In several Indian states, a large proportion of child births continue to be delivered at home, and institutional deliveries in both public and private health facilities lead to high out-of-pocket expenditures. Analysing National Family Health Survey data, Prem Shankar Mishra and TS Syamala examine the trends in institutional deliveries over the years, as well as disparities across rural and urban areas and among marginalised groups.

Maternal and child healthcare services in India – including antenatal care, natal care (institutional delivery, or births delivered in a medical facility), postnatal care, and childcare – are meant to be free of cost in public health facilities. Several policies and programmes have been designed to promote and support the provision of these services. For example, Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)1 and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK)2 encourage institutional delivery with the objective of reducing maternal and infant deaths. Due to the implementation of these programmes, institutional delivery in India has increased many folds (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF International, 2017). However, the 2019-20 NFHS (National Family Health Survey)-53 report shows that in several states the proportion of institutional deliveries continues to be below the national average, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure for institutional deliveries in public facilities is high, and the rate of c-section (caesarean) deliveries is much greater than the national average (IIPS, 2020) and as compared to the ideal international rate (World Health Organization (WHO), 2015).

In this post, we analyse data from two rounds of the NFHS (NFHS-5 in 2019-20, and NFHS-4 in 2015-16)4, to understand the trends in institutional deliveries, related OOP expenditures, and c-section deliveries – across rural and urban areas of the major Indian states and union territories (UTs).

