In the first of two articles about women’s fertility and family planning, Anukriti et al. discuss the influence that mothers-in-law have on women’s access to family planning services, with them on average preferring more children and sons than the women and their husbands. They describe the effects of an intervention that provides access to subsidised family planning to women in Uttar Pradesh. The intervention increased conversations about family planning between women and their mothers-in-law, with a consequent increase in mothers-in-law’s approval of family planning, and significantly, an increase in daughters-in-law’s clinic visits.

Mothers-in-law, especially those in South Asian households, can exert significant influence over other women. In settings where women move into their husbands’ (often extended or joint) households following marriage, a woman’s mother-in-law – the likely matriarch of the household – plays a crucial role in determining her mobility, access to services and resources outside the home, and overall wellbeing. Indeed, relationships between mothers-in-law and their daughters-in-law in extended households in rural India are not always balanced, as young daughters-in-law typically lack the power to assert and act on their own preferences within this household structure. Arguably, a woman’s mother-in-law may be an even stronger influence on a woman than her husband, especially during the early years of an arranged marriage.

In a recent paper (Anukriti et al. 2022), we study the interactions between mothers-in-law and their daughters-in-law in the context of fertility and family planning. Specifically, our sample comprises of 671 married women, aged 18-30, from 28 villages in the Jaunpur district of Uttar Pradesh. We conducted a baseline survey in 2018, which revealed that women lack the freedom to access health facilities alone and have limited say in decision-making about healthcare for themselves. They have a substantial unmet need for family planning, as reflected in the fact that even though almost half our sample did not want to have another child, only one-fifth of women were using modern contraception, and only a third had ever visited a clinic for family planning services.

The implications of misalignment in fertility preferences

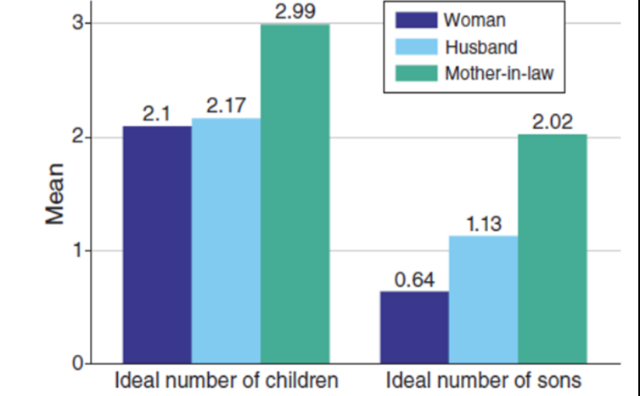

There is significant mismatch between women and their mothers-in-law, in terms of the ideal number of children and sons they prefer. Most women in our sample (78%) live with their mothers-in-law, but half of them report never having discussed family planning with them. Moreover, 42% of the women believe that their mothers-in-law do not approve of family planning, and 72% believe that their mothers-in-law want them to have more children than they want to have. An average mother-in-law wants her daughter-in-law to have one more child and 1.4 more sons than the daughter-in-law wants to have (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Misalignment in fertility preferences within households

Source: Anukriti et al. 2022

Note: This figure shows the baseline average ideal number of children and sons for women, their husbands, and their mothers-in-law, all as reported by the sample women.

In comparison, discordance in fertility preferences between a woman and her husband is small. Almost 89% of women report that their husbands approve of family planning. An average husband wants his wife to have 0.07 additional children and 0.49 more sons than his wife wants to have.

The misalignment of fertility preferences between the daughter-in-law and her mother-in-law has negative implications for the daughter-in-law. When daughters-in-law have low intra-household bargaining power relative to the mother-in-law, their preferences over their contraceptive access and use may receive less weight in household decision-making. Moreover, mothers-in-law may curtail their daughters-in-law’s access to social connections outside the home if they fear that outside influence is causing the daughter-in-law’s fertility outcomes and family planning use to deviate from the mother-in-law’s preferences (Anukriti et al. 2020).

Subsidised family planning as a potential solution

Offering women vouchers for subsidised family planning services can improve communication about family planning with their mothers-in-law. In our study, we offered a randomly selected subset of women access to subsidised family planning services at a local clinic in Jaunpur, while the remaining women were assigned to a control group that did not receive the voucher. Voucher recipients were 45% more likely than the control group to have initiated discussions about family planning with their mother-in-law.

Voucher recipients also experienced an increase in their mothers-in-law’s approval of family planning. Women in the treatment group reported an 11% increase in their perception of their mother-in-law’s approval of family planning relative to the control group. In comparison, there was no impact of the voucher on husbands’ approval of family planning as perceived by the wife. A potential reason for this effect is that the vouchers enabled treated women an opportunity to discuss family planning more easily with their mothers-in-law. Moreover, our intervention significantly increased the likelihood of treated women visiting a clinic for family planning services by 77%, suggesting that the improvement in their mother-in-law’s approval is potentially a relevant mechanism for the success of vouchers in increasing access to family planning.

Conclusion

Family structures and co-residence patterns are key determinants of women’s economic decision-making. Ignoring these features of the household can lead to policies and programmes that are ineffective and potentially even harmful to recipients. Policies that seek to improve women’s wellbeing in contexts where patrilocal, extended families are common, should take into account the central role of mothers-in-law within the household to increase their effectiveness. Mothers-in-law can act as gatekeepers and prevent their daughters-in-law from accessing essential services such as family planning, which in turn can have adverse impacts on women’s health and wellbeing. Future policies should address this potential misalignment of fertility preferences, and asymmetry of information and bargaining power between the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law in a manner similar to the family planning interventions that have aimed to challenge the intrahousehold allocation issues between husbands and wives (for example, through Husbands’ Schools and Future Husbands’ Clubs).

Nearly 86% of women at baseline reported that they would be more likely to go to a health facility for family planning services if a friend or a relative volunteered to come with them. Can women’s peers be leveraged to improve agency curtailed by family structures? The second blog (‘Bring a friend: Leveraging financial and peer support to improve women’s reproductive agency’) explores this question further and can be read here.

Further Reading

- S Anukriti, Catalina Herrera-Almanza, Mahesh Karra, and Rocío Valdebenito (2022), “Convincing the Mummy-ji: Improving Mother-in-Law Approval of Family Planning in India”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 112: 568-572. Available here.

- S Anukriti, Catalina Herrera-Almanza, Praveen K Pathak and Mahesh Karra (2020), “Curse of the Mummy‐ji: The Influence of Mothers‐in‐Law on Women in India”, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 102(5): 1328-1351. Available here.

18 August, 2023

18 August, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.