankind. Over the period, technological innovations have increased labour productivity and made life much easier. However, despite these gains technological innovations have always created a panic of technological unemployment and the current wave of information and communication based technological progress is no exception. The recent spurt in digital innovations and consequent increase in automation has once again instilled the fear of mass technological unemployment. It has been argued that if digital innovations continue at the current pace, machines, in the near future, will be able to substitute labour in most of the economic activities, leading to a workless world (Rifkin 1995). However, these predictions have come from public activists and not from accredited researchers. Instead, citing the historical experience, mainstream economists have tried to dispel these concerns. They have argued that there exist many compensation mechanisms which, in the long run, can counterbalance the initial negative impact of labour-saving technological change (Vivarelli 2012). Although technology-induced end of work hypothesis may be far-fetched, there is a consensus that the ongoing digital revolution is set to fundamentally change the way goods are produced and services are delivered. Since computers are very good at performing routine and repetitive tasks, it is anticipated that computer-controlled machines will replace humans in these tasks. In fact, various studies have already shown that the routine task content of jobs has indeed been declining worldwide (Autor et al. 2003, Michaels et al. 2014).

Evolution of task content of jobs in India

The Indian economy is not isolated from the ongoing wave of the technological revolution as the use of digital technology has become quite visible in many sectors. However, little is known about its impact on jobs. We examined this issue in a task-based framework. Data needed for the estimation of task content of jobs has been drawn from two different sources. Following the standard literature, we have used the Occupational Information Network (O-Net1) database as a source of information on task intensities of different occupations. Detailed information on employment in the Indian economy has been taken from several rounds of the Employment and Unemployment Survey (EUS2). Combining the O-Net and Employment Unemployment Surveys data, we calculated the five main task content measures – non-routine cognitive analytical (NRCA), non-routine cognitive interactive (NCRI), routine cognitive (RC), routine manual (RM), and non-routine manual (NRM) – by adding up the appropriate task items, as depicted in Figure 1 (Vashisht and Dubey 2018).

Figure 1. Task content measures

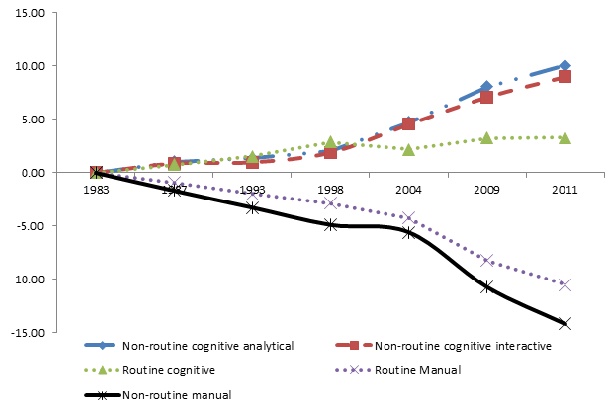

Our results suggest that India, by and large, is following the global trend as non-routine cognitive task intensities of jobs have increased. During the period of analysis, NRCA and NRCI task content of jobs in India increased by 10 and 9 percentage points respectively (Figure 1). In contrast, manual task instensities, both routine as well as non-routine have declined sharply. The decline in non-routine manual task intensity has been significantly higher than in routine manual task intensity.

Our results further show that RC task intensity of Indian jobs has not declined. In fact, the RC task intensity of Indian jobs has increased by 3.2 percentage points between 1983-84 and 2011-12. However, most of the observed increase in RC task intensity took place before 1998-99. Since 1998-99, the RC task intensity has mostly been constant. A sectoral analysis suggests that RC task content has been surviving because of the services and agriculture sectors, both of which have witnessed an increase in RC task intensity. However, there has been a complete de-routinisation of jobs in the manufacturing sector after 1998. It perhaps shows that the Indian manufacturing sector has gone for rapid automation since 1998 when 100% foreign direct investment was allowed in most manufacturing industries.

Figure 2. Trends in task content of jobs in India

Notably, all birth cohorts have witnessed a similar trend in their task intensities. We also see that changes in task intensities are not solely driven by sectoral shift in employment. Changes in the two non-routine cognitive task contents are strongly associated with changes in total factor productivity3. All these findings indicate that adoption of technology seems to be a major factor behind the evolution of non-routine cognitive tasks in India.

Implications for education and skilling

The changing task content of jobs in India has significant implications for education and skilling. While the demand for cognitive skills has increased, the supply of these skills seems to be lacking behind. The latest Talent Shortage Survey corroborates this and shows that 56% of employers in India face difficulties in filling job vacancies due to skill and talent shortage (Manpower Group, 2018). If not addressed urgently, skill shortage can be fatal for economic growth.

Fortunately, the Government of India has realised the growing role of skills and therefore has started an ambitious skilling programme under the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY). With this scheme, the government aims to provide soft skills and other industry-relevant skills to 10 million youths. The government has also notified the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme to provide apprenticeship training to 5 million youth by 2019-20. Although these are steps in the right direction, they are not directed towards cognitive skills formation and hence, cannot be a substitute for good quality, formal education.

The government had to introduce the short-term skilling programme because the formal education system in India has failed miserably at all levels. Employers in India frequently argue that youth, even with graduate degrees, are not employable. Since the demand for cognitive skills is expected to increase further in the years to come, the government should focus more on the quality of education, particularly schooling, to address the issue of growing skill shortage. Focus on school education is also required to avoid the adverse distributional consequences of technology inducing changes in the task content of jobs. India has a very inefficient, and dualistic education system. It has some very good private schools where the quality of education is comparable to global standards. However, access to these schools is primarily restricted to the economically well-off section of the society. In contrast, a large section of Indian society still relies on government schools for the education of their children. It is widely documented that government-run schools are in disarray and fail miserably to impart basic reading and computational skills to their students. A recent survey by the Delhi government’s Directorate of Education shows that 74% of grade 6 students in Delhi government-run schools cannot read a paragraph in Hindi, the native language, while 67% of students cannot perform simple 3 digits by one digit division. Given this stark difference in the quality of education between government and private schools, the changing nature of jobs can further exacerbate the existing economic inequality. Therefore, there is a burning need to fix the government-run schools.

Notes:

- The O-NET database, collected by the US Department of Labour, contains a rich set of variables that describe work and worker characteristics, including skill requirements of different occupations. Various task intensities in O-Net data have been measured on a scale of 1 to 5.

- Our dataset contains around 2 million observations.

- Total factor productivity is a measure of efficiency of the inputs used in a production process.

Further Reading

- Autor, David A, Frank Levy and Richard J Murnane (2003): “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4). Available here.

- Acemoglu, D and D Autor (2011), ‘Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings’, in Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4.

- Manpower Group (2018), ‘ Solving the Talent Shortage: Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge’, Manpower Group.

- Michaels, Guy, Ashwini Natraj and John Van Reenen (2014), “Has ICT polarized skill demand? Evidence from eleven countries over twenty five years”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1): 60-77.

- Rifkin, J (1995), The End of Work - The Decline of the Global Labour Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era, Tarcher/Putnam, New York, 1995.

- Vashisht, P and J Dubey (2018), ‘Changing Task Content of Jobs in India: Implications and Way Forward’, ICRIER Working Paper No. 355, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, New Delhi.

- Vivarelli, M (2012), ‘Innovation Employment and Skills in Advanced and Developing Countries: A Survey of Literature’, IZA Discussion Paper 6291, Institute for the Studies of Labour (IZA).

13 February, 2019

13 February, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.