Institutional deliveries have increased – albeit unevenly across the country

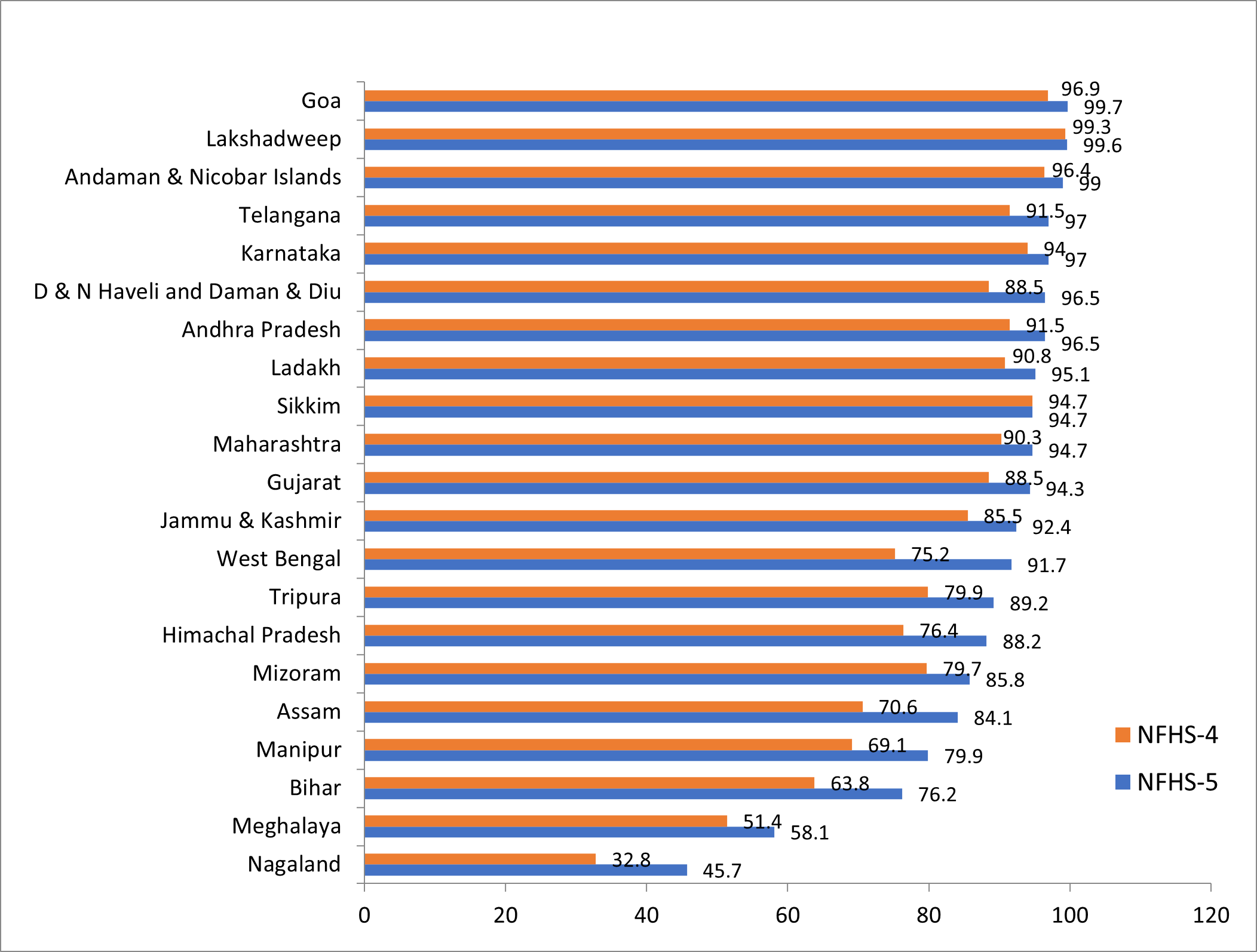

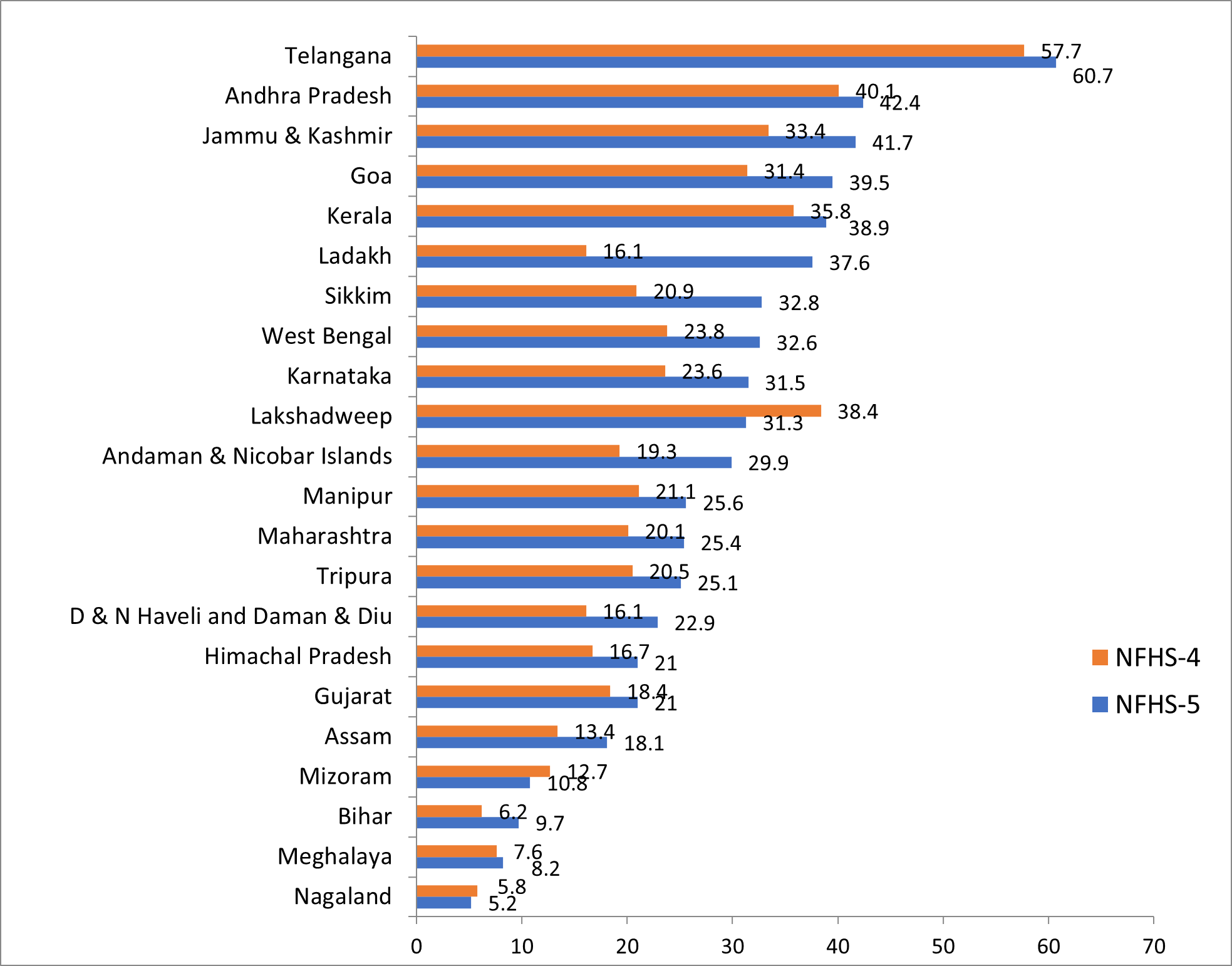

Overall, institutional deliveries have increased from 39% in 2005-06 to 79% in 2015-16, and further to 89% in 2019-205. Yet, there are large variations across states/UTs. For instance, Goa, Telangana, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, and West Bengal have institutional delivery rates that are higher than 90%. On the other hand, states such as Nagaland, Meghalaya, Bihar, Manipur, and Assam have low institutional delivery rates.

Studies in many of the states have shown that cost is a major barrier in opting for an institutional delivery (Garg and Karan 2009, Mohanty and Kastor 2017, Mishra and Mohanty 2019). Women have to spend money for deliveries, even in public health facilities.

Figure 1. Institutional deliveries (public and private), across major states/UTs, 2015-16 and 2019-20

The JSY programme aims to reduce OOP expenditures that families incur during childbirth, and promote institutional delivery at public health facilities. The target beneficiaries include all Scheduled Caste/Tribe (SC/ST) women, and those living below the poverty line, who are 19 years of age or above at the time of delivery. The financial support that JSY offers pregnant women has led to an increase in institutional delivery rates among marginalised communities, particularly SC/STs (Mishra et al. 2021a, IIPS, 2020). Data indicate that JSY attained 36.4% coverage across rural and urban areas