In 2017, mandated paid maternity leave for women employees in India was increased from 12 weeks to 26 weeks. Analysing data for 160,000 households, this article finds that the policy change caused a fall in employment and income among women in the high-fertility age group. This was driven by a rise in firms’ ‘reservation productivity’ for hiring these women, since employers alone finance the leave.

Motherhood, or the possibility of motherhood, is a natural and fundamental reality facing young women (and their employers). Low female labour force participation, gender wage gap, and slower career progression of women compared to their male counterparts has often been attributed to maternity – this is also known as the ‘motherhood penalty’. Mandated maternity leave (ML) policies are well-intentioned federal policies that seek to eliminate, or at least reduce, the motherhood penalty faced by young women in the fertile age group1 Studies have found mixed evidence on the labour market effects of ML policies in the context of advanced western economies (Olivetti and Petrongolo 2017). While ML policy in India can be traced back to the early 1960s, it was amended in 2017 by extending the duration of ML. In our study (Banerjee, Biswas and Mazumder 2022), we examine the effect of this ML expansion on women’s labour market outcomes in the country.

Maternity leave policy in India

India had an ML policy in place much before many of the advanced economies. The Maternity Benefit Act of 1961 entitled women employed in the formal sector to 12 weeks of ML. Moreover, ML in India has been designed to protect pay during the leave period. The pay during the ML period is calculated as the average wage during the three months preceding absence on account of childbirth. Notably, it is the employer that bears the entire wage cost of female employees availing ML.

During the last decade, the Government of India amended the existing ML policy. The Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act was enacted in 2017 with a view to improving labour market outcomes for mothers and post-natal care of newborns and infants. As per the new policy, women employed in the formal sector are entitled to 26 weeks of pay protected ML for the first two childbirths. Additionally, organisations were required to set up crèche facilities if they have more than 50 female employees. Again, the entire burden of wages during the extended period of absence from work, along with the costs of setting up crèches, are to be entirely borne by the employers, with no financial support from the government. This is unlike the ML policy design in western economies like Canada, France, and the United States. In these countries, the government and/or insurance companies largely bear the wage costs. Even in other developing economies like Brazil and Vietnam, the government – at least partially – funds wage bills during the period of ML.

The study

To empirically examine the impact of the extension of ML in India, we use the Consumer Pyramids database from the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE). It is a nationally representative household panel dataset covering around 160,000 households, and each household is surveyed thrice a year ( in January, May and September). The survey also provides individual-level information related to gender, age, employment, income, education, caste affiliation, and religion, among others, over the three waves. The structure of the dataset, which measures the same households repeatedly across time, enables us to infer the causal effect of the extension of the duration of ML on female employment and income by exploiting the exogenous policy reform, on the surveyed working age (15-64) individuals. We rely on the fertility trends observed from five National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) rounds (conducted in 1992-93, 1998-99, 2005-06, 2015-16 and 2019-21), and identify women aged 20 to 29 as the high-fertility group. The women in the high-fertility group (‘treatment group’) ex-ante, have the highest probability of being affected by the ML reform. Women who are not in the high-fertility age group and men constitute our ‘control group’. We argue that women who are not in the high-fertility age group are less likely to be affected by the policy as they are either too young to be married and have children, or are more likely to have two or more children already (extended ML is only applicable for the first two childbirths). All men, by definition, are not directly affected by the ML policy change. Further, given the timing of the amendment, data pertaining to individuals up to Wave 1 of 2017 constitutes our pre-reform period, and Wave 2 of 2017 onwards is the post-reform period.

We use a difference-in-differences (DD) estimation strategy to gauge the labour market impacts of the reform. This estimation strategy compares the difference in outcomes between the two groups – the women in the high fertility group and others – over time in the pre- and post-reform periods. The obtained estimate gives the causal effect of the reform on women’s labour market outcomes after controlling for individual and household factors.