between 2005-06 and 2015-16, with the figure being 44.3% for SC/STs and 33% for non-SC/STs. However, a recent study by Mishra et al. (2021b) finds huge disparities in the scheme’s coverage between EAG (Empowered Action Group)6 (57.3%) and non-EAG states (24%).

Rising OOP expenditure for institutional deliveries

India spends 1.2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health, which covers only 25% of the cost of healthcare services, leaving families to bear the remainder on their own (Mishra and Mohanty 2019). This financial burden prevents women from poor and marginalised communities from accessing institutional deliveries.

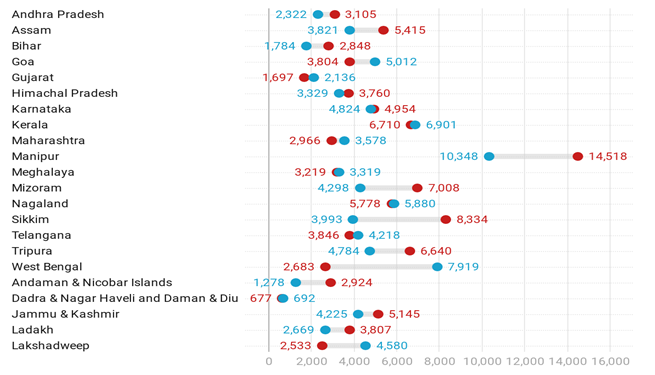

Figure 2. OOP expenditure (in Rs.) on institutional deliveries, 2015-16 and 2019-20

Notes: (i) Blue and red circles denote OOP expenditure in 2015-16 and 2019-20, respectively. (ii) The chart includes states and UTs surveyed in the first phase of NFHS-5.

According to NFHS-5, OOP for institutional deliveries increased from Rs. 4,178 in 2015-16 to Rs. 4,653 in 2019-20. OOP expenditure tends to be higher in Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, West Bengal, and Kerala. This is because most of these states are located in hilly regions and have poor road connectivity and transportation facilities, and lack robust public health infrastructure in the form of ambulance services, laboratories for testing, etc. Further, evidence shows that in India, patients may need to give tips/gratuity in order to get good services at public health facilities (Landrian et al. 2020).