Findings

Our empirical analysis indicates an adverse effect of the expansion of ML in India on women’s labour market outcomes. Our estimates suggest an over 30 percentage point fall in women’s employment in the post-reform period. The results indicate that extension of ML, which increased the cost of hiring a female worker, may reduce the likelihood of firms hiring women belonging to the high-fertility age group. This is so since the firms may attach a non-zero probability of a female worker in the high-fertility group availing ML post joining work, whereas the probability is zero for the control group. Given that the burden of wage costs during ML is entirely borne by the firms, it is rational for the employers to reduce hiring of females in the specific age bracket. Furthermore, we also document a fall in income in the range of 2- 4% for employed women on account of the extension of the ML. The fall in income is likely driven by firms paying lower wages to employed women belonging to the high-fertility group in the post-reform period: the ‘cost’ of hiring women in this age group increased, and firms responded by lowering the ‘average’ wages offered to women in this group.

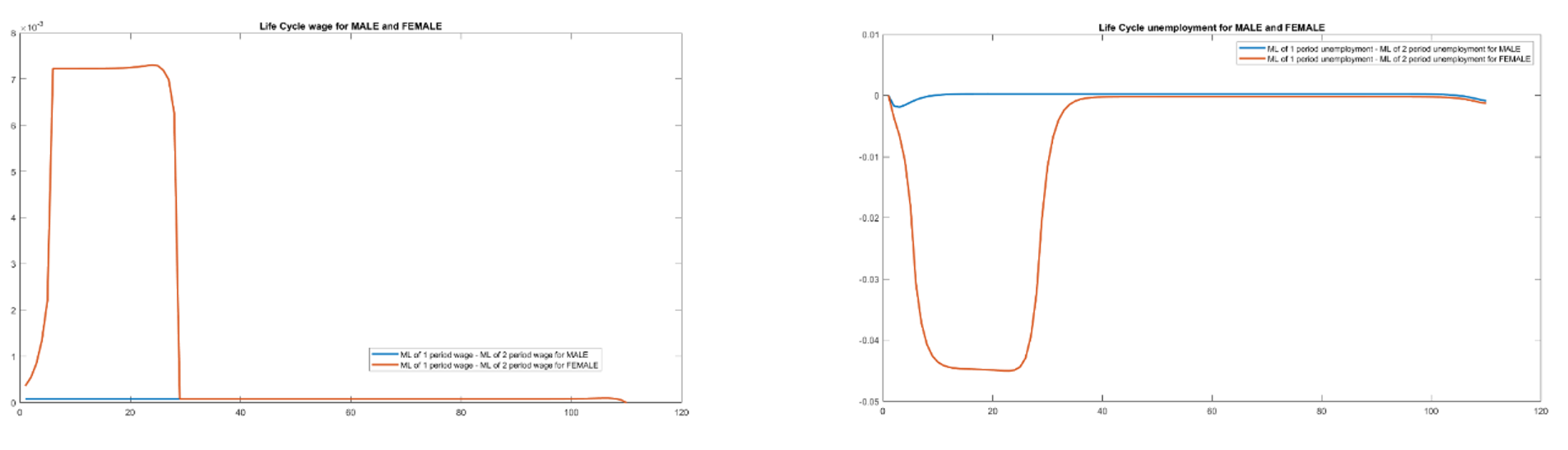

Based on the framework proposed by Chéron et al. (2013), we also propose a life-cycle model of search and matching frictions to explain our findings. The model considers two types of employees – female and male workers, wherein the female workers in the high-fertility age-group face the possibility of pregnancy (we call that a ‘maternity event’) , while the other workers do not. Additionally, the ML policy asserts that, given a maternity event, the firm where the female worker is employed has to offer paid leave. Our simulation results show that an increase in the ML policy (of the nature described above) may result in worsening of wage rate and unemployment rate for women in the high-fertility age group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differences in wage rates (left panel) and unemployment rates (right panel)

Note: The vertical axes gives the difference in wage rates (left panel) and unemployment rates (right panel), in normalised per period rates. The horizontal axis gives the age (in years) of the workers.