Rural-urban differences

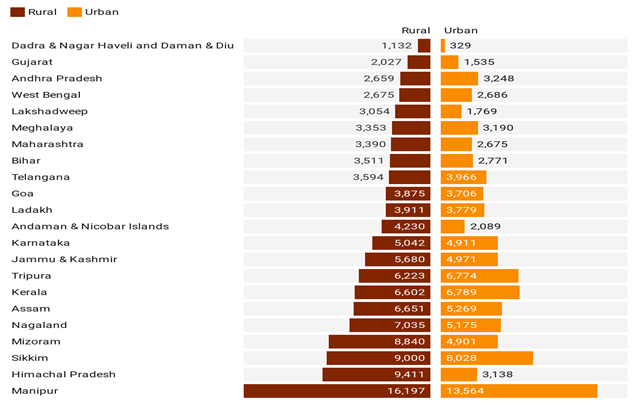

Financial burden due to OOP expenditure is higher among rural households than urban households, with the former spending an average of Rs. 5,368 for a normal delivery in a public facility, as compared to Rs. 4,330 by urban households (as in 2019-20).

A key source of OOP is the steep cost of c-section deliveries, which results in households incurring catastrophically high health expenses. On average, the rates of c-section deliveries (as a proportion of all deliveries) during 2019-20 were 50.1% in rural areas and 54.5% in urban areas in the private sector, and 20.7% in rural and 28.9% in urban areas in the public sector.

Figure 3. Rural-urban difference in OOP expenditure on births delivered in public health facilities, 2019-20

Concerning increase in rates of c-section deliveries

On average, the rates of c-section deliveries have grown across the country, from 17% in 2015-16 to 23.1% in 2019-20, with Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Kerala, and West Bengal topping the chart. This trend poses a public health concern as the recommended rates, as per the international healthcare community, is 10-15% (WHO, 2015). Overall, 53.1% of the c-section deliveries in 2019-20 took place in private facilities – an increase from 42% in 2016. In Sikkim, Assam, Karnataka, and Tripura, over 50% of the c-section deliveries take place in private facilities. However, in a few states, the prevalence of c-sections is still quite low – for instance, in Bihar (3.6%), Nagaland (8%), Meghalaya (9.2%), Mizoram (9.8%), and Assam (15%) – on account of poor health infrastructure and lack of human resources to carry out these procedures.