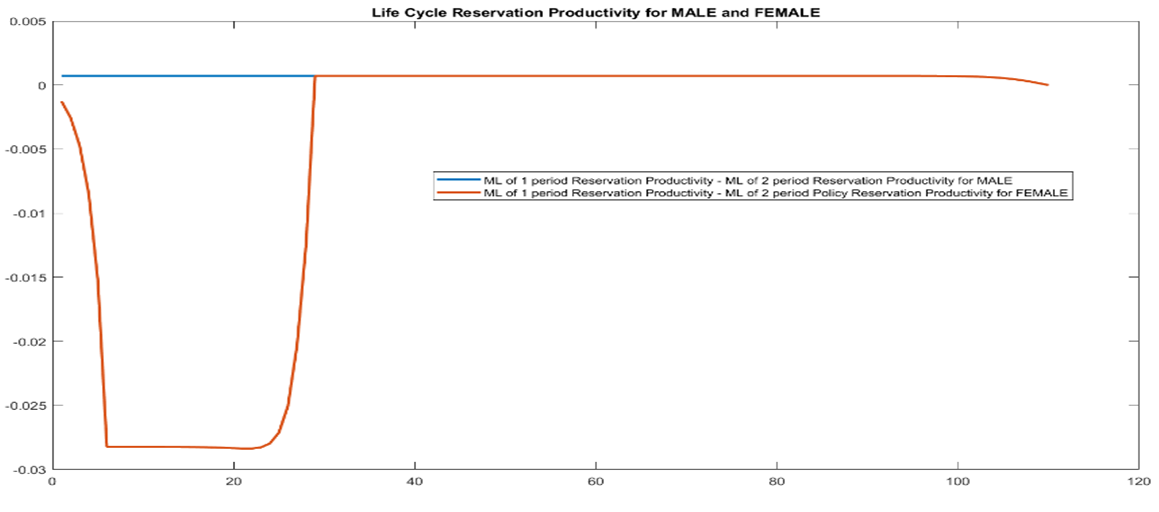

The distortionary ML policy may exacerbate the pre-existing gender gap in unemployment and wages owing to increase in the ‘reservation productivity’2 of the firms for women in the high-fertility age group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences in the reservation productivity

Notes: (i) The vertical axis gives the difference in reservation productivity, where zero denotes no difference and negative values indicate that the reservation productivity of workers increased in the period post ML expansion compared to the pre-ML expansion period. (ii) The horizontal axis gives the age (in years) of the workers.

Concluding remarks

Maternity leave policies have the potential to reduce the motherhood penalty faced by women in the labour market. However, correct policy design is critical to ensure that such women-centric policies benefit the targeted group. In India, the financing of maternity benefits remains the responsibility of the employer. The costs of hiring women workers, especially those belonging to the high-fertility age group, further increased after the ML policy was amended in 2017. Firms have responded by increasing the reservation productivity of women workers in the high-fertility age group, resulting in a fall in their employment and wages in the period after the reform. The adverse labour market effects observed for high-fertility women in India following the expansion of the ML, even though undesirable and unintended, are not very surprising. The findings call for complementary policies to reduce the cost burden of maternity benefits faced by formal establishments in India, so that well-intentioned and necessary welfare policies do not end up exacerbating the problems they aim to solve.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Reserve Bank of India.

Notes:

- In India, the fertility rate peaks in the age group of 20-29 years, as per data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)

- Reservation productivity is the minimum productivity at which a firm is willing to hire a worker. A higher reservation productivity implies stricter entry requirements for workers.

Further Reading

- Olivetti, Claudia and Barbara Petrongolo (2017), “The Economic Consequences of Family Policies: Lessons from a Century of Legislation in High-Income Countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1): 205-230.

- Banerjee, P, S Biswas and D Mazumder (2022), ‘Maternity Leave and Labour Market Outcomes’, Working Paper, SSRN 4159552.

- Chéron, Arnaud, Jean-Olivier Hairault and François Langot (2013), “Life-cycle Equilibrium Unemployment”, Journal of Labor Economics, 31(4): 843-882.

04 March, 2024

04 March, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.