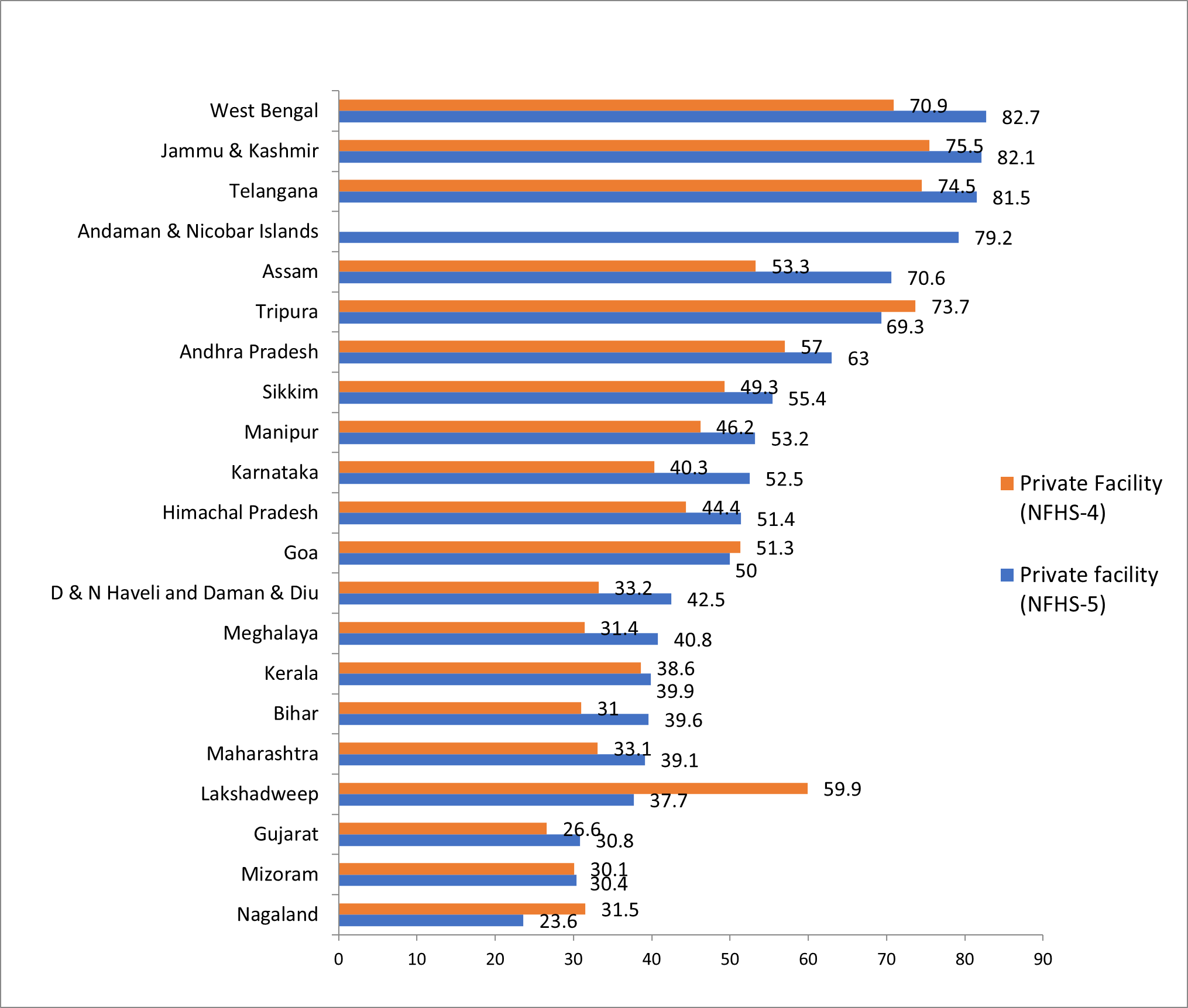

Figure 4. C-section deliveries, 2015-16 and 2019-20

High OOP expenditures associated with c-sections can drive poor and marginalised households into debt and extreme poverty. The high rate of c-section deliveries among women is also known to cause several socioeconomic, psychological, and health problems (Bhatia et al. 2020). A series by the Lancet (2018) pointed out that delivery by c-section is associated with both short- and long-term health effects and healthcare costs. This has led to more severe morbidity and mortality among women and children, vis-à-vis normal deliveries.

This increase in rates of c-section deliveries in the private sector is due to various reasons – not all of which are medical, as women’s characteristics and preferences also matter. However, evidence shows that it is often a physician-induced demand for c-section procedures, as a result of perverse financial incentives in private facilities (Bhatia et al. 2020).

Figure 5. C-section deliveries in private facilities, 2015-16 and 2019-20

Discussion

Inequity in the access to and utilisation of maternal and child healthcare services across different socioeconomic groups in India, is largely due to an escalation in the financial burden of institutional delivery – even in free public health facilities.

The National Health Mission (NHM) envisages universal access to equitable, affordable, and quality healthcare services, which are accountable and responsive to people's needs – especially women and children. Under NHM, the JSY and JSSK programmes have endorsed financial support to women and children in healthcare services in order to reduce related OOP expenditure and improve their health outcomes. However, due to weaknesses in the programme – such as lack of universal coverage, exclusion of women below 19 years of age and those with more than two children, no referral transport benefits, lack of good quality emergency obstetric and comprehensive emergency obstetric care, regional inequality in public health infrastructure and human resources, and lack of equity-based implementation – India has not yet achieved its targets of universal health coverage (Sustainable Development Goal 3). Therefore, strategic implementation and a better designed system of demand-side financing – through programmes such as JSY and JSSK – is important. There is a need to increase JSY coverage among marginalised groups, and mobilise resources and the community health workforce in regions with low coverage. Besides, to enhance the effectiveness of this programme, community health workers should be trained and engaged in diffusing information and increasing awareness, at the individual and household levels.

To reduce c-section deliveries as a whole, especially in the private sector, the government must re-examine the issue and encourage women to receive full antenatal care services to avoid any complications in the later phases of pregnancy. The issue of perverse incentives to carry out unnecessary c-section deliveries in the private sector needs to be addressed as well. This can be through the monitoring of unregulated private-sector providers, physician-induced demand for c-section procedures, and other malpractices that occur in private hospitals.

Improving supply-side mechanisms, through the development of public health infrastructure and human resources, may also enhance accessibility and utilisation of maternal and child health services, and can reduce OOP expenditure and availing of private sector treatment. The government must follow a strategy of checks and balances, by monitoring and evaluating the existing schemes and addressing issues in their functioning, to ensure that the NHM’s goal of equitable, affordable, and quality healthcare services is achieved.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) is a safe motherhood intervention, launched in 2005 under the National Health Mission. It seeks to promote institutional delivery through a conditional cash transfer that incentivises poor pregnant women to deliver their babies in public health facilities.

- Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) is a scheme introduced by Government of India to provide free and cashless services to pregnant women – including normal deliveries and caesarean operations – and sick, newborn babies (up to 30 days after birth) in public health facilities in both rural and urban areas.

- Released for 22 states/union territories (UTs).

- NFHS-5 provides information on population, health, and nutrition in India, for each state/UT. As in the case of NFHS-4, NFHS-5 also provides district-level estimates for several indicators related to key maternal and child healthcare services. We present information for 22 states/UTs, for which data are available.

- As per NFHS-5 factsheets, in states for which data are available.

- Eight socioeconomically backward states – Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh – are referred to as the Empowered Action Group (EAG) states. These lag behind in demographic transition, and have the highest infant mortality rates in India.

Further Reading

- Belizán, Jose et al. (2018), “An approach to identify a minimum and rational proportion of caesarean sections in resource-poor settings: a global network study”, The Lancet Global Health, 6(8): e894-e901.

- Bhatia Mrigesh, Kajori Banerjee, Priyanka Dixit and Laxmi Kant Dwivedi, “Assessment of Variation in Cesarean Delivery Rates Between Public and Private Health Facilities in India From 2005 to 2016”, JAMA Network Open, 3(8): e2015022.

- Bhatia, M, LK Dwivedi, K Banerjee and P Dixit (2020), “An epidemic of avoidable caesarean deliveries in the private sector in India: Is physician-induced demand at play?”, Social Science & Medicine, 265: 113511.

- Garg, Charu C and Anup K Karan (2009), “Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: a disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India”, Health Policy and Planning, 24(2): 116-128. Available here.

- Goli, Srinivas, Anu Rammohan and Moradhvaj (2018), “Out-of-pocket expenditure on maternity care for hospital births in Uttar Pradesh, India”, Health Economics Review, 8(5): 1-16. Available here.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF International (2017), ‘National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16’, Report.

- International Institute of Population Sciences (2020), ‘State-level Fact Sheets on NFHS-5 2019-20’.

- Issac, Anns, Chatterjee, Susmita, Srivastava, Aradhana and Sanghita Bhattacharyya (2016), “Out of pocket expenditure to deliver at public health facilities in India: a cross sectional analysis”, Reproductive Health, 13(99).

- Landrian, Amanda, Beth S Phillips, Shreya Singhal, Shambhavi Mishra, Fnu Kajal and May Sudhinaraset (2020), “Do you need to pay for quality care? Associations between bribes and out-of-pocket expenditures on quality of care during childbirth in India”, Health policy and planning, 35(5): 600-608. Available here.

- Mahajan, Niharika and Baljit Kaur (2021), “Analysing the expenditure on childbearing: a community-based cross-sectional study in rural areas of Punjab (India)”, BMC Health Services Research, 21(76).

- Mishra, Prem Shankar, Pradeep Kumar and Shobhit Srivastava (2021a), “Regional inequality in the Janani Suraksha Yojana coverage in India: a geo-spatial analysis”, International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1): 1-14. Available <sptarget="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer"an style="font-weight: 400;">here.

- Mishra, Prem Shankar, Karthick Veerapandian and Prashant Kumar Choudhary (2021b), “Impact of socio-economic inequity in access to maternal health benefits in India: Evidence from Janani Suraksha Yojana using NFHS data”, PLoS ONE, 16(3): e0247935. Available here.

- Mishra, Suyash and Sanjay K Mohanty (2019), “Out-of-pocket expenditure and distress financing on institutional delivery in India”, International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1): 1-15.

- Mohanty, Sanjay K and Anshul Kastor (2017), “Out-of-pocket expenditure and catastrophic health spending on maternal care in public and private health centres in India: a comparative study of pre- and post-national health mission period”, Health Economics Review, 7(1): 31. Available here.

- Sandall, Jane et al. (2018), “Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children”, The Lancet, 392(10155): 1349-1357.

- World Health Organization (2015), ‘WHO statement on caesarean section rates’, Executive Summary.

30 July, 2021

30 July, